12 Changes That Redefined Lift-Served Skiing in 2022

Pass shuffles, resort sales, name-changes, record skier visits, a building boom, and more.

I’m sure that the majority of you consume The Storm Skiing Journal by printing out each issue, applying a three-hole punch, and tucking it into a binder, indexed and arranged in chronological order. You then tote this around, chuckling over its contents at luncheons and reciting its wisdom to your children at bedtime. If you’re not in this habit, The Storm is now archived at most public libraries across U.S. America.

None of that is true, but pretty much everything below is. The world of lift-served skiing that this newsletter (and associated podcast), obsesses over is changing fast. And while I report on and analyze this landscape every single day (Twitter supercharges the news cycle, and if you don’t follow me there, you should, since I often break news there before I analyze it in detail here), I appreciate that not everyone has time to read every 5,000-word newsletter. Especially when I am delivering more than 100 of them each calendar year.

So, for those of you who appreciate the abridged version, or if you’re new to Storm Nation, here’s a recap of a dozen changes that helped redefine U.S. American lift-served skiing in 2022*.

*Note to You-Forgot Bro: this is not meant to be an exhaustive or definitive list. It is just a conversation starter. Skiing is fun. You are not. Stop bothering me and go find some snow.

1) The megapass landscape continued to evolve

The U.S.-based mega-ski pass has been redefining our ski seasons for years: Epic debuted in 2008, Mountain Collective in 2012, Ikon in 2018, Indy in 2019. Each entered this year with sizeable coalitions. But 2022 is the year the lid blew off this particular supervolcano. Indy added 27 new downhill ski areas. Ikon stacked seven more onto a roster that is already the world’s best. Mountain Collective – moribund when Ikon debuted – dropped five more partners onto its lineup, giving the 10-year-old pass its largest coalition ever. Vail’s Epic Pass and Mountain Capital Partners’ Power Pass each added one new partner, and the reciprocal Freedom Pass and Powder Alliance added seven and five new ski areas, respectively. That’s 53 new ski areas total (though there is some overlap between Ikon and Mountain Collective, which both added Snowbasin and Sun Valley). Here’s a breakdown of which passes added which mountains, in chronological order:

Read full breakdowns of each of these additions below:

Ikon Pass (7)

Mountain Collective (5)

Epic Pass (1)

Andermatt-Sedrun (3/28)

Indy (27)

Sunlight (2/15)

Bluewood, Kelly Canyon, Sawmill (4/27)

Nub’s Nob, Marquette Mountain, Treetops, Mount Kato, Big Rock (6/21)

Black Mountain of Maine, Meadowlark, Aomori Springs (7/19)

Mt. Hood Meadows (7/26)

Mountain High, Dodge Ridge (8/26)

Snowriver, Chestnut, Bluebird Backcountry (9/6)

Calabogie Peaks, Loch Lomond, Mt. Crescent, Arctic Valley (10/11)

Echo Mountain, Granby Ranch (11/15)

Tussey, Peek’N Peak (11/29)

Power Pass (1)

Willamette Pass (10/4)

Powder Alliance (5)

Freedom Pass (7)

Bogus Basin, Little Switzerland, Nordic Mountain, The Rock Snowpark (3/10)

Eaglecrest, Mt. Spokane (8/9)

Cazenovia Ski Club (12/19)

Many passes also lost members: Sun Valley and Snowbasin fled Epic for Ikon and Mountain Collective (both ski areas, which are jointly owned, were previously members of the latter pass); Indy Pass lost Marmot Basin to Mountain Collective; and Alterra pulled its last three owned ski areas – Mammoth, Palisades Tahoe, and Sugarbush – off the Mountain Collective. Telluride, notably, renewed its partnership with Vail and the Epic Pass, foiling the widely predicted Alterra pirating of Vail’s last non-owned U.S. Epic Pass partner (Arapahoe Basin also left Epic for Ikon and Mountain Collective, in 2019). Still, defections remain rare - the Epic Pass was the only coalition to lose more ski areas than it gained, and even that’s not technically true, since Seven Springs, Laurel, and Hidden Valley – which Vail purchased at the end of 2021 – officially joined the Epic Pass for the 2022-23 ski season.

These passes no doubt contributed to the record skier visits that U.S. ski areas logged for the 2021-22 ski season, and select coalitions have aggressively adjusted access to manage day-to-day volume and preserve the ski experience. No pass has evolved as continuously and aggressively as the Ikon Pass. This year, Alterra reduced Crystal Mountain access on the full Ikon Pass from unlimited to seven days, and slid its Washington monster onto its own pass – for $1,699. Alta and Deer Valley also fled the Ikon Base Pass and joined Aspen and Jackson Hole on the Ikon Base Plus Pass, which cost an additional $200.

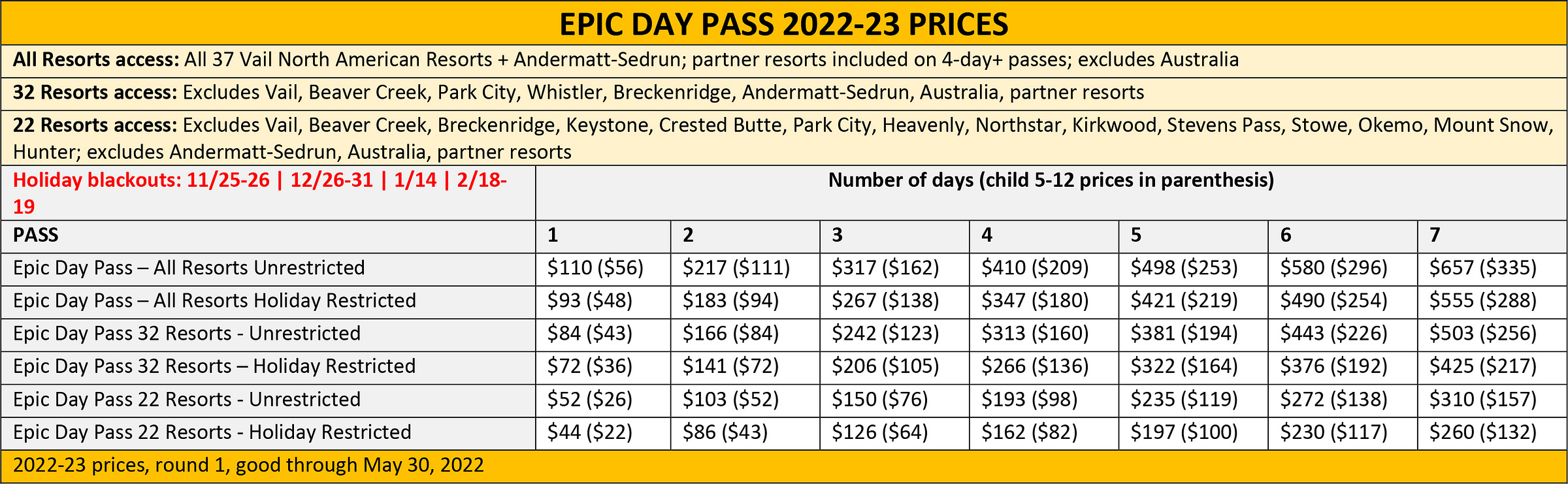

While Vail kept Epic Pass access identical to the previous season, the company introduced a third, ultra-discount tier to its phenomenal Epic Day Pass product, which skiers could use to access Vail’s ski areas in the Midwest, Pennsylvania, and – for some reason – New Hampshire for just $52 ($26 for kids). The seven-day pass ran $310 - $44 per day. Here was Epic Day’s early-bird price grid:

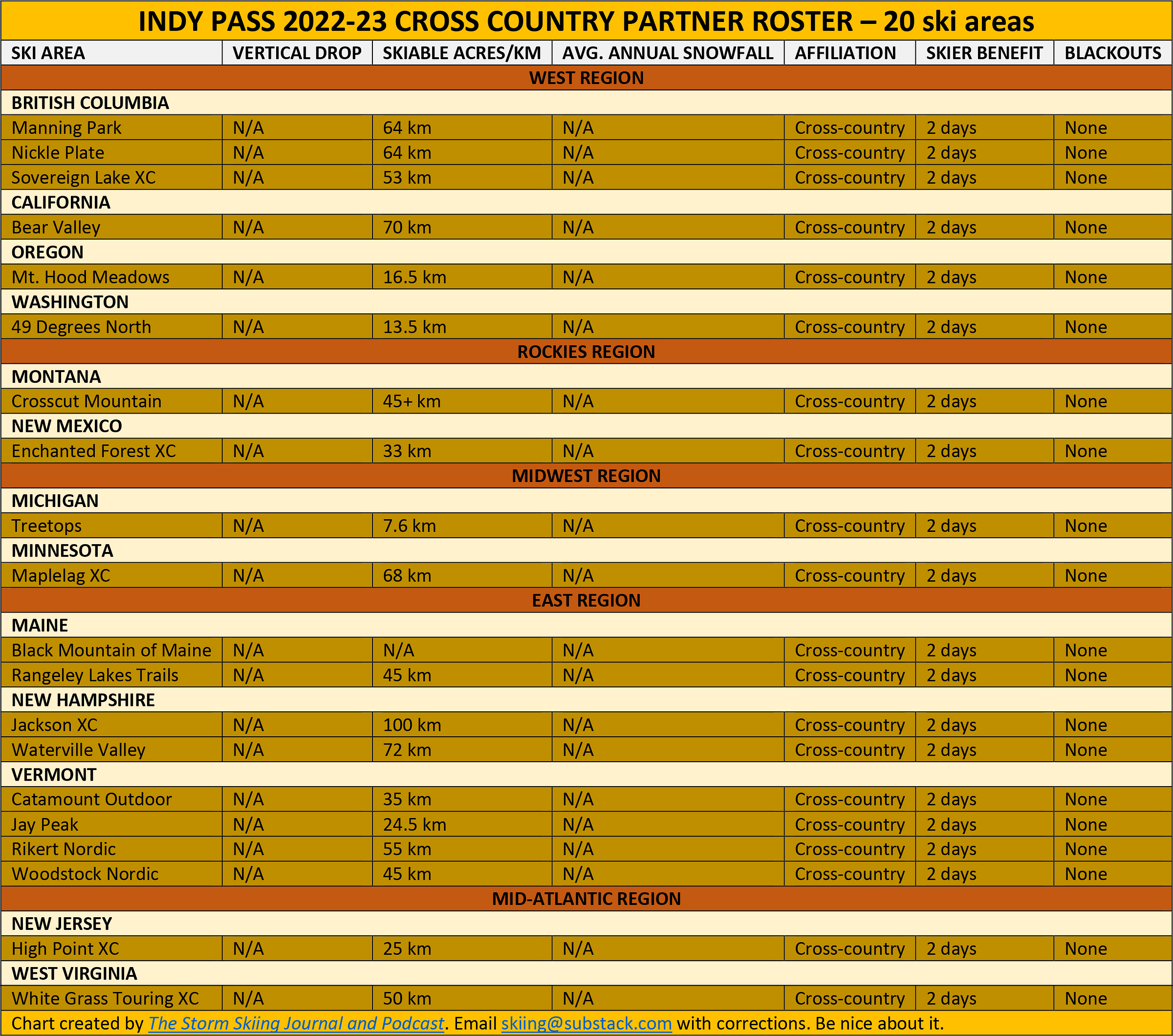

Indy, meanwhile, rolled out two potentially revolutionary products that give nearly any ski area on the planet a conduit into megapass participation: its XC Pass and its discount Allied Resorts program. The XC Pass is just $69 ($29 for kids), and includes two days each at 20 cross-country ski areas (all Indy Passes also include this XC access). Here’s the year-one list:

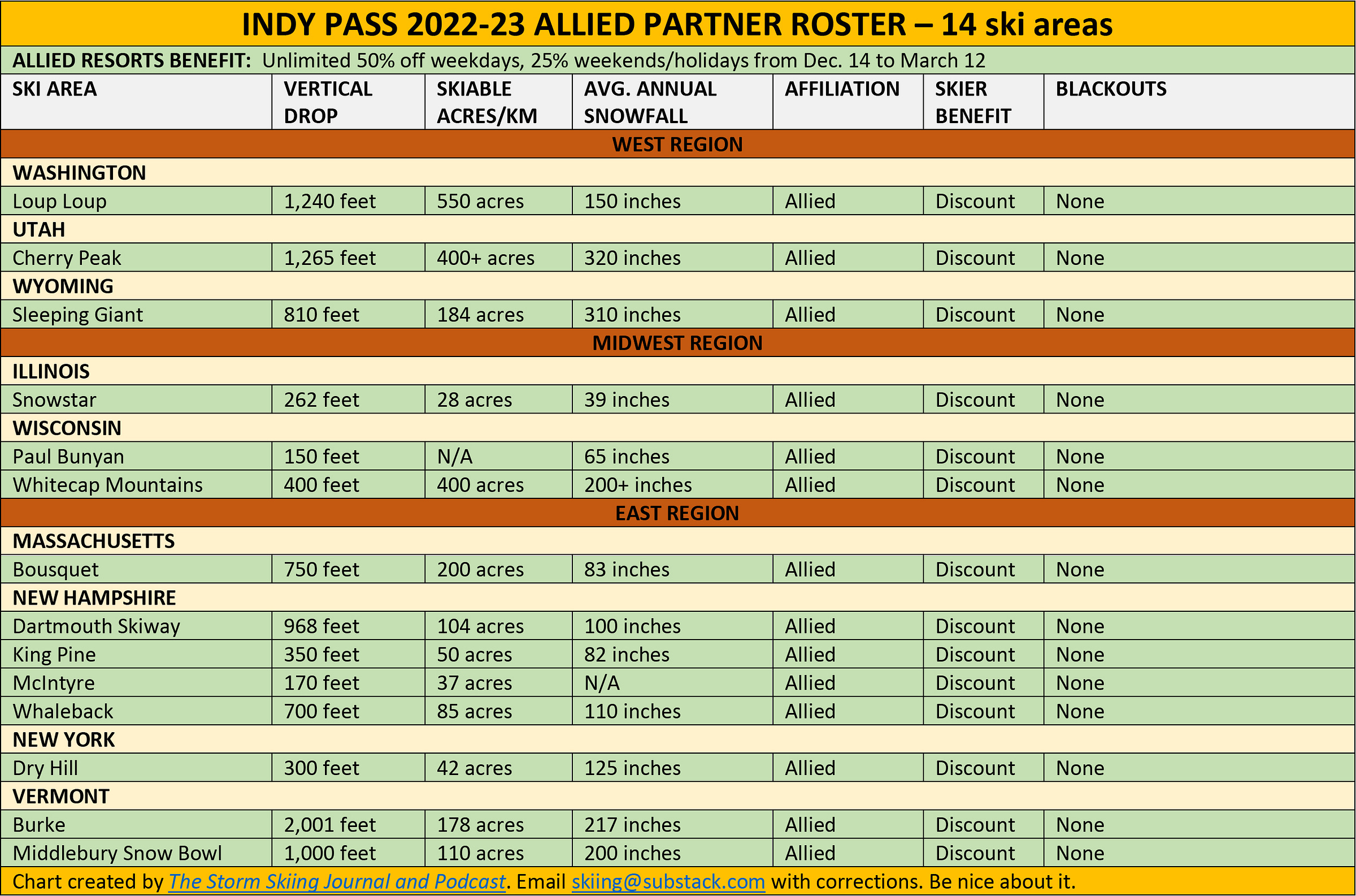

The Allied program gives passholders unlimited discount days at participating areas: half off on non-holiday weekdays, and 25 percent off the remainder of the time. The roster is fairly limited at the moment, but it gives indie ski areas in already-dense Indy regions such as New England a way to participate – and give their passholders access to the discount Indy AddOn pass that full partner resorts can offer. Here’s the 14 inaugural Allied resorts:

These many and varied pass options have so far failed to kill the reciprocal lift-ticket deal. Ski Cooper’s season pass – which debuted in the spring at just $329 – delivers three days each at 65 ski areas. The Freedom Pass and Powder Alliance coalitions are made up of 20 and 21 ski areas, respectively, and deliver three days of access to season passholders of any partner mountain (usually for free). Both continue to grow, as noted above. Still, there are reasons to question the long-term appeal of such arrangements given the growing popularity of the pay-per-visit model that Indy and Mountain Collective have built their respective empires on. Utah giant Powder Mountain dropped all of its reciprocal partnerships after one year on Indy, and Saddleback broke up with Ski Cooper the day after announcing their partnership – the Maine ski area had not realized that Cooper’s pass essentially acted as a competitor to Saddleback’s longtime partner, Indy Pass. In October, Brundage General Manager Ken Rider told me on The Storm Skiing Podcast that he planned to eventually end most – or possibly all – of the more than a dozen reciprocal partnerships the ski area had entered over the years.

2) Morons try to ruin Gunstock

There are two reasons why someone would want to run a ski area: either they really, really love it, or someone is paying them a hell of a lot of money to do it. Neither was true last summer, when a couple of morons who knew nothing about running a ski area and earned $25 per day as appointed commissioners seized control of Gunstock, the Belknap County, New Hampshire-owned mountain that had operated without interruption since 1937.

The fiasco, in brief: On July 20, Gunstock GM Tom Day, a 40-year ski industry vet who earned $175,000 per year (plus bonuses) to run the ski area, stood up at the Gunstock Area Commission’s monthly meeting and resigned following months of interference by commissioners Peter Ness and David Strang. “It seems there’s a lot more control that wants to come from your side of it, so I feel that my role here is diminished,” he said. His senior management team also resigned, and they all walked out. Raucous public meetings followed, and the Belknap County Delegation – the state representatives that appoint and oversee the five members of the Gunstock Area Commission – eventually replaced the controversial commissioners and re-instated Day and his team.

I summarized most of the ordeal in this timeline, and the end of it here. More here. The ski area opened on time, and most people are back to not paying attention to this mid-sized New Hampshire mountain. But this whole misadventure exposed the risk of public ski area ownership, and demonstrated what can happen when individuals obsessed with ideology try to cram something as complex as a modern ski resort into a black-and-white political framework. The one sure fix here would be to sell or lease the ski area, an idea so politically toxic that 17 of the 18 Belknap County Delegation members (all Republicans, by the way), signed a pledge not to even consider the notion.

3) Vail struggles with just about everything, even as 2.3 million things go right

Vail Resorts made a lot of the wrong kind of headlines in 2022. My first Storm Skiing Journal article of the year detailed the company’s struggles to fully open or staff many of its resorts, particularly in the Midwest, in New Hampshire, and at Stevens Pass. The skier experience was compromised enough that Epic and Epic Local Pass sales plunged 12 percent for 2022-23, after rising nonstop for their entire existence. In August, the company had to delay its Bergman Bowl expansion at Keystone – and the new six-pack that was to serve it – to 2023 after a construction crew trenched an illegal access road into the high alpine. Several additional lifts – including two crucial machines at Whistler – hit supply-chain delays.

Meanwhile, the Town of Vail shut down a pre-approved housing project that would have planted 165 beds of affordable worker housing on land Vail Resorts owned. A month later, four idiots in Park City stalled two replacement lifts – a six-pack and an eight-pack – that would have relieved pinch points at America’s largest ski area (Vail sent them to Whistler instead, for 2023 installation, a fact that I find appropriate and hilarious).

There are perhaps more culprits than problems here: Vail’s decision not to invest in labor, a 2021-22 worker vaccine mandate, a lack of appreciation for the primacy of snowmaking in the East, supply-chain issues, bad relations with locals, too-rapid growth, the winter Covid surge, and on and on.

Not everything went wrong, of course: even with all the bad publicity and multiplying fiascos, Vail Resorts still sold 2.3 million 2022-23 Epic Passes, a record.

4) Vail fixes it

Vail did eventually own its 2021-22 operational struggles. In March, the company announced a basket of worker investments that included a $20-an-hour frontline minimum wage and significant investments in housing. In August, the company said that it would limit lift ticket sales at every resort on every day of the ski season. Less-popular crowd-control measures – such as paid parking at Stowe and Park City – followed.

Will it be enough? Probably. While no ski area will ever run perfectly all the time, the sorts of serial, foundational issues that upended Vail’s empire last year have so far failed to materialize, even as gushers of early-season snow have funneled hordes of skiers to the mountains. In the West, Vail actually opened several of its western ski areas ahead of schedule, demonstrating not only strong management, but a ready ability to recruit frontline workers in a difficult hiring environment. Their Northeast resorts were among the first to open in the region, and, at one point, nearly half the open ski areas in Vermont and New Hampshire were Vail properties. The company is still muddling along in the Lower Midwest – they need to take notes from Perfect North and Snow Trails, which beat them to open again – but so far 2022-23 is looking like a solid comeback season for Vail Resorts.

5) Vail lands in Europe

Epic Pass holders have been able to access Euro ski-circuses for years, through sometimes conditional and confusing partnerships with resorts in France, Italy, Austria, and Switzerland. But Vail Resorts leveled up in March, purchasing a majority stake in Andermatt-Sedrun, a Swiss resort that sprawls over a series of valleys and peaks.

This is a big deal. With Epic Pass sales reaching their probable upper limit as skiers traumatized by ticket-window prices switch to the Epic Day Pass, Vail is about out of ways to grow within its current footprint. The company isn’t exactly maxed out, resort-wise, in North America, but there aren’t that many ski areas left to buy that are attractive and likely to be for sale anytime soon. As a publicly traded company, Vail has to grow forever or be ostracized. Thus: Europe. The greatest ski market on the planet. Per-capita skier numbers in Austria, Germany, Italy, France, and Switzerland dwarf the numbers in the U.S. There are thousands of ski areas in Europe. Thousands. Vail just bought part of one. The potential here is incomprehensible. If Vail can step lightly on the cultural side, Euro-Ski could be the biggest part of the company’s holdings within a decade or two.

6) U.S. skier visits hit record

Last year wasn’t a great ski season. Snowfall was well below average in most regions – and 21 inches below the 10-year average nationwide. Industrywide labor shortages often made lifts and terrain slow to open. Covid was still kicking around and messing things up. It didn’t matter: a record number of skiers turned out to shred whatever they could. Operators recorded 61 million skier visits last season, according to the National Ski Areas Association.

What drove this surge? A few things, I suspect: widespread access to cheap multi-mountain passes, the continuation of the Covid-era outdoor boom, and ever-better snowmaking that makes lift-served skiing less-reliant on natural snow. But, whatever drove people to ski, it’s a good thing. And with strong early-season snow to start 2022-23, I doubt last year’s record will stand for long.

7) A lift building boom meets a global supply chain in crisis

With record numbers of skiers clicking in, resorts suddenly have money to invest. In 2020, the year Covid hit, North American ski resorts installed 28 new or used lifts, according to Lift Blog. This year, they are aiming to erect 66 (some of these projects will bleed into early 2023). Another 56 (so far), may be coming next year. It’s been decades since this level of sustained infrastructure investment hit the continent’s ski resorts.

Many of these lifts – the Colter six-pack serving the expansion at Grand Targhee, the Base-to-Base Gondola at Palisades Tahoe, eight-packs at Sunday River and Boyne Mountain, a new-used quad serving an expansion at Lookout Pass – will be transformative. The problem has been getting them all built. There just aren’t that many lift manufacturers – Leitner-Poma of America and Doppelmayr build most of the continent’s machines – and they’ve struggled to meet demand as global supply chain issues have delayed components large and small. New lifts at Alta and Jackson Hole were slowed not by the complex technical requirements of a modern high-speed lift, but by shipping delays of that most basic of parts: the haul rope.

When I hosted Leitner-Poma of America President Daren Cole on the podcast last month, he detailed the measures his company was taking to re-jigger their supply chain for 2023. We’ll find out soon if it was enough.

8) Three ski areas change their names

Even with 473 active ski areas in the United States, name changes are rare in skiing. There are good reasons for that. Such exercises are often hard and expensive and unpopular, regardless of how deftly the operators handle them. Skiers tend to adopt their favorite ski areas as a part of their identity, and involuntary changes to that identity can feel intrusive.

But sometimes they’re necessary, and three U.S. ski areas discarded their names this year: two in what amount to modernization exercises, and one to honor its history and bribe locals into liking its new conglomerate owners. “Suicide Six,” one of the smallest Vermont ski areas with a chairlift, but one that had been around since 1936, changed its name to the more palatable “Saskadena Six,” a name that means “standing mountain” in the language of the native Abenaki tribe. The awkwardly named “Big Snow,” a Michigan resort made up of the side-by-side ski areas Indianhead and Blackjack, became, simply, “Snowriver,” a made-up name spun out of the imagination of Charles Skinner, the longtime owner of Lutsen and Granite Peak, who purchased the Michigan property last summer. And after acquiring Shawnee Peak, Maine last year, Boyne Resorts changed the ski area’s name back to “Pleasant Mountain,” which had been its moniker for 50 years before the owners of Pennsylvania’s Shawnee Mountain had purchased the resort and given it a matching name in 1988.

I’ve heard little grumbling about any of the new names, and “Pleasant Mountain” seemed to be the rare social media grand slam, with the ski area’s locals universally praising the decision. But the changes in Vermont and Michigan underscore a fairly obvious point: as societal mores change, operators seem to have little appetite for defending outmoded names, preferring to change them and keep moving.

9) Jay Peak finally sells

For a long time, Jay Peak sat on a shelf, unsold and seemingly unwanted. It was weird. New England’s greatest ski area, a ward of the state, under the stewardship of a Florida lawyer. How did we get here, and why are we still here half a dozen years later?

It gives me great joy to say, finally: who cares? It’s over. On Nov. 1, Utah-based Pacific Group Resorts took ownership of Jay Peak after out-bidding two still-unidentified parties with a $76 million final offer. It was, perhaps, the best possible outcome for Jay Peak and New England skiers. Vail and Alterra own enough of Vermont already. Variety of ownership is a good thing, especially in skiing. Jay can proceed with the benefits of a larger group that can afford the ski area’s very-needed capital investments, without drawing the crowds that are suffocating some of its downstate neighbors. For now, the mountain will remain on the Indy Pass, the coalition’s snowy crown jewel at the top of the country.

Jay was not the only ski area to settle into new ownership this year. Snowriver and China Peak both become the third leg in a regional stool – the former joining Midwest Family Resorts’ powerhouse of Lutsen, Minnesota and Granite Peak, Wisconsin; the latter squatting between Southern California’s Mountain High and Dodge Ridge in the Sierras. Plenty of little regional places have new owners as well: Willard, New York; Ober, Tennessee; Tussey, Pennsylvania; Dry Hill, New York; and Whitecap, Wisconsin.

The most obvious anticipated sale for next year is Burke, former Jay Peak sister resort in northern Vermont. A few small places are for sale as well: New Hermon, Maine; Cockaigne, New York; the defunct former Plymouth Notch ski club in Vermont. The Pennsylvania Department of Parks and Recreation is seeking a new operator for the shuttered and roughed-up Ski Denton. I’m also tapped into a few other in-progress sales that should break soon. The ski area ownership shuffle isn’t slowing down for the foreseeable future.

10) Toggenburg may not be dead yet

In August of last year, Peter Harris, the longtime owner of Labrador and Song ski areas in Central New York, purchased and immediately closed Toggenburg, a similarly sized mountain that sat just a few miles away. This punctured a long-standing community that had gathered at the ski area for generations, as Snow Ridge General Manager Nick Mir, who grew up skiing Togg, detailed for me on the podcast in April. But while the move felt crass - a business-over-emotion decision that, Harris told me, would make the surviving ski areas stronger - the saga seemed like it was over.

Not so. In October, New York Attorney General Letitia James sued Intermountain Management – the umbrella company that owns Lab and Song – “for buying its main competitor, Toggenburg Mountain, then shutting it down to direct skiers to its own mountains.” This move, the AG argued, harmed consumers “by eliminating a competitor without any procompetitive justification.” She is seeking to force Harris to sell one of his resorts and to “restore Toggenburg’s position as an independent competitor.”

The New York AG is one of the most powerful in the country, and the outcome of this case will resonate widely. And while buying-and-closing competing ski areas is not a strategy that anyone else has tried, there is an unhealthy concentration of single-operator ownership in certain regions – why is Vail allowed to own four of the five public ski areas in Ohio, or eight of the 22 ski areas in Pennsylvania? A long time ago, the U.S. Department of Justice forced Vail to sell A-Basin, arguing that the company couldn’t own that and Keystone and Breckenridge. The Feds don’t seem to care much about ski area consolidation anymore, but perhaps this case could make them notice again.

11) Sierra-at-Tahoe returns from the ashes

The worst ski-area story of 2021 turned into the best ski-area story of 2022. Sierra-at-Tahoe, the 2,000-acre locals haunt that was chewed up by last year’s Caldor Fire, re-opened on a dramatically altered footprint after 14 intensive months.

In reshaping itself after a fire that it barely survived, Sierra-at-Tahoe represents both skiing’s worst-case present and its best-case future. Many Western ski areas, particularly those with no or limited snowmaking, are firetraps, with steep and remote terrain that can be hard to tame once ignited. Sierra-at-Tahoe won’t be the last ski area to burn. But the fact that the resort was able to weather an idle year while completely re-imagining its footprint, repairing most of its chairlifts, and replacing millions of dollars’ worth of groomers and other equipment, shows what is possible even when Hell shows up with a fruit basket.

12) Ski ends its print run, finishing off legacy ski media

The Storm is a product of opportunity. With digital ski media uncompromisingly obsessed with Rad Brahs radding out and the print ski media shriveled, I saw an opportunity in 2019 to cover the lift-served skiing universe - where 99 percent of skiers spend 99 percent of their time - with the focus it deserved. But I kind of hoped the ski mags would find a way to come back. I came up reading Powder, Skiing, Ski, and others, and I relished their blend of full-page photography and long-form adventure stories.

But Powder shut down in 2020. Skiing has been gone for five years. Ski was pretty much all that remained. Now that’s gone too. A few months ago, the magazine unceremoniously announced that the November issue would be its last. The publication lives on, of course, part of Outside’s bizarre and incomprehensible “Outerverse.” Perhaps it will thrive there. I hope it does. But someone needs to bring back the great ski magazine. Freeskier is left, sure, but they sent me an email on Nov. 22 promoting an “exclusive” story – that Sun Peaks had joined the Ikon Pass. I had, of course, already covered that story – on Oct. 4, the minute Ikon announced the addition. We don’t need ski magazines to do a bad job of doing things that are being done elsewhere – we need them to do things that can’t be done in any other format. Who wants the job?

The Storm publishes year-round, and guarantees 100 articles per year. This is article 138/100 in 2022, and number 384 since launching on Oct. 13, 2019. Want to send feedback? Reply to this email and I will answer (unless you sound insane or, more likely, I just get busy). You can also email skiing@substack.com.

Thanks for the excellent recap. For someone like me who once worked in the industry, but moved on to other work for the bulk of my adult life, I still love the vibrancy of this great outdoor sport, and greatly appreciate the people who make it happen, from senior leadership to frontline hourly workers. Your work to report on the dynamics of the industry teaches me something new every month. Thanks again and I hope 2023 is another rewarding year for you!

Stuart, I think you creating The Storm in late 2019 couldn't have been better timing... It's been an absolutely wild past few years for the world of lift served skiing!

As always, you are worthy of another Snowbel Prize nomination, you make a Western skier like me want to grab my Indy and Ikon Pass and shred the Midwest and East Coast, a testament to how in-depth and articulate your writing is! Happy New Year's good man, glad you've joined the rest of us back on the slopes.