Who

Taylor Middleton, President and Chief Operating Officer of Big Sky Resort, Montana

Recorded on

April 4, 2022

About Big Sky

Click here for a mountain stats overview

Owned by: Boyne Resorts

Base elevation: 6,800 feet at Madison Base

Summit elevation: 11,166 feet

Vertical drop: 4,350 feet

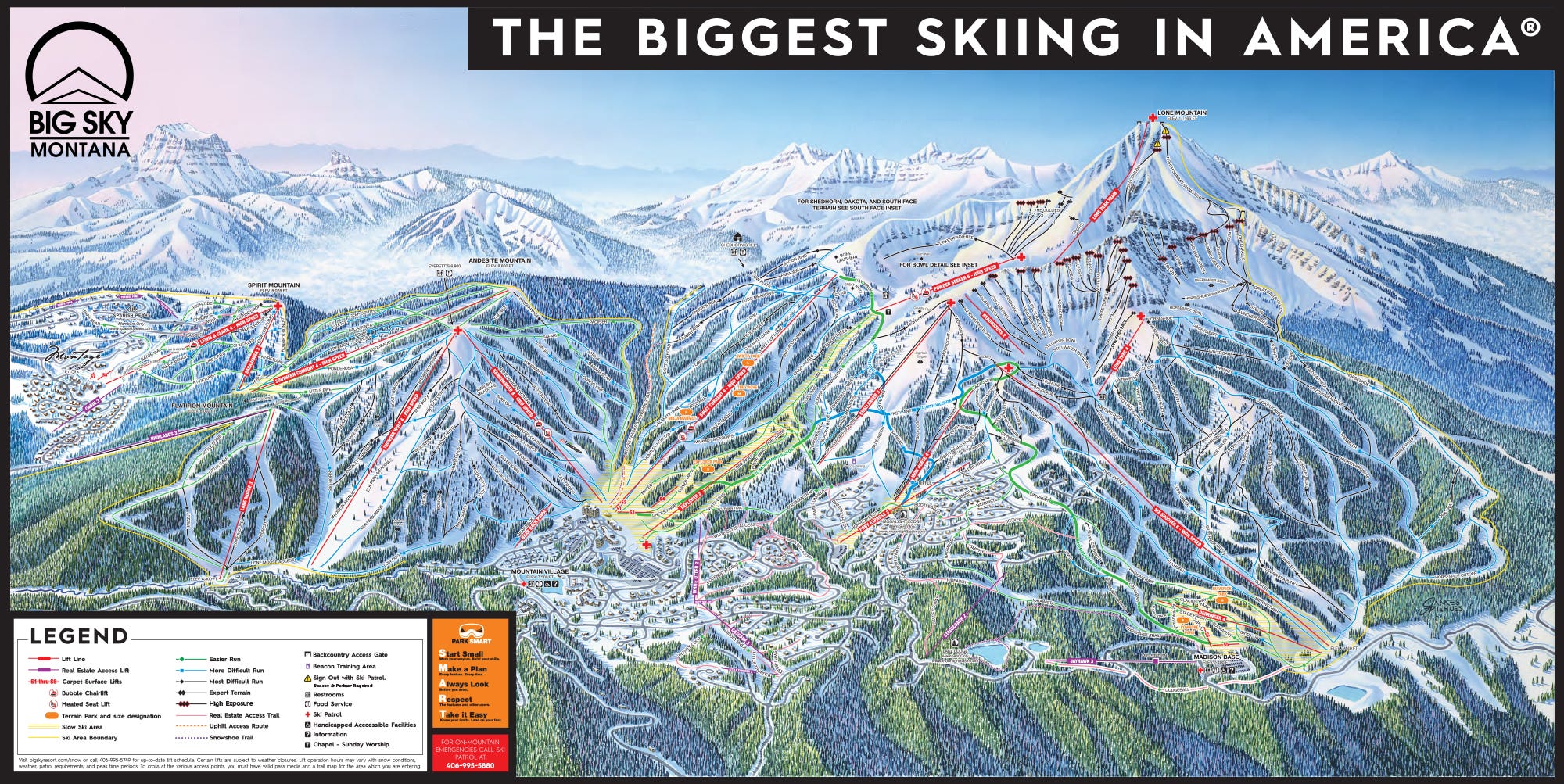

Skiable Acres: 5,850

Average annual snowfall: 400-plus inches

Trail count: 300 (18% expert, 35% advanced, 25% intermediate, 22% beginner)

Terrain parks: 6

Lift count: 39 (1 15-passenger tram, 1 high-speed eight-pack, 3 high-speed six-packs, 4 high-speed quads, 3 fixed-grip quads, 9 triples, 5 doubles, 3 platters, 2 ropetows, 8 carpet lifts) – View Lift Blog’s inventory of Big Sky’s lift fleet.

Uphill capacity: 41,000 skiers per hour

Why I interviewed him

Big Sky opened in 1973, as the American ski industry’s big-mountain land grab was fizzling. Seven years later, Taylor Middleton wandered into town, an Alabama boy wired for adventure. What he found an hour and five minutes south of Bozeman, population 21,645 at the time, was a backwater bump of the sort that still populate the Montana wilds: four or five lifts, 20 or so runs, Lone Peak hovering godlike over it all. A hell of a view and dumptrucks worth of snow and not a whole lot else.

Over the next 42 years, Big Sky would evolve into one of North America’s great ski areas. The Storm, as regular readers know, can be prone to hyperbole. My worldview is tilted toward ennoblement. Even the scraggliest lift-served snowsliding outposts have virtue in their histories, their idiosyncrasies, their improbable continued existence in a world that frustrates such ventures in 10 dozen ways.

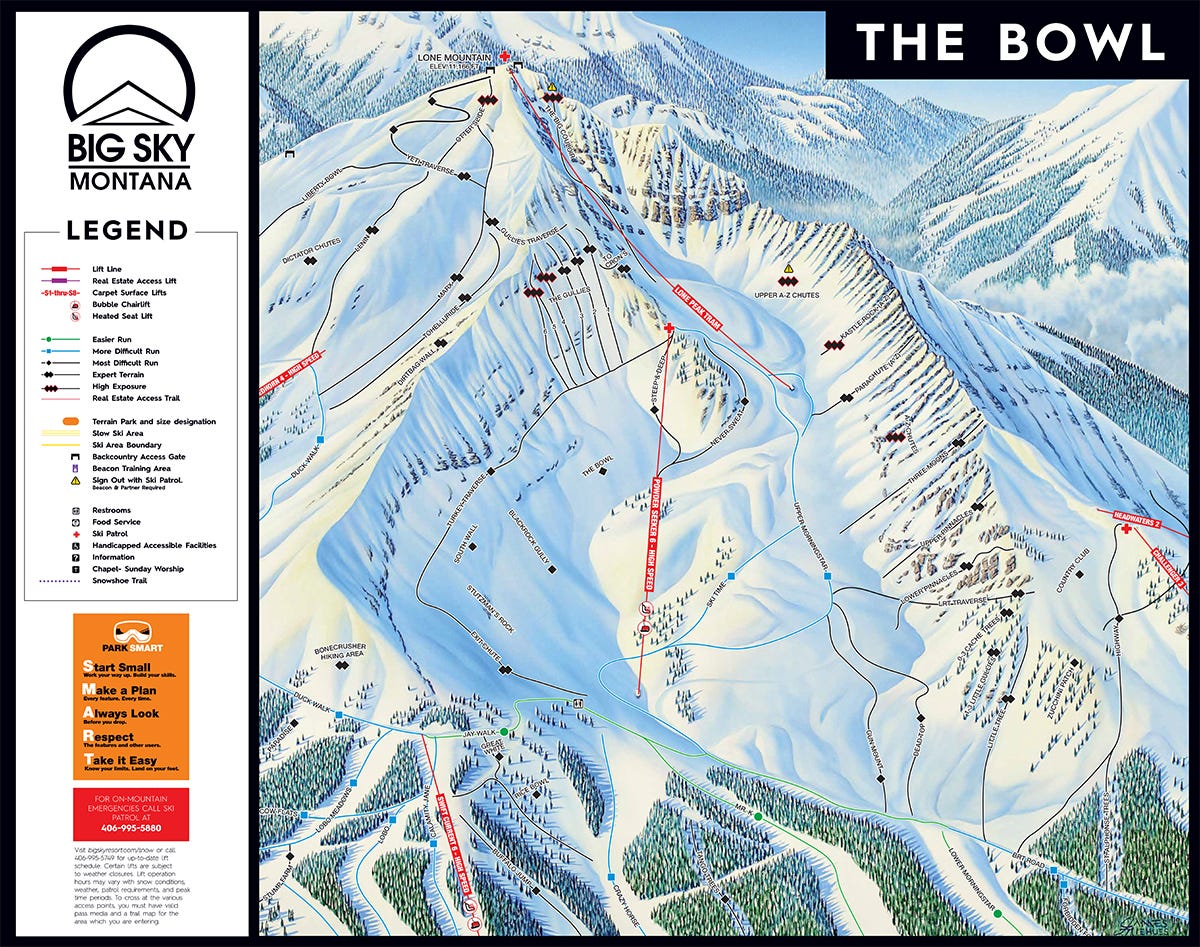

That won’t be necessary here. Big Sky is titanic, sprawling, impossible. Alps-like in its scale and above-treeline drama. Mixed into the 300 named trails are two dozen-ish triple black diamonds. They mean it: to ski Big Couloir or North Summit Snowfield off the top of the tram requires an avalanche beacon, a partner, and a sign-out with Patrol.

But this radness is a small part of the experience. At almost 6,000 acres, Big Sky is nearly the same size as Boyne’s other nine resorts combined*. It is the third-largest ski area in the United States, and it took the combination of Park City with neighboring Park West (7,300 acres), and the connection of the Alpine Meadows and Olympic sides of Palisades Tahoe (6,000 acres) to out-big Big Sky (Big Sky is itself the combination of two ski areas, as it absorbed the old Moonlight Basin in 2013). Even when the base-to-base gondola finally cracks open over Tahoe next year, Palisades Tahoe’s terrain will remain fragmented. Endless, nearly boundless skiing of the sort that defines Big Sky is rare in America.

Which takes us back to Middleton. Big Sky could have been a lot of things in underdeveloped Montana. A rugged single-chair backwater like Turner. A teaser that stopped short of the looming snowfields, like Teton Pass. A fun but lost-in-time burner like Lost Trail. A regional hotshot like Bridger Bowl, with slow lifts, rad terrain, and lots of hiking. Instead it’s one of the most complete and up-to-date ski resorts in North America. How did that happen? Most American ski resorts are just old enough that the pioneering generation, the one that actualized a dream out of the wilderness, are long gone. Big Sky will be 50 years old next year, but for a lot of reasons – not the least among them a stable ownership group (Boyne has owned the ski area since 1976) – a lot of the people who helped mold the place into a monster are still around.

Middleton did not just watch all of this happen – he’s a big part of the reason it happened at all. I wanted to hear his story, and the story of the mountain, firsthand.

*Boyne’s nine other ski areas total 7,200 acres: Summit at Snoqualmie (1,981 acres), Sugarloaf (1,230), Brighton (1,050), Sunday River (870), Cypress (600), The Highlands at Harbor Springs (435), Boyne Mountain (415), Loon (370), and Shawnee Peak (249).

What we talked about

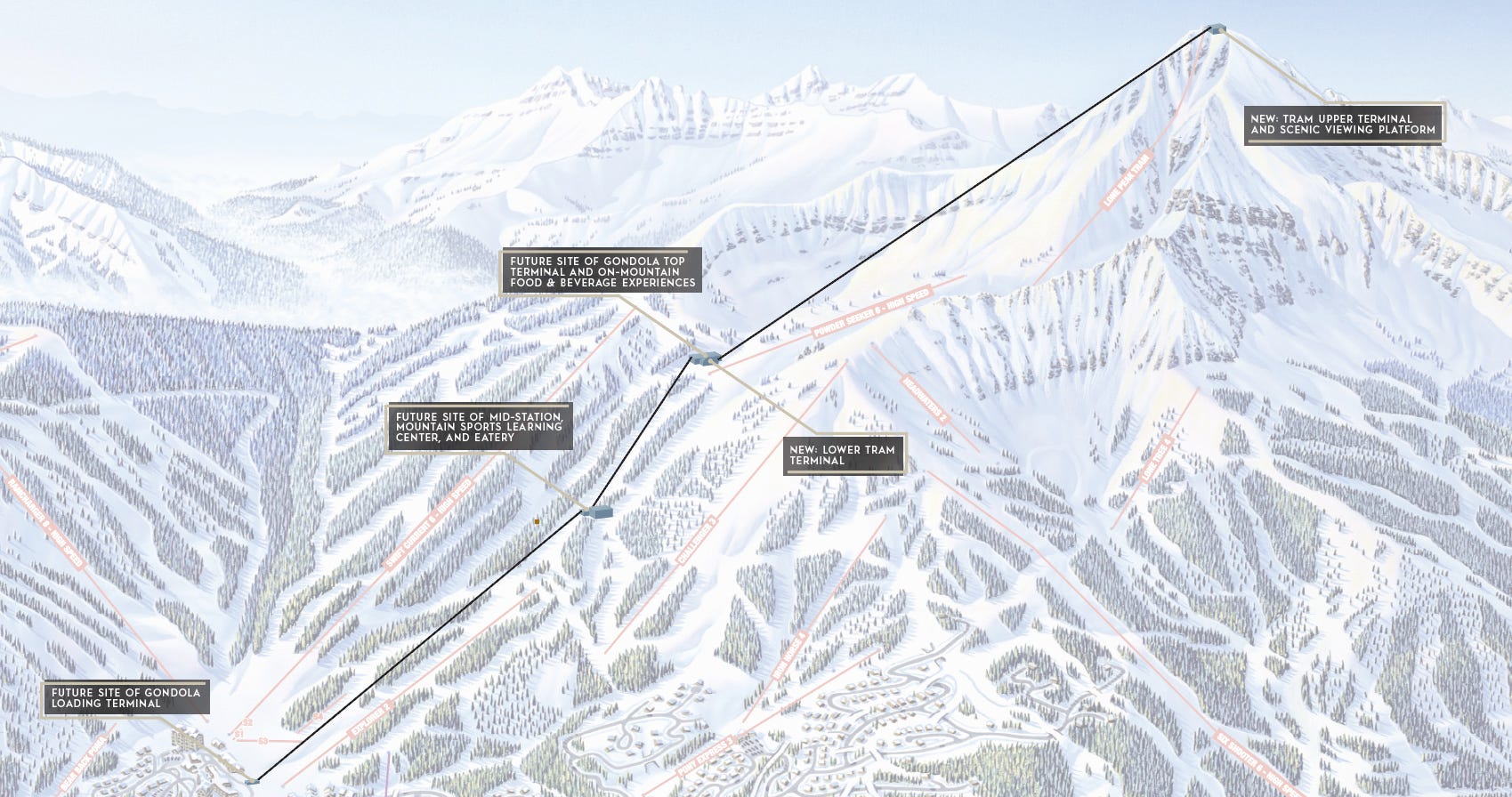

The 2021-22 ski season so far at Big Sky; how an Alabama boy ended up running one of the biggest ski resorts in America; yes there is a ski area in Alabama; dusty, cow-town Bozeman and Big Sky circa 1981; how the mountain grew from a backwater bump with five lifts and 20 runs to a sprawling behemoth that sits alongside the best resorts on the continent; the audacity of the Lone Peak Tram; installing a secret summit lift without the knowledge of the company’s CEO; like a glacier the tram base crawls across the valley; how and why the tram has no towers; how Big Sky’s reputation changed when the tram popped open in 1995; the wild terrain hanging off the summit of Lone Peak; “there’s not an easy way down”; how Patrol tamed the mountain to make it skiable; the power of skier self-selection; the inbounds runs that require Patrol check-in and avy equipment; why Big Sky limits Big Couloir to eight skiers an hour; why skiing got so lame in the ‘80s and how the Lone Peak tram helped nudge the industry out of its stupor; John Kircher and putting skiing first; the good old days of walking right onto the tram; the tram reservation system, how it’s worked out, and whether it’s here to stay; going deep on Big Sky’s forthcoming mega-gondola-tram network; the location of the new tram, its terminals, and its single tower; the fate of the current tram’s terminals; characteristics of the new tram cabins; why Big Sky removed its original two gondolas and why it’s bringing that sort of lift back; the fastest lift on the mountain; an overview of the new gondola; the advantages of operating on private land; Big Sky hates liftlines; when we’ll be able to ride these monster new lifts; where we may see new or upgraded lifts; how close we may be to a second out-of-base lift at Moonlight Basin, where it would run, what it might be called, and what sort of lift we could see; “there are little pods of terrain all over our mountain that we haven’t cleared yet”; how Big Sky came to absorb the formerly independent Moonlight Basin and how it changed the ski area as a whole; Big Sky’s 360-degree ski experience; an encomium to James Neuhaus; how the initial Ikon Pass backlash from 2018-19 has aged; why the resort will require Ikon reservations next season; why Big Sky remained on the Ikon Base Pass as Aspen, Jackson Hole, and others fled, and whether leaving that tier for the Base Plus is still a possibility; the power of Boyne’s network and how it’s helped prop the company up from within over the decades; “I’m getting really tired of pulling Sugarloaf stickers off my lifts”; Boyne’s tiered pass products and how they manage crowds while creating options for everyone; and Big Sky’s commitment to building employee housing.

Why I thought that now was a good time for this interview

For most of its existence, Boyne Resorts has made a brand out of statement lifts, inventing, with its partners, the triple chair and the quad in the 1960s. Boyne brought America’s first six-pack in 1992 (at Boyne Mountain), and the country’s first eight-pack in 2018 (at Big Sky), trailing Europe on the latter but soundly stomping its American competitors. Still, compared to its peers, Big Sky doddered along with a rattletrap lift fleet for decades. By the time Big Sky installed its fourth high-speed lift in 2004*, Vail Mountain already had 15 of them (and had since at least 2001).

But over the past half-dozen years, Boyne has gotten aggressive. By next season, four of its 10 ski areas will have the monster eight-packs already in place at Big Sky and Loon – 80 percent of all such lifts on the continent. A major promised component of the company’s 2030 plans is beefed-up lift infrastructure at Sunday River, Sugarloaf, Loon, Boyne Mountain, and The Highlands at Harbor Springs. But the most dramatic changes are coming to Big Sky, Boyne’s flagship.

After rolling out four high-speed lifts in five years (the Powder Seeker six in 2016, Ramcharger 8 and the Shedhorn high-speed quad in 2018, and the Swift Current 6 in 2021), Big Sky recently unveiled a gargantuan base-to-summit lift network that will transform the mountain, (probably) eliminating Mountain Village liftlines and delivering skiers to the high alpine without the zigzagging adventure across the now-scattered lift network. Skiers will board a two-stage out-of-base gondola cresting near the base of Powder Seeker before transferring to a higher-capacity tram within the same building. This second machine will likely be a hauler in the spirit of the school-bus-shaped big-boys at Jackson and Snowbird (though it will, as Boyne Resorts CEO Stephen Kircher told me, have outward-facing seats), and will certainly haul more skiers than the current 15-passenger version, which is a triumph of engineering but one built for a different time. The whole complex will sit like this in relation to the current lift network:

Once this titanic project is finished, Big Sky may be closer to complete than its enormous lift count (39) suggests. Eight of the remaining lifts are carpets. Ten more are designated “real-estate lifts” and are of no consequence to the on-the-mountain ski experience. As the sparkling new out-of-base fleet materialized, once-promised upgrades to Southern Comfort, Iron Horse, and Lone Moose disappeared from the 2025 plan. But none of these feel particularly consequential. Southern Comfort is a detachable quad, not even 20 years old. Iron Horse is a fixed-grip quad, but it was installed in 1994 and probably has plenty of useful life remaining. Lone Moose, a Yan triple that arrived used from Keystone in 1999, suggests the most pressing need for an upgrade, but it’s tucked at the far end of the resort and serves just a handful of runs – there are better places to spend money.

The most obvious place is the Madison Base, above which 2,000 acres of former Moonlight Basin terrain rises toward Lone Peak. Aside from a beginner quad, the Six Shooter six-pack serves this entire area. The possibility of another lift here is tantalizing, and we discuss this in depth on the podcast. Also, terrain expansion could be coming, here and elsewhere around the ski area. “There are little pods of terrain all over the mountain that we haven’t developed yet,” Middleton told me.

There is a logic to this improvisational, discuss-one-thing-and-do-another swagger that Big Sky has: the place sits entirely on private property. This is a rare situation for a large Western U.S. resort, most of which sit on Forest Service land and operate under long-term leases. That means that the master plans, the public comment periods, the endless back-and-forth with the Forest Service, the perpetual scaling back of grand plans – none of that is Big Sky’s problem. As Boyne tips over its Money Bin and empties it into its Montana crown jewel, we are witnessing an interesting real-time experiment in private willfulness versus the public-private model upon which so much of our big-resort infrastructure rests. Don’t tell Free Market Bro, but the more Boyne proves it can act as a responsible mountain steward without turning the place into a set piece from the latter half of The Lorax, the more I like Big Sky’s model.

*When the Six Shooter high-speed six-pack came online in 2003, Moonlight Basin was still a separate resort.

Questions I wish I’d asked

However. I don’t really understand if Boyne is truly in a yeah-let’s-just-build-like-nine-hot tubs-in-a-bear-den free-for-all situation or not. Just because the resort is not subject to Forest Service approvals (which, frankly, have allowed far more ski resort development than they have shut down over the past six decades), does not mean it can just do whatever the hell it wants all the time. Probably. I don’t know because I didn’t ask, and I probably should have. I will say that Boyne has emphasized its role as an environmental steward more and more over the past decade, joining Powdr, Vail, and Alterra last year in a “shared commitment around sustainability and advocacy.”

I also would have liked to have gotten more into these “terrain pods all over the mountain.” Which is funny because Big Sky is already like the size of Delaware and I’m all worried about it expanding. But really I started this podcast because I can’t stop thinking about this kind of thing. It’s a form of experiential avarice that I have no other outlet for.

What I got wrong

When I interviewed Jackson Hole President Mary Kate Buckley in November, I accidentally referred to her as the resort’s “CEO.” I then made a correction in the article that accompanied that podcast. And then during this interview I again referred to Buckley as Jackson Hole’s “CEO.” So I’m again printing a correction because apparently I’m a nitwit. I’m sorry Mary Kate you’re doing a great job and you don’t deserve this.

Also, at one point in the interview when we were discussing trailmaps, I referred to “Lone Peak” as “Big Sky.”

Why you should ski Big Sky

Because there are a couple dozen you just have to hit at some point, right? If you’re in North America, it’s these ones. Just about everybody reading this has probably skied some of them, and most of us (outside of Peter Landsman from Lift Blog), have probably not skied all of them. It’s a big list, it’s a big continent, and time and money are not eternal things.

So we all have our calculus on where we go and when. Like a lot of Midwestern- or Eastern-based skiers, my Western travels have been heavily skewed toward whatever is in the orbit of Denver and Salt Lake airports. And why not? The I-70 and Wasatch resorts are enormous, interesting, snowy, and convenient. And, until the advent of the triple-digit walk-up day ticket, affordable (they still are, so long as you plan your ski season like a cicada, securing you earthly access 17 years in advance).

For a long time, Big Sky was the opposite of convenient. Bozeman airport was small, expensive, and hard to reach. The mountain itself was cold and far, with a mostly slow lift fleet. As the mainline Colorado and Utah destinations rapidly modernized in the 80s and 90s, Big Sky took its time.

That time has come. Bozeman airport now welcomes direct flights from 30 markets. Flights are quite affordable. Tens of millions of dollars’ worth of sparkling new lifts strafe Big Sky’s 300 runs. The resort is a headliner on the Ikon Pass. Getting to and skiing Big Sky has never been easier.

And oh yeah the skiing. See trailmap, above. If I need to convince you that Big Sky is worth your time, then what are we even doing here?

More Big Sky

Middleton and I discuss an excellent history of the Lone Peak Tram written by respected ski journalist Marc Peruzzi. This video tells the story very well, and includes footage of a young Taylor Middleton:

The news section of Big Sky’s website is, in general, excellent, with stories written by freelance journalists who appear to have quite a bit of editorial leeway. This is rarer than you would imagine.

We also discussed this letter that Middleton drafted to the Big Sky community in response to Ikon Pass backlash during the 2018-19 season. A response to that.

Oh, and yes, there is a ski area in Alabama, as Middleton and I discussed on the podcast. No, it’s not indoors. It hasn’t opened in a couple years, mostly becaue of Covid-related things, but you can follow their operations on their Facebook page. Frankly it kind of looks like any little bump outside of Milwaukee or Grand Rapids:

A pictorial history of Big Sky’s development

1975

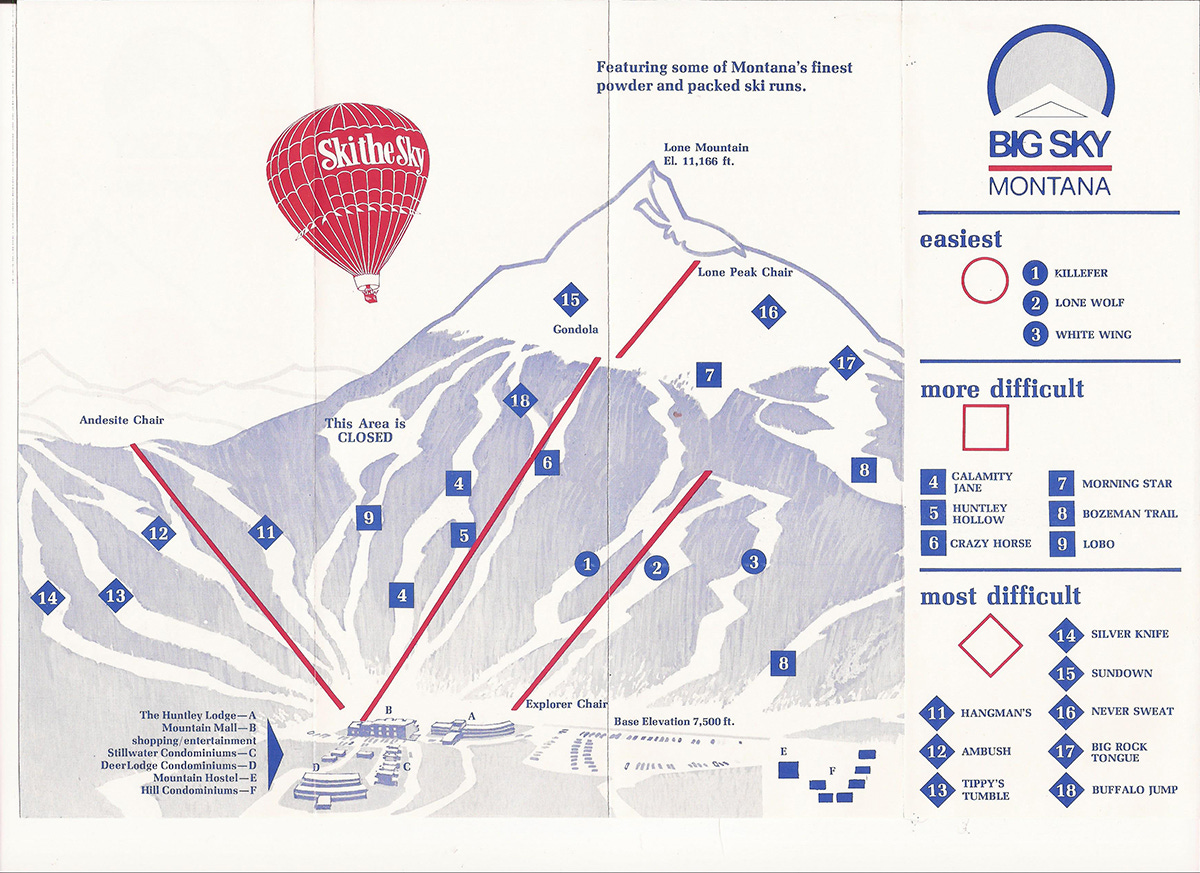

This is the earliest Big Sky map I could find – four lifts and 18 runs, with parking right at the base.

1978

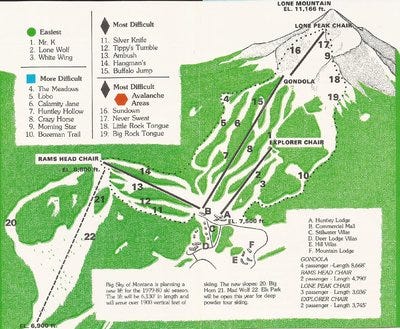

A few years later, the far side of Andesite was online:

1995

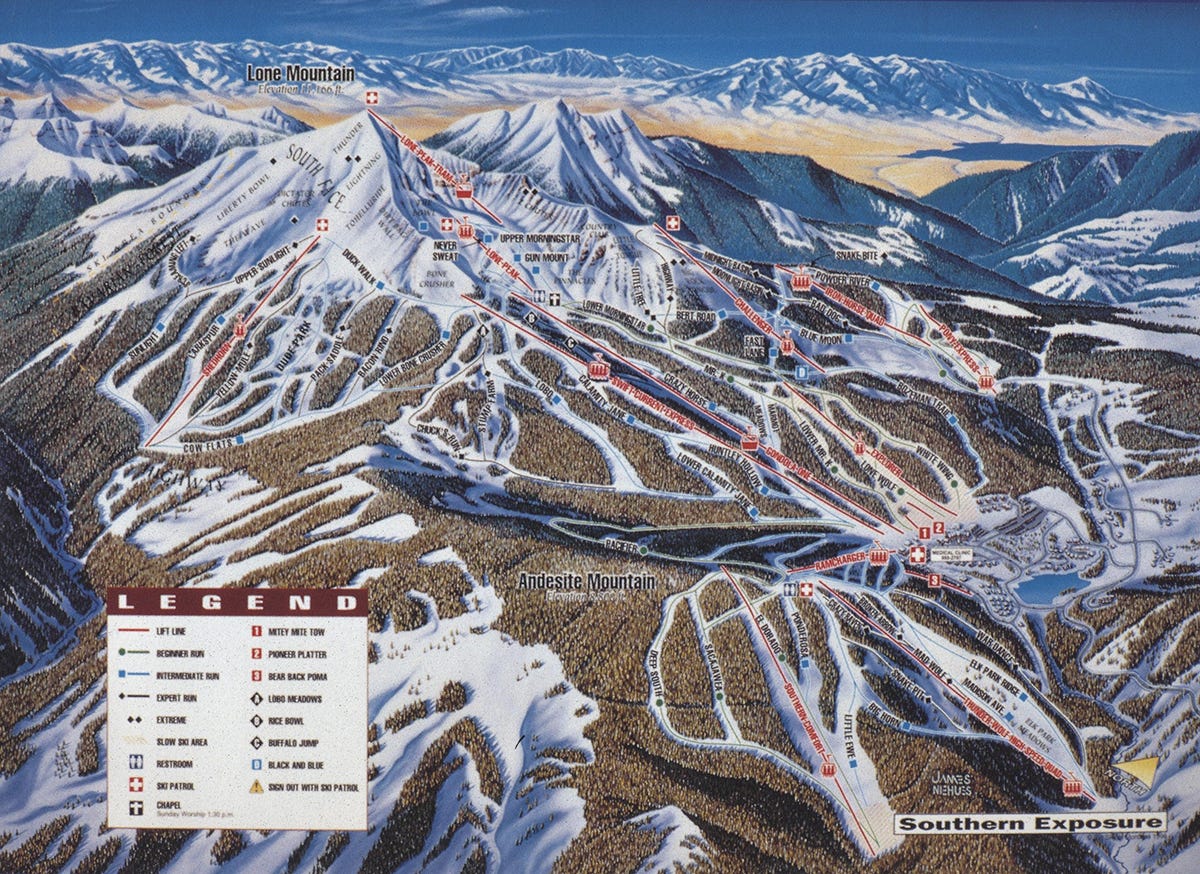

Nearly two decades later, the resort is still relatively contained, but Challenger, Iron Horse, and Southern Comfort add distinct expert, intermediate, and beginner pods on opposite sides of the ski area. Two gondolas now run out of the Mountain Village base in this 1994-95 trailmap:

1997

The tram, installed in summer 1995, changed everything, blowing the resort up to its summit. That same year, Big Sky also ran the Shedhorn double up the backside of the peak:

In 2013, the mountain acquired adjacent Moonlight Basin, giving us the foundation of today’s Big Sky. Boyne CEO Stephen Kircher has told me on numerous occasions that the ski area is committed to keeping its paper trailmaps in perpetuity. Snag one as a memento when you’re there – this place is changing fast, and they won’t be up-to-date for long.

The Storm publishes year-round, and guarantees 100 articles per year. This is article 36/100 in 2022. Want to send feedback? Reply to this email and I will answer (unless you sound insane). You can also email skiing@substack.com.

Podcast #81: Big Sky President and Chief Operating Officer Taylor Middleton