Who

JD Crichton, General Manager of Wildcat Mountain, New Hampshire

Recorded on

May 30, 2024

About Wildcat

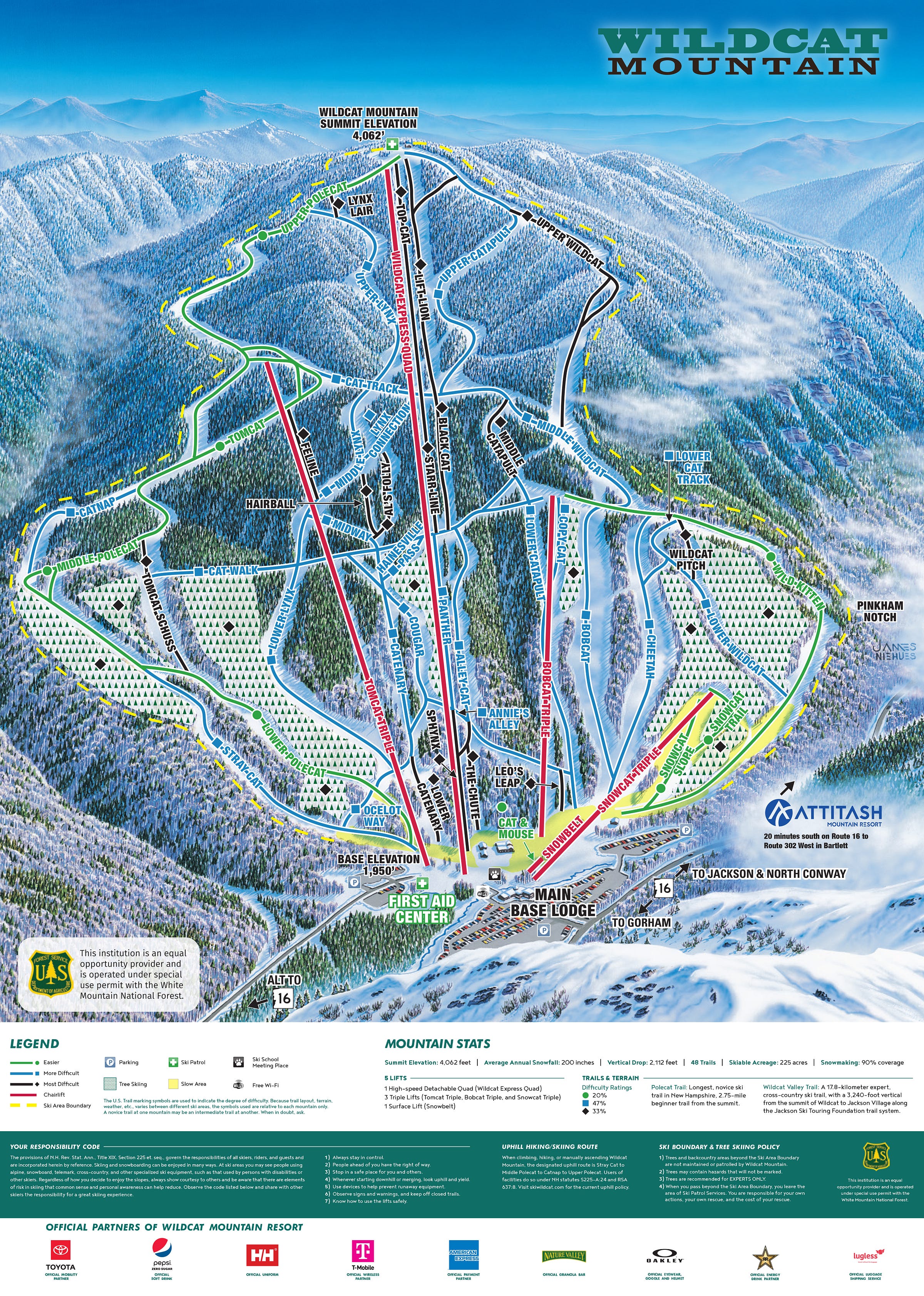

Click here for a mountain stats overview

Owned by: Vail Resorts

Located in: Gorham, New Hampshire

Year founded: 1933 (lift service began in 1957)

Pass affiliations:

Epic Pass, Epic Local Pass, Northeast Value Pass – unlimited access

Northeast Midweek Pass – unlimited weekday access

Closest neighboring ski areas: Black Mountain, New Hampshire (:18), Attitash (:22), Cranmore (:28), Sunday River (:45), Mt. Prospect Ski Tow (:46), Mt. Abram (:48), Bretton Woods (:48), King Pine (:50), Pleasant Mountain (:57), Cannon (1:01), Mt. Eustis Ski Hill (1:01)

Base elevation: 1,950 feet

Summit elevation: 4,062 feet

Vertical drop: 2,112 feet

Skiable Acres: 225

Average annual snowfall: 200 inches

Trail count: 48 (20% beginner, 47% intermediate, 33% advanced)

Lift count: 5 (1 high-speed quad, 3 triples, 1 carpet)

Why I interviewed him

I’ve always been skeptical of acquaintances who claim to love living in New Jersey because of “the incredible views of Manhattan.” Because you know where else you can find incredible views of Manhattan? In Manhattan. And without having to charter a hot-air balloon across the river anytime you have to go to work or see a Broadway play.*

But sometimes views are nice, and sometimes you want to be adjacent-to-but-not-necessarily-a-part-of something spectacular and dramatic. And when you’re perched summit-wise on Wildcat, staring across the street at Mount Washington, the most notorious and dramatic peak on the eastern seaboard, it’s hard to think anything other than “damn.”

Flip the view and the sentiment reverses as well. The first time I saw Wildcat was in summertime, from the summit of Mount Washington. Looking 2,200 feet down, from above treeline, it’s an almost quaint-looking ski area, spare but well-defined, its spiderweb trail network etched against the wild Whites. It feels as though you could reach down and put it in your pocket. If you didn’t know you were looking at one of New England’s most abrasive ski areas, you’d probably never guess it.

Wildcat could feel tame only beside Mount Washington, that open-faced deathtrap hunched against 231-mile-per-hour winds. Just, I suppose, as feisty New Jersey could only seem placid across the Hudson from ever-broiling Manhattan. To call Wildcat the New Jersey of ski areas would seem to imply some sort of down-tiering of the thing, but over two decades on the East Coast, I’ve come to appreciate oft-abused NJ as something other than New York City overflow. Ignore the terrible drivers and the concrete-bisected arterials and the clusters of third-world industry and you have a patchwork of small towns and beach towns, blending, to the west and north, with the edges of rolling Appalachia, to the south with the sweeping Pine Barrens, to the east with the wild Atlantic.

It’s actually pretty nice here across the street, is my point. Even if it’s not quite as cozy as it looks. This is a place as raw and wild and real as any in the world, a thing that, while forever shadowed by its stormy neighbor, stands just fine on its own.

*It’s not like living in New Jersey is some kind of bargain. It’s like paying Club Thump Thump prices for grocery store Miller Lite. Or at least that was my stance until I moved my smug ass to Brooklyn.

What we talked about

Mountain cleanup day; what it took to get back to long seasons at Wildcat and why they were truncated for a handful of winters; post-Vail-acquisition snowmaking upgrades; the impact of a $20-an-hour minimum wage on rural New Hampshire; various bargain-basement Epic Pass options; living through major resort acquisitions; “there is no intention to make us all one and the same”; a brief history of Wildcat; how skiers lapped Wildcat before mechanical lifts; why Wildcat Express no longer transforms from a chairlift to a gondola for summer ops; contemplating Wildcat Express replacements; retroactively assessing the removal of the Catapult lift; the biggest consideration in determining the future of Wildcat’s lift fleet; when a loaded chair fell off the Snowcat lift in 2022; potential base area development; and Attitash as sister resort.

Why I thought that now was a good time for this interview

Since it’s impossible to discuss any Vail mountain without discussing Vail Resorts, I’ll go ahead and start there. The Colorado-based company’s 2019 acquisition of wild Wildcat (along with 16 other Peak resorts), met the same sort of gasp-oh-how-can-corporate-Vail-ever-possibly-manage-a-mountain-that-doesn’t-move-skiers-around-like-the-fat-humans-on-the-space-base-in-Wall-E that greeted the acquisitions of cantankerous Crested Butte (2018), Whistler (2016), and Kirkwood (2012). It’s the same sort of worry-warting that Alterra is up against as it tries to close the acquisition of Arapahoe Basin. But, as I detailed in a recent podcast episode on Kirkwood, the surprising thing is how little can change at these Rad Brah outposts even a dozen years after The Consumption Event.

But, well. At first the Angry Ski Bros of upper New England seemed validated. Vail really didn’t do a great job of running Wildcat from 2019 to 2022-ish. The confluence of Covid, inherited deferred maintenance, unfamiliarity with the niceties of East Coast operations, labor shortages, Wal-Mart-priced passes, and the distractions caused by digesting 20 new ski areas in one year contributed to shortened seasons, limited terrain, understaffed operations, and annoyed customers. It didn’t help when a loaded chair fell off the Snowcat triple in 2022. Vail may have run ski resorts for decades, but the company had never encountered anything like the brash, opinionated East, where ski areas are laced tightly together, comparisons are easy, and migrations to another mountain if yours starts to suck are as easy as a five-minute drive down the road.

But Vail is settling into the Northeast, making major lift upgrades at Stowe, Mount Snow, Okemo, Attitash, and Hunter since 2021. Mandatory parking reservations have helped calm once-unmanageable traffic around Stowe and Mount Snow. The Epic Pass – particularly the northeast-specific versions – has helped to moderate region-wide season pass prices that had soared to well over $1,000 at many ski areas. The company now seems to understand that this isn’t Keystone, where you can make snow in October and turn the system off for 11 months. While Vail still seems plodding in Pennsylvania and the lower Midwest, where seasons are too short and the snowmaking efforts often underwhelming, they appear to have cracked New England – operationally if not always necessarily culturally.

That’s clear at Wildcat, where seasons are once again running approximately five months, operations are fully staffed, and the pitchforks are mostly down. Wildcat has returned to the fringe, where it belongs, to being an end-of-the-road day-trip alternative for people who prefer ski areas to ski resorts (and this is probably the best ski-area-with-no-public-onsite lodging in New England). Locals I speak with are generally happy with the place, which, this being New England, means they only complain about it most of the time, rather than all of the time. Short of moving the mountain out of its tempestuous microclimate and into Little Cottonwood Canyon, there isn’t much Vail could do to change that, so I’d suggest taking the win.

What I got wrong

When discussing the installation of the Wildcat Express and the decommissioning of the Catapult triple, I made a throwaway reference to “whoever owned the mountain in the late ‘90s.” The Franchi family owned Wildcat from 1986 until selling the mountain to Peak Resorts in 2010.

Why you should ski Wildcat

There isn’t much to Wildcat other than skiing. A parking lot, a baselodge, scattered small buildings of unclear utility - all of them weather-beaten and slightly ramshackle, humanity’s sad ornaments on nature’s spectacle.

But the skiing. It’s the only thing there is and it’s the only thing that matters. One high-speed lift straight to the top. There are other lifts but if the 2,041-vertical-foot Wildcat Express is spinning you probably won’t even notice, let alone ride, them. Straight up, straight down. All day long or until your fingers fall off, which will probably take about 45 minutes.

The mountain doesn’t look big but it is big. Just a few trails off the top but these quickly branch infinitely like some wild seaside mangrove, funneling skiers, whatever their intent, into various savage channels of its bell-shaped footprint. Descending the steepness, Mount Washington, so prominent from the top, disappears, somehow too big to be seen, a paradox you could think more about if you weren’t so preoccupied with the skiing.

It's not that the skiing is great, necessarily. When it’s great it’s amazing. But it’s almost never amazing. It’s also almost never terrible. What it is, just about all the time, is a fight, a mottled, potholed, landmine-laced mother-bleeper of a mountain that will not cede a single turn without a little backtalk. This is not an implication of the mountain ops team. Wildcat is about as close to an un-tamable mountain as you’ll find in the over-groomed East. If you’ve ever tried building a sandcastle in a rising tide, you have a sense of what it’s like trying to manage this cantankerous beast with its impossible weather and relentless pitch.

We talk a bit, on the podcast, about Wildcat’s better-than-you’d-suppose beginner terrain and top-to-bottom green trail. But no one goes there for that. The easy stuff is a fringe benefit for edgier families, who don’t want to pinch off the rapids just because they’re pontooning on the lake. Anyone who truly wants to coast knows to go to Bretton Woods or Cranmore. Wildcat packs the rowdies like jacket-flask whisky, at hand for the quick hit or the bender, for as dicey a day as you care to make it.

Podcast Notes

On long seasons at Wildcat

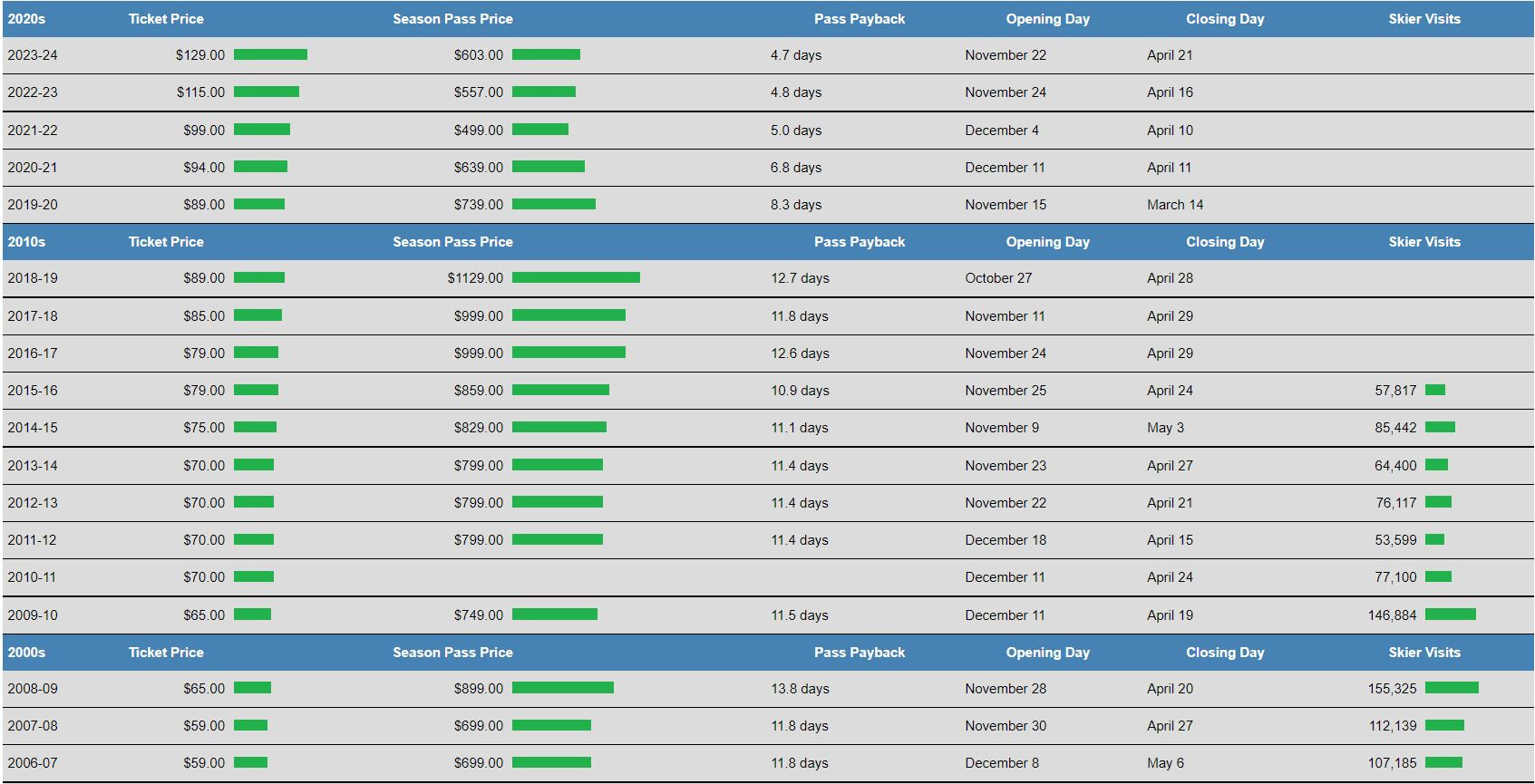

Wildcat, both under the Franchi family (1986 to 2010), and Peak Resorts, had made a habit of opening early and closing late. During Vail Resorts’ first three years running the mountain, those traditions slipped, with later-than-normal openings and earlier-than-usual closings. Obviously we toss out the 2020 early close, but fall 2020 to spring 2022 were below historical standards. Per New England Ski History:

On Big Lifts: New England Edition

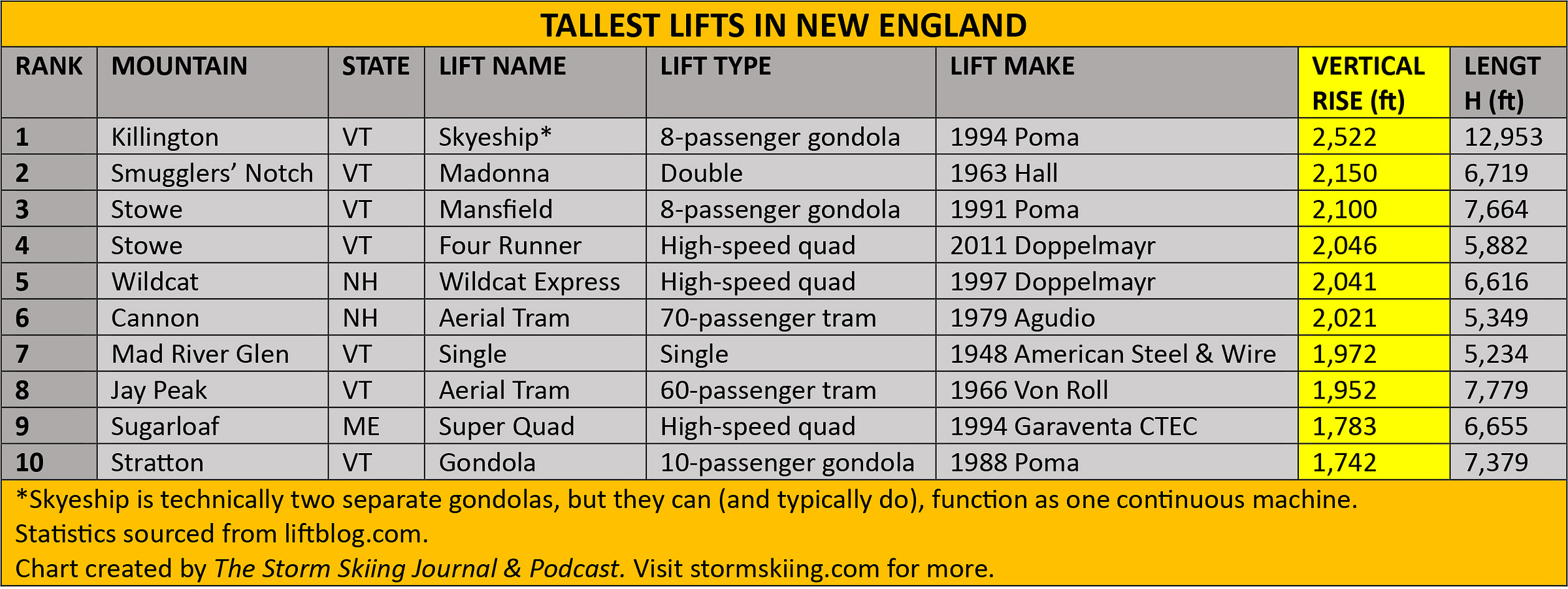

I noted that the Wildcat Express quad delivered one of the longest continuous vertical rises of any New England lift. I didn’t actually know where the machine ranked, however, so I made this chart. The quad lands at an impressive number five among all lifts, and is third among chairlifts, in the six-state region:

Kind of funny that, even in 2024, two of the 10 biggest vertical drops in New England still belong to fixed-grip chairs (also arguably the two best terrain pods in Vermont, with Madonna at Smuggs and the single at MRG).

The tallest lifts are not always the longest lifts, and Wildcat Express ranks as just the 13th-longest lift in New England. A surprise entrant in the top 15 is Stowe’s humble Toll House double, a 6,400-foot-long chairlift that rises just 890 vertical feet. Another inconspicuous double chair – Sugarloaf’s older West Mountain lift – would have, at 6,968 feet, have made this list (at No. 10) before the resort shortened it last year (to 4,130 feet). It’s worth noting that, as far as I know, Sugarbush’s Slide Brook Express is the longest chairlift in the world.

On Herman Mountain

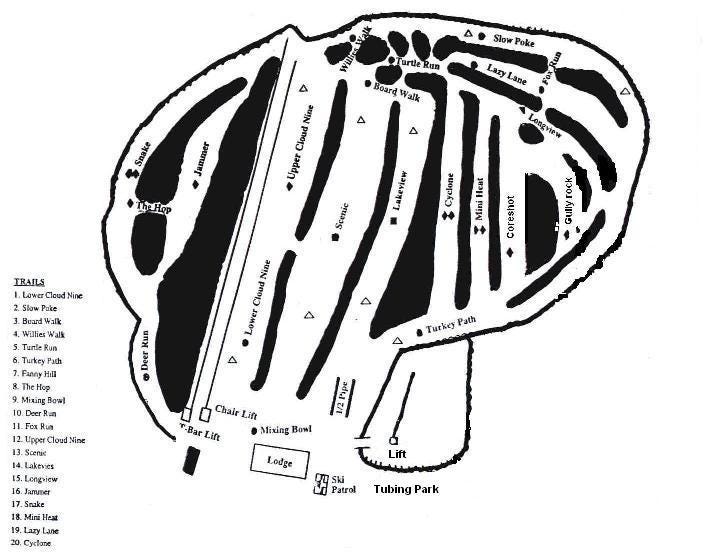

Crichton grew up skiing at Hermon Mountain, a 300-ish footer outside of Bangor, Maine. The bump still runs the 1966 Poma T-bar that he skied off of as a kid, as well as a Stadeli double moved over from Pleasant Mountain in 1998 (and first installed there, according to Lift Blog, in 1967. The most recent Hermon Mountain trailmap that I can find dates to 2007:

On the Epic Northeast Value Pass versus other New England season passes

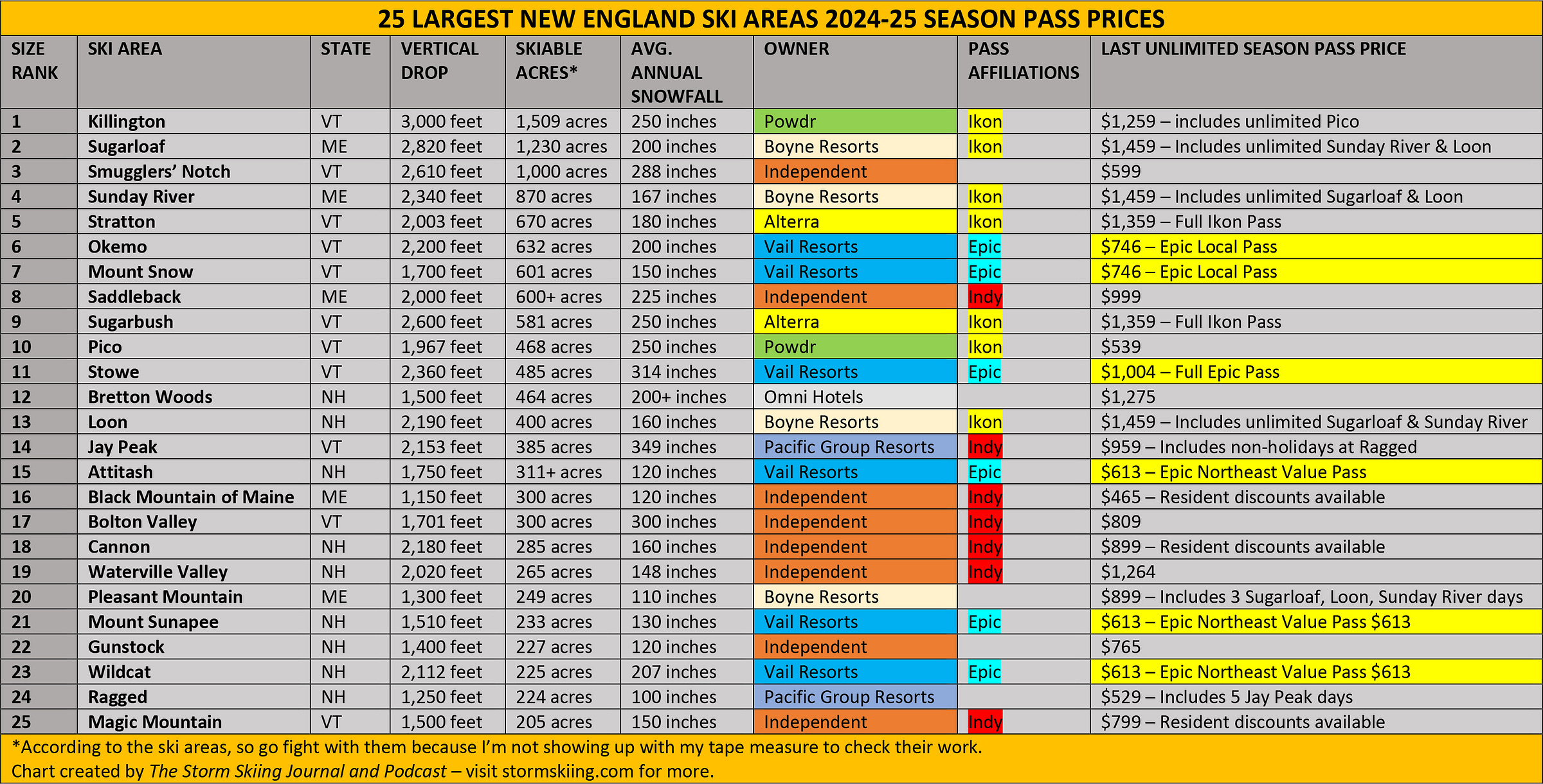

Vail’s Epic Northeast Value Pass is a stupid good deal: $613 for unlimited access to the company’s four New Hampshire ski areas (Wildcat, Attitash, Mount Sunapee, Crotched), non-holiday access to Mount Snow and Okemo, and 10 non-holiday days at Stowe (plus access to Hunter and everything Vail operates in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Michigan). Surveying New England’s 25 largest ski areas, the Northeast Value Pass is less-expensive than all but Smugglers’ Notch ($599), Black Mountain of Maine ($465), Pico ($539), and Ragged ($529). All of those save Ragged’s are single-mountain passes.

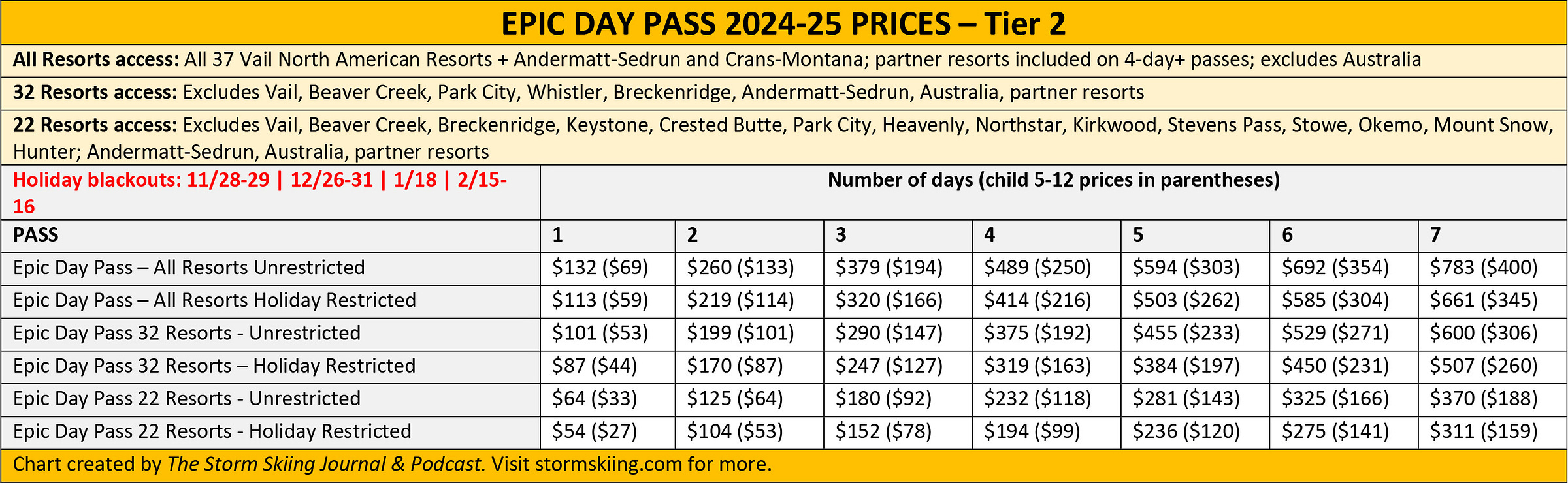

On the Epic Day Pass

Yes I am still hung up on the Epic Day Pass, and here’s why:

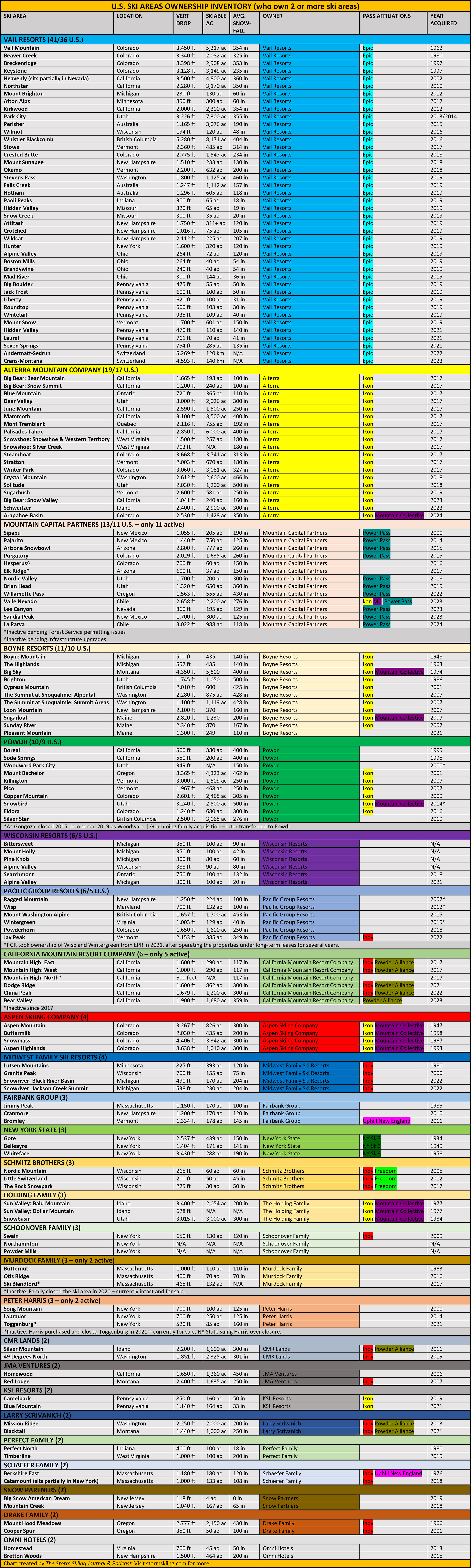

On consolidation

I referenced Powdr’s acquisition of Copper Mountain in 2009 and Vail’s purchase of Crested Butte in 2018. Here’s an inventory all the U.S. ski areas owned by a company with two or more resorts:

On Wildcat’s old Catapult lift

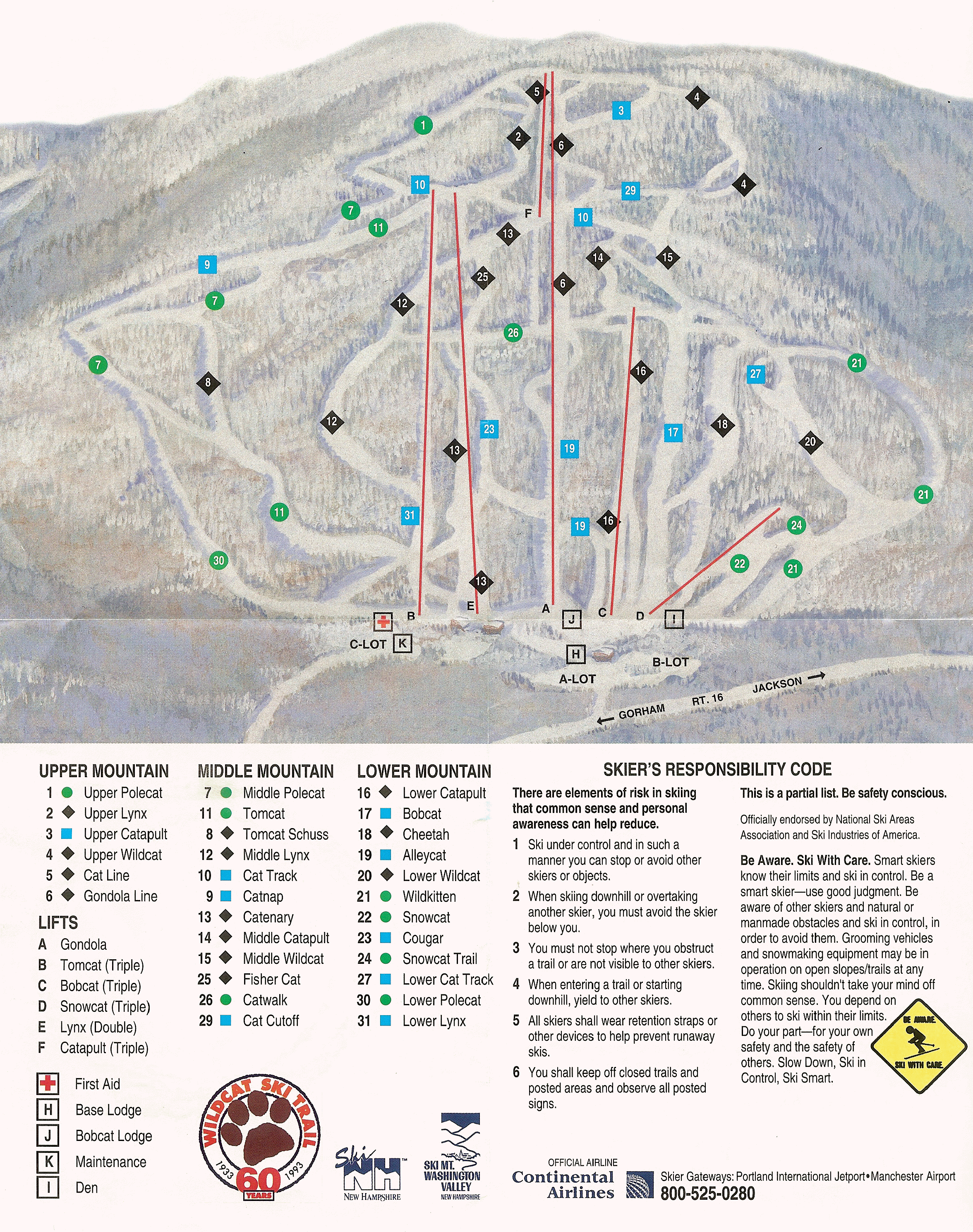

When Wildcat installed its current summit chair in 1997, they removed the Catapult triple, a shorter summit lift (Lift F below) that had provided redundancy to the summit alongside the old gondola (Lift A):

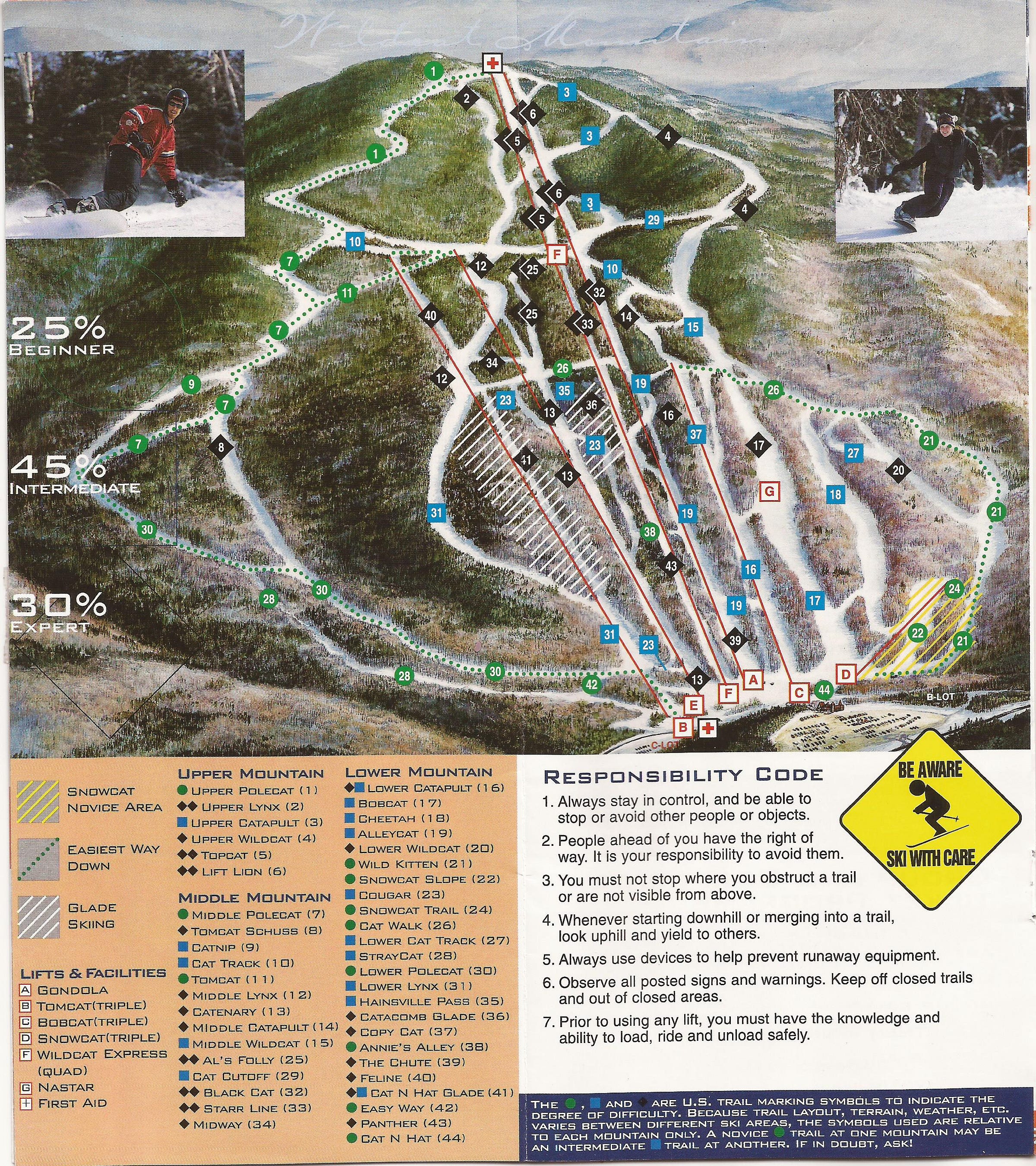

Interestingly, the old gondy, which dated to 1957, remained in place for two more years. Here’s a circa 1999 trailmap, showing both the Wildcat Express and the gondola running parallel from base to summit:

It’s unclear how often both lifts actually ran simultaneously in the winter, but the gondola died with the 20th Century. The Wildcat Express was a novel transformer lift, which converted from a high-speed quad chair in the winter to a four-passenger gondola in the summer. Vail, for reasons Crichton explains in the podcast, abandoned that configuration and appears to have no intentions of restoring it.

On the Snowcat lift incident

A bit more on the January 2022 chairlift accident at Wildcat, per SAM:

On Saturday, Jan. 8, a chair carrying a 22-year-old snowboarder on the Snowcat triple at Wildcat Mountain, N.H., detached from the haul rope and fell nearly 10 feet to the ground. Wildcat The guest was taken to a nearby hospital with serious rib injuries.

According to state fire marshal Sean Toomey, the incident began after the chair was misloaded—meaning the guest was not properly seated on the chair as it continued moving out of the loading area. The chair began to swing as it traveled uphill, struck a lift tower and detached from the haul rope, falling to the ground.

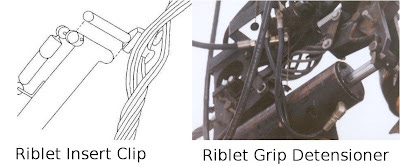

Snowcat is a still-active Riblet triple, and attaches to the haulrope with a device called an “insert clip.” I found this description of these novel devices on a random blog from 2010, so maybe don’t include this in a report to Congress on the state of the nation’s lift fleet:

[Riblet] closed down in 2003. There are still quite a few around; from the three that originally were at The Canyons, only the Golden Eagle chair survives today. Riblet built some 500 lifts. The particularities of the Riblet chair are their grips, which are called insert clips. It is a very ingenious device and it is very safe too. Since a picture is worth a thousand words, You'll see a sketch below showing the detail of the clip.

… One big benefit of the clip is that it provides a very smooth ride over the sheave trains, particularly under the compression sheaves, something that traditional clam/jaw grips cannot match. The drawback is that the clip cannot be visually inspected at it is the case with other grips. Also, the code required to move the grip every 2 years or 2,000 hours, whichever comes first. This is the same with traditional grips.

This is a labor-intensive job and a special tool has been developed: The Riblet "Grip Detensioner." It's showed on a second picture representing the tool in action. You can see the cable in the middle with the strands separated, which allows the insertion of the clip. Also, the fiber or plastic core of the wire rope has to be cut where the clip is inserted. When the clip is moved to another location of the cable, a plastic part has to be placed into the cable to replace the missing piece of the core. Finally, the Riblet clip cannot be placed on the spliced section of the rope.

Loaded chairs utilizing insert clips also detached from lifts at Snowriver (2021) and 49 Degrees North (2020). An unoccupied, moving chair fell from Heavenly’s now-retired North Bowl triple in 2016.

The Storm publishes year-round, and guarantees 100 articles per year. This is article 44/100 in 2024, and number 544 since launching on Oct. 13, 2019.