Who

David Makarsky, General Manager of Camelback Resort, Pennsylvania

Recorded on

February 8, 2024

About Camelback

Click here for a mountain stats overview

Owned by: KSL Capital, managed by KSL Resorts

Located in: Tannersville, Pennsylvania

Year founded: 1963

Pass affiliations:

Ikon Pass: 7 days, no blackouts

Ikon Base Pass: 5 days, holiday blackouts

Reciprocal partners: None

Closest neighboring ski areas: Shawnee Mountain (:24), Jack Frost (:26), Big Boulder (:27), Skytop Lodge (:29), Saw Creek (:37), Blue Mountain (:41), Pocono Ranchlands (:43), Montage (:44), Hideout (:51), Elk Mountain (1:05), Bear Creek (1:09), Ski Big Bear (1:16)

Base elevation: 1,252 feet

Summit elevation: 2,079 feet

Vertical drop: 827 feet

Skiable Acres: 166

Average annual snowfall: 50 inches

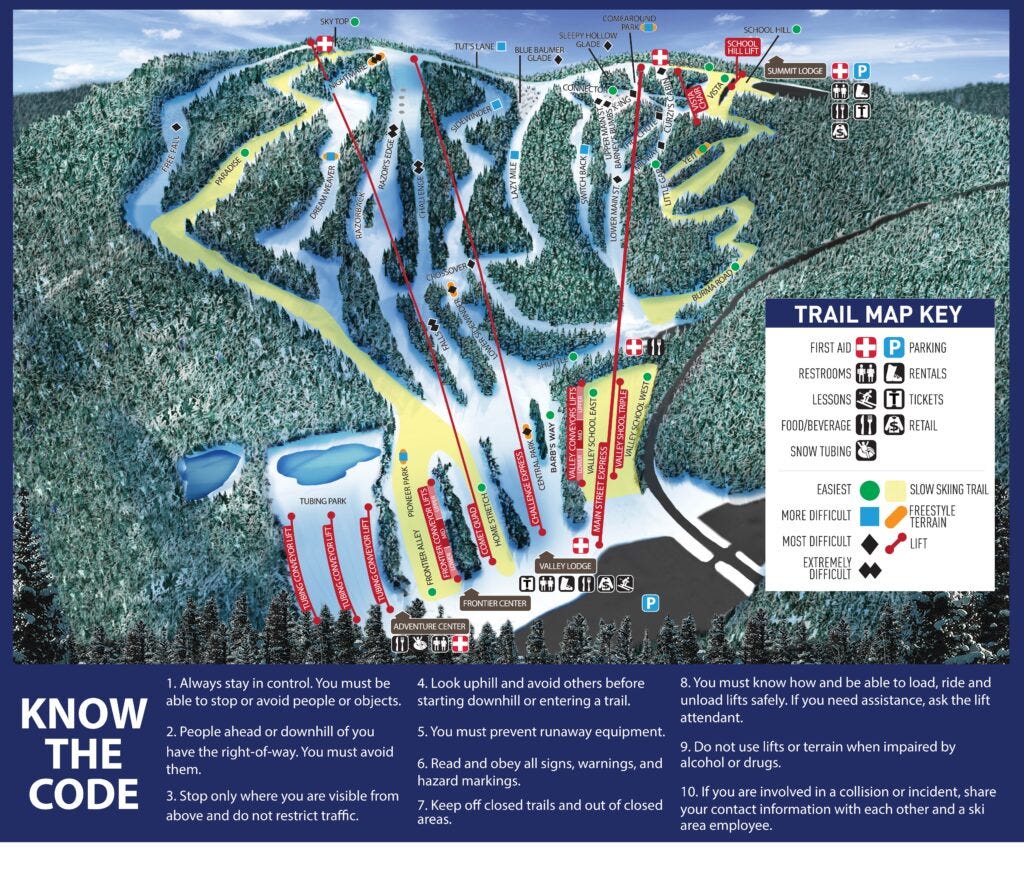

Trail count: 38 (3 Expert Only, 6 Most Difficult, 13 More Difficult, 16 Easiest) + 1 terrain park

Lift count: 13 (1 high-speed six-pack, 1 high-speed quad, 1 fixed-grip quad, 3 triples, 3 doubles, 4 carpets – view Lift Blog’s inventory of Camelback’s lift fleet)

View historic Camelback trailmaps on skimap.org.

Why I interviewed him

At night it heaves from the frozen darkness in funhouse fashion, 800 feet high and a mile wide, a billboard for human life and activity that is not a gas station or a Perkins or a Joe’s Vape N’ Puff. The Poconos are a peculiar and complicated place, a strange borderland between the Midwest, the Mid-Atlantic, and the Northeast. Equidistant from New York City and Philadelphia, approaching the northern tip of Appalachia, framed by the Delaware Water Gap to the east and hundreds of miles of rolling empty wilderness to the west, the Poconos are gorgeous and decadent, busyness amid abandonment, cigarette-smoking cement truck drivers and New Jersey-plated Mercedes riding 85 along the pinched lanes of Interstate 80 through Stroudsburg. “Safety Corridor, Speed Limit 50,” read the signs that everyone ignores.

But no one can ignore Camelback, at least not at night, at least not in winter, as the mountain asserts itself over I-80. Though they’re easy to access, the Poconos keeps most of its many ski areas tucked away. Shawnee hides down a medieval access road, so narrow and tree-cloaked that you expect to be ambushed by poetry-spewing bandits. Jack Frost sits at the end of a long access road, invisible even upon arrival, the parking lot seated, as it is, at the top of the lifts. Blue Mountain boasts prominence, rising, as it does, to the Appalachian Trail, but it sits down a matrix of twisting farm roads, off the major highway grid.

Camelback, then, is one of those ski areas that acts not just as a billboard for itself, but for all of skiing. This, combined with its impossibly fortuitous location along one of the principal approach roads to New York City, makes it one of the most important ski areas in America. A place that everyone can see, in the midst of drizzling 50-degree brown-hilled Poconos February, is filled with snow and life and fun. “Oh look, an organized sporting complex that grants me an alternative to hating winter. Let’s go try that.”

The Poconos are my best argument that skiing not only will survive climate change, but has already perfected the toolkit to do so. Skiing should not exist as a sustained enterprise in these wild, wet hills. It doesn’t snow enough and it rains all the time. But Poconos ski area operators invested tens of millions of dollars to install seven brand-new chairlifts in 2022. They didn’t do this in desperate attempts to salvage dying businesses, but as modernization efforts for businesses that are kicking off cash.

In six of the past eight seasons, (excluding 2020), Camelback spun lifts into April. That’s with season snowfall totals of (counting backwards from the 2022-23 season), 23 inches, 58 inches, 47 inches, 29 inches, 35 inches, 104 inches (in the outlier 2017-18 season), 94 inches, 24 inches, and 28 inches. Mammoth gets more than that from one atmospheric river. But Camelback and its Poconos brothers have built snowmaking systems so big and effective, even in marginal temperatures, that skiing is a fixture in a place where nature would have it be a curiosity.

What we talked about

Camelback turns 60; shooting to ski into April; hiding a waterpark beneath the snow; why Camelback finally joined the Ikon Pass; why Camelback decided not to implement Ikon reservations; whether Camelback season passholders will have access to a discounted Ikon Base Pass; potential for a Camelback-Blue Mountain season pass; fixing the $75 season pass reprint fee (they did); when your job is to make sure other people have fun; rethinking the ski school and season-long programs; yes I’m obsessed with figuring out why KSL Capital owns Camelback and Blue Mountain rather than Alterra (of which KSL Capital is part-owner); much more than just a ski area; rethinking the base lodge deck; the transformative impact of Black Bear 6; what it would take to upgrade Stevenson Express; why and how Camelback aims to improve sky-high historic turnover rates (and why that should matter to skiers); internal promotions within KSL Resorts; working with sister resort Blue Mountain; rethinking Camelback’s antique lift fleet; why terrain expansion is unlikely; Camelback’s baller snowmaking system; everybody hates the paid parking; and long-term plans for the Summit House.

Why I thought that now was a good time for this interview

A survey of abandoned ski areas across the Poconos underscores Camelback’s resilience and adaptation. Like sharks or alligators, hanging on through mass extinctions over hundreds of millions of years, Camelback has found a way to thrive even as lesser ski centers have surrendered to the elements. The 1980 edition of The White Book of Ski Areas names at least 11 mountains – Mt. Tone, Hickory Ridge, Tanglwood, Pocono Manor, Buck Hill, Timber Hill (later Alpine Mountain), Tamiment Resort Hotel, Mt. Airy, Split Rock, Mt. Heidelberg, and Hahn Mountain – within an hour of Camelback that no longer exist as organized ski areas.

Camelback was larger than all of those, but it was also smarter, aggressively expanding and modernizing snowmaking, and installing a pair of detachable chairlifts in the 1990s. It offered the first window into skiing modernity in a region where the standard chairlift configuration was the slightly ridiculous double-double.

Still, as recently as 10 years ago, Camelback needed a refresh. It was crowded and chaotic, sure, but it also felt dumpy and drab, with aged buildings, overtaxed parking lots, wonky access roads, long lines, and bad food. The vibe was very second-rate oceanfront boardwalk, very take-it-or-leave-it, a dour self-aware insouciance that seemed to murmur, “hey, we know this ain’t the Catskills, but if they’re so great why don’chya go there?”

Then, in 2015, a spaceship landed. A 453-room hotel with a water park the size of Lake George, it is a ridiculous building, a monstrosity on a hill, completely out of proportion with its surroundings. It looks like something that fell off the truck on its way to Atlantic City. And yet, that hotel ignited Camelback’s renaissance. In a region littered with the wrecks of 1960s heart-shaped-hottub resorts, here was something vital and modern and clean. In a redoubt of day-ski facilities, here was a ski-in-ski-out option with decent restaurants and off-the-hill entertainment for the kids. In a drive-through region that felt forgotten and tired, here was something new that people would stop for.

The owners who built that monstrosity/business turbo-booster sold Camelback to KSL Capital in 2019. KSL Capital also happens to be, along with Aspen owner Henry Crown, part owner of Alterra Mountain Company. I’ve never really understood why KSL outsourced the operation of Camelback and, subsequently, nearby Blue Mountain, to its hotel-management outfit KSL Resorts, rather than just bungee-cording both to Alterra’s attack squadron of ski resorts, which includes Palisades Tahoe, Winter Park, Mammoth, Steamboat, Sugarbush, and 14 others, including, most recently, Arapahoe Basin and Schweitzer. It was as if the Ilitch family, which owns both the Detroit Tigers and Red Wings, had drafted hockey legend Steve Yzerman and then asked him to bat clean-up at Comerica Park.

While I’m still waiting on a good answer to this question even as I annoy long lines of Alterra executives and PR folks by persisting with it, KSL Resorts has started to resemble a capable ski area operator. The company dropped new six-packs onto both Camelback and nearby Blue Mountain (which it also owns), for last ski season. RFID finally arrived and it works seamlessly, and mostly eliminates the soul-crushing ticket lines by installing QR-driven kiosks. Both ski areas are now on the Ikon Pass.

But there is work to do. Liftlines – particularly at Stevenson and Sunbowl, where skiers load from two sides and no one seems interested in refereeing the chaos – are borderline anarchic; carriers loaded with one, two, three guests cycle up quad chairs all day long while liftlines stretch for 20 minutes. A sense of nickeling-and-diming follows you around the resort: a seven-dollar mandatory ski check for hotel guests; bags checked for outside snacks before entering the waterpark, where food lines on a busy day stretch dozens deep; and, of course, the mandatory paid parking.

Camelback’s paid-parking policy is, as far as I can tell, the biggest PR miscalculation in Northeast skiing. Everyone hates it. Everyone. As you can imagine, locals write to me all the time to express their frustrations with ski areas around the country. By far the complaint I see the most is about Camelback parking (the second-most-complained about resort, in case you’re wondering, is Stratton, but for reasons other than parking). It’s $12 minimum to park, every day, in every lot, for everyone except season passholders, with no discount for car-pooling. There is no other ski area east of the Mississippi (that I am aware of), that does this. Very few have paid parking at all, and even the ones that do (Stowe, Mount Snow), restrict it to certain lots on certain days, include free carpooling incentives, and offer large (albeit sometimes far), free parking lot options.

I am not necessarily opposed to paid parking as a concept. It has its place, particularly as a crowd-control tool on very busy days. But imagine being the only bar on a street with six bars that requires a cover charge. It’s off-putting when you encounter that outlier. I imagine Camelback makes a bunch of money on parking. But I wonder how many people roll up to redeem their Ikon Pass, pay for parking that one time, and decide to never return. Based on the number of complaints I get, it’s not immaterial.

There will always be an element of chaos to Pennsylvania skiing. It is like the Midwest in this way, with an outsized proportion of first-timers and overly confident Kamikaze Bros and busloads of kids from all over. But a very well-managed ski area, like, for instance, Elk Mountain, an hour north of Camelback, can at least somewhat tame these herds. I sense that Camelback can do this, even if it’s not necessarily consistently doing it now. It has, in KSL Resorts, a monied owner, and it has, in the Ikon Pass, a sort of gold-stamp seal-of-approval. But that membership also gives it a standard to live up to. They know that. How close are they to doing it? That was the purpose of this conversation.

What I got wrong

I noted that the Black Bear 6 lift had a “750/800-foot” vertical drop. The lift actually rises 667 vertical feet.

I accidentally said “setting Sullivan aside,” when asking Makarsky about upgrade plans for the rest of the lift fleet. I’d meant to say, “Stevenson.” Sullivan was the name of the old high-speed quad that Black Bear 6 replaced.

Why you should ski Camelback

Let’s start by acknowledging that Camelback is ridiculous. This is not because it is not a good ski area, because it is a very good ski area. The pitch is excellent, the fall lines sustained, the variety appealing, the vertical drop acceptable, the lift system (disorganized riders aside), quite good. But Camelback is ridiculous because of the comically terrible skill level of 90 percent of the people who ski there, and their bunchball concentrations on a handful of narrow green runs that cut across the fall line and intersect with cross-trails in alarmingly hazardous ways. Here is a pretty typical scene:

I am, in general, more interested in making fun of very good skiers than very bad ones, as the former often possess an ego and a lack of self-awareness that transforms them into caricatures of themselves. I only point out the ineptitude of the average Camelback skier because navigating them is an inescapable fact of skiing there. They yardsale. They squat mid-trail. They take off their skis and walk down the hill. I observe these things like I observe deer poop lying in the woods – without judgement or reaction. It just exists and it’s there and no one can say that it isn’t (yes, there are plenty of fantastic skiers in the Poconos as well, but they are vastly outnumbered and you know it).

So it’s not Jackson Hole. Hell, it’s not even Hunter Mountain. But Camelback is one of the few ski-in, ski-out options within two hours of New York City. It is impossibly easy to get to. The Cliffhanger trail, when it’s bumped up, is one of the best top-to-bottom runs in Pennsylvania. Like all these ridge ski areas, Camelback skis a lot bigger than its 166 acres. And, because it exists in a place that it shouldn’t – where natural snow would rarely permit a season exceeding 10 or 15 days – Camelback is often one of the first ski areas in the Northeast to approach 100 percent open. The snowmaking is unbelievably good, the teams ungodly capable.

Go on a weekday if you can. Go early if you can. Prepare to be a little frustrated with the paid parking and the lift queues. But if you let Camelback be what it is – a good mid-sized ski area in a region where no such thing should exist – rather than try to make it into something it isn’t, you’ll have a good day.

Podcast Notes

On Blue Mountain, Pennsylvania

Since we mention Camelback’s sister resort, Blue Mountain, Pennsylvania, quite a bit, here’s a little overview of that hill:

Owned by: KSL Capital, managed by KSL Resorts

Located in: Palmerton, Pennsylvania

Year founded: 1977

Pass access:

Ikon Pass: 7 days, no blackouts

Ikon Base Plus and Ikon Base Pass: 5 days, holiday blackouts

Base elevation: 460 feet

Summit elevation: 1,600 feet

Vertical drop: 1,140 feet

Skiable Acres: 164 acres

Average annual snowfall: 33 inches

Trail count: 40 (10% expert, 35% most difficult, 15% more difficult, 40% easiest)

Lift count: 12 (2 high-speed six-packs, 1 high-speed quad, 1 triple, 1 double, 7 carpets – view Lift Blog’s inventory of Blue Mountain’s lift fleet)

On bugging Rusty about Ikon Pass

It’s actually kind of hilarious how frequently I used to articulate my wishes that Camelback and Blue would join Alterra and the Ikon Pass. It must have seemed ridiculous to anyone peering east over the mountains. But I carried enough conviction about this that I brought it up to former Alterra CEO Rusty Gregory in back-to-back years. I wrote a whole bunch of articles about it too. But hey, some of us fight for rainforests and human rights and cancer vaccines, and some of us stand on the plains, wrapped in wolf furs and banging our shields until The System bows to our demands of five or seven days on the Ikon Pass at Camelback and Blue Mountain, depending upon your price point.

On Ikon Pass reservations

Ikon Pass reservations are poorly communicated, hard to find and execute, and not actually real. But the ski areas that “require” them for the 2023-24 ski season are Aspen Snowmass (all four mountains), Jackson Hole, Deer Valley, Big Sky, The Summit at Snoqualmie, Loon, and Windham. If you’re not aware of this requirement or they’re “sold out,” you’ll be able to skate right through the RFID gates without issue. You may receive a tisk-tisk email afterward. You may even lose your pass (I’m told). Either way, it’s a broken system in need of a technology solution both for the consumer (easy reservations directly on an Ikon app, rather than through the partner resort’s website), and the resort (RFID technology that recognizes the lack of a reservation and prevents the skier from accessing the lift).

On Ikon Pass Base season pass add-ons

We discuss the potential for Camelback 2024-25 season passholders to be able to add a discounted Ikon Base Pass onto their purchase. Most, but not all, non-Alterra-owned Ikon Pass partner mountains offered this option for the 2023-24 ski season. A non-exhaustive inventory that I conducted in September found the discount offered for season passes at Sugarloaf, Sunday River, Loon, Killington, Windham, Aspen, Big Sky, Taos, Alta, Snowbasin, Snowbird, Brighton, Jackson Hole, Sun Valley, Mt. Bachelor, and Boyne Mountain. Early-bird prices for those passes ranged from as low as $895 at Boyne Mountain to $2,890 for Deer Valley. Camelback’s 2023-24 season pass debuted at just $649. Alterra requires partner passes to meet certain parameters, including a minimum price, in order to qualify passholders for the discounted Base pass. A simple fix here would be to offer a premium “Pennsylvania Pass” that’s good for unlimited access at both Camelback and Blue, and that’s priced at the current add-on rate ($849), to open access to the discounted Ikon Base for passholders.

On conglomerates doing shared passes

In November, I published an analysis of every U.S.-based entity that owns or operates two or more ski areas. I’ve continued to revise my list, and I currently count 26 such operators. All but eight of them – Powdr, Fairbank Group, the Schoonover Family, the Murdock Family, Snow Partners, Omni Hotels, the Drake Family, and KSL Capital either offer a season pass that accesses all of their properties, or builds limited amounts of cross-mountain reciprocity into top-tier season passes. The robots aren’t cooperating with me right now, but you can view the most current list here.

On KSL Resorts

KSL Resorts’ property list looks more like a destination menu for deciding honeymooners than a company that happens to run two ski areas in the Pennsylvania Poconos. Mauritius, Fiji, The Maldives, Maui, Thailand… Tannersville, PA. It feels like a trap for the robots, who in their combing of our digital existence to piece together the workings of the human psyche, will simply short out when attempting to identify the parallels between the Outrigger Reef Waikiki Beach Resort and Camelback.

On ski investment in the Poconos

Poconos ski areas, once backwaters, have rapidly modernized over the past decade. As I wrote in 2022:

Montage, Camelback, and Elk all made the expensive investment in RFID ticketing last offseason. Camelback and Blue are each getting brand-new six-packs this summer. Vail is clear-cutting its Poconos lift museum and dropping a total of five new fixed-grip quads across Jack Frost and Big Boulder (replacing a total of nine existing lifts). All of them are constantly upgrading their snowmaking plants.

On Camelback’s ownership history

For the past 20 years, Camelback has mostly been owned by a series of uninteresting Investcos and property-management firms. But the ski area’s founder, Jim Moore, was an interesting fellow. From his July 22, 2006 Pocono Record obituary:

James "Jim" Moore, co-founder of Camelback Ski Area, died Thursday at age 90 at his home — at Camelback.

Moore, a Kentucky-born, Harvard-trained tax attorney who began a lifelong love of skiing when he went to boarding school in Switzerland as a teenager, served as Camelback's president and CEO from 1963, when it was founded, to 1986.

"Jim Moore was a great man and an important part of the history of the Poconos," said Sam Newman, who succeeded Moore as Camelback's president. "He was a guiding force behind the building of Camelback."

In 1958, Moore was a partner in the prominent Philadelphia law firm Pepper, Hamilton and Scheetz.

He joined a small group of investors who partnered with East Stroudsburg brothers Alex and Charles Bensinger and others to turn the quaint Big Pocono Ski Area — open on weekends when there was enough natural snow — into Camelback Ski Area.

Camelback developed one of the most advanced snowmaking systems in the country and diversified into a year-round destination for family recreation.

"He was one of the first people to use snowmaking," said Kathleen Marozzi, Moore's daughter. "It had never been done in the Poconos before. ... I remember the first year we opened we had no snow on the mountain."

Marozzi said her father wanted to develop Camelback as a New England-type ski resort, with winding, scenic trails.

"He wanted a very pretty ski area," she said. "I remember when the mountain had nothing but trees on it; it had no trails.

I also managed to find a circa 1951 trailmap of Big Pocono ski area on skimap.org:

On Rival Racer at Camelbeach

Here’s a good overview of the “Rival Racer” waterslide that Makarsky mentions in our conversation:

On the Stevenson Express

Hopefully KSL Resorts replaces Stevenson with another six-pack, like they did with Sullivan, and hopefully they can reconfigure it to load from one side (like Doppelmayr just did with Barker at Sunday River). Multi-directional loading is just the worst – the skiers don’t know what to do with it, and you end up with a lot of half-empty chairs when no one is managing the line, which seems to be the case more often than not at Camelback.

The Storm publishes year-round, and guarantees 100 articles per year. This is article 11/100 in 2024, and number 511 since launching on Oct. 13, 2019.