Squint Hard: Skiing’s Future Is Unfolding Now, In The Poconos

Technology has already saved skiing in one of America’s most snow-poor mountain regions

In which we will attempt to delay the apocalypse

Westbound on Interstate 80, the Poconos erupt over the New Jersey-Pennsylvania border, the twin prominences of the Delaware Water Gap soaring 800 feet off the river below.

Through this keyhole travelers enter one of the densest concentrations of ski areas in North America. Turn north off the first exit for gentle Shawnee, 700 vertical feet of golf course-grade inclines. Keep straight for Camelback, an 800-foot north-facing ridge stretching a mile along the highway. Another 15 miles west sit Vail’s twin bumps of Jack Frost, a 600-foot upside-downer, and Big Boulder, a onetime great terrain park that’s becoming something else – no one’s sure just what yet – under Broomfield’s supervision. Seventeen miles south of Big Boulder is Blue Mountain, where twin detachables rise nearly 1,100 vertical feet. The same distance north from Jack Frost sits Montage, the resurgent thousand-footer, night lights popping like fireworks off the shoulder of Interstate 81. Then it’s 26 more miles to Elk, technically out of the Poconos but the state’s finest ski area, a thousand feet of fall-lines, bumps, and trails winding through the trees. Scattered amongst this constellation are a dozen little-known bumps attached to a resort or a housing development, along with 650-foot Big Bear at Masthope Mountain.

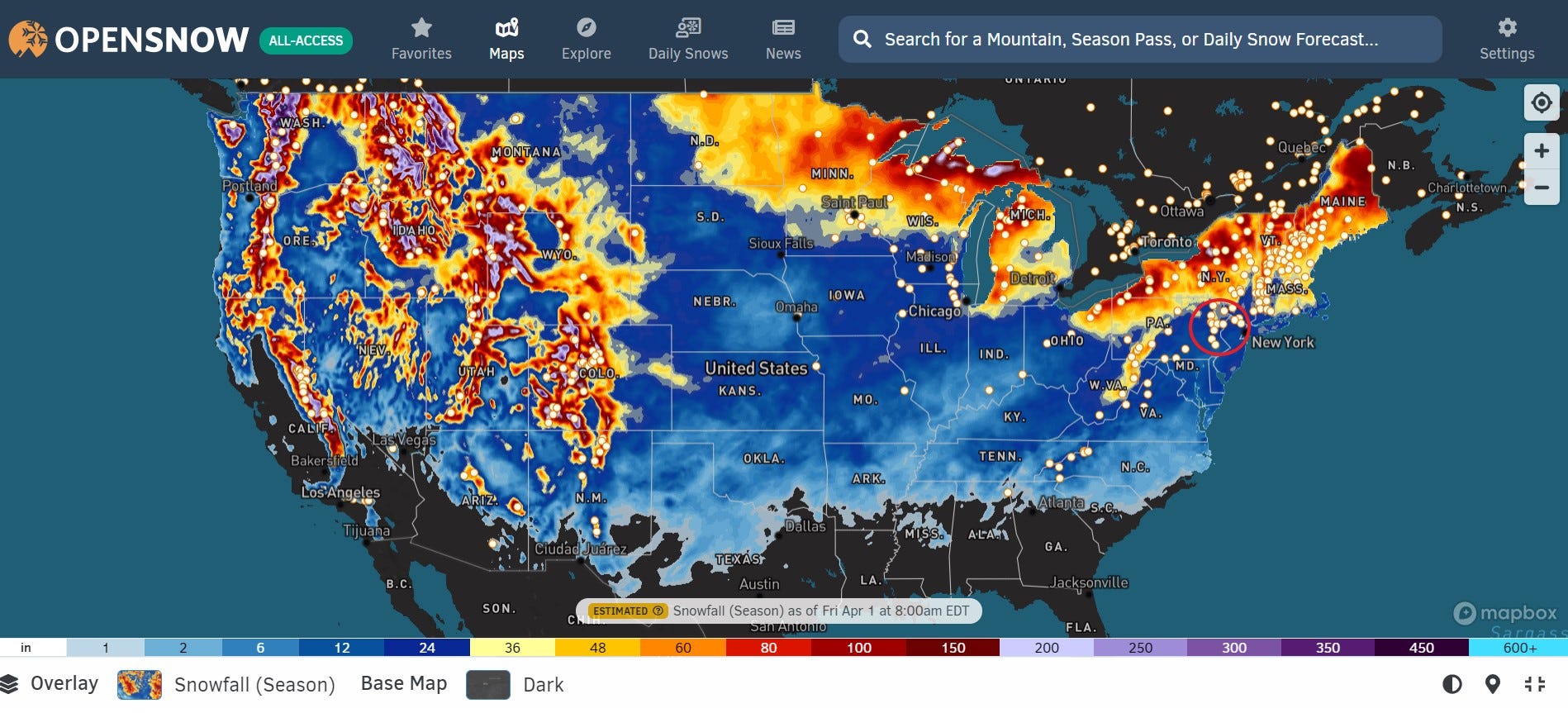

Northeast Pennsylvania has just about everything necessary to fuel a successful ski operation: plenty of hills, plenty of people, plenty of water, plenty of cold. What it does not have much of, most winters, is snow. Each dot on the map below represents a ski area. The Poconos, unique among mountain ski regions, sit in a snow desert, scoring totals equal to the Vast Empty from Ohio west across Kansas and Nebraska:

This year was no anomaly. This National Weather Service map documenting snowfall for the decade of 2010 through 2019 shows the Poconos collecting approximately the same total accumulations as Detroit or New York City. Occasional dumps, mostly blah:

The Poconos have other problems. Constant freeze-thaw cycles quickly trash whatever natural snow falls. In spite of plenty of low overnight temps to blow snow, the rain comes all year long: an average of three to four inches falls from December through March. The snowpack is never really safe.

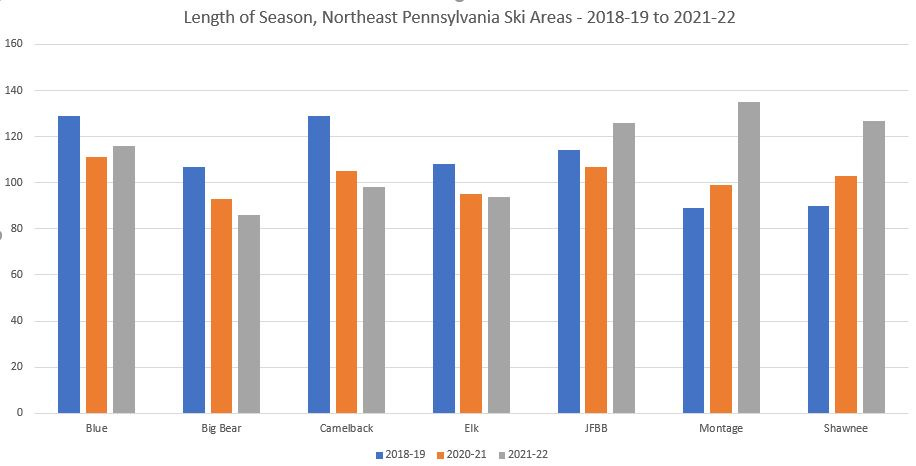

And yet. The region’s resorts consistently post 100-plus-day operating seasons – much more, if they can score a November cold snap. While all of northeastern Pennsylvania’s major ski areas finished below the NSAA’s recorded average of 112 operating days during the 2020-21 winter, a peak back at the past several seasons documents nearly twice as many 100-plus-day campaigns as those with fewer than 100 days:

How is this possible? Mainstream news reports exploring skiing in the era of climate change often oversimplify the dynamic between man and Mother Nature, exasperating a truth – long-term weather patterns are changing – with an assumption: we are powerless to adapt. This was one of the major flaws of a widely shared NPR report earlier this week that positioned skiing as teetering on the verge of collapse:

This last winter was supposed to be a post-Covid rebound for America's $50 billion ski industry. But persistent drought linked to climate change, labor shortages and frustrated customers stuck in traffic and in long lift lines has made getaways less attractive.

Climate anxiety is also focusing attention on the business model of resorts, which have increasingly relied on a more luxury clientele who often have to drive long distances burning fossil fuels or fly in on private jets.

This article rests on several flawed assumptions. Among them:

“This winter was supposed to be a post-Covid rebound…” No it wasn’t. The post-Covid rebound happened last winter, where the social-distancing-inspired outdoor boom drove 59 million skier visits, the fifth-best season on record, according to the National Ski Areas Association. Seventy-eight percent of ski area operators told the NSAA last year that the season had exceeded their expectations.

“…has made getaways less attractive.” According to… what? Vail documented increased season-to-date skier visits during its last earnings call. Yes, the season started late in several regions, but there is no indication that a material number of skiers have opted out of trips this year.

“…the business model of resorts, which have increasingly relied on a more luxury clientele.” Yes, that’s what Vail had in mind when they started stuffing Epic Passes into boxes of Cracker Jacks. Skiing for frequent skiers has never been cheaper. The reporter’s main source for this conclusion appears to be a local columnist who was grumpy about private planes lined up on the tarmac of Aspen’s airport.

That’s breaking down three sentences. The article is filled with false conclusions backed up with very little data. But this is the sort of fragmented logic that much of the non-skiing world applies to the future of skiing: well damnit if it’s raining in February in Michigan then how on earth can we expect to be skiing in Colorado in 2082?

Which takes us back to Northeast Pennsylvania, which looks an awful lot like the worst-case-scenario futureworlds often conjured in such articles as the setting in which skiing will curdle and die. The Poconos is not supposed to be a place where industrial-scale skiing makes sense. In some ways, it doesn’t. Conditions are often atrocious. The rain, the refreezes, the sheer bullrun of horrid skiers – having skiing is not the same thing as having great skiing. But the mountains lend themselves to snowsports, with long runs and decent fall-lines, and so generations of operators have figured out how to hack a decent season out of impossible-seeming circumstances.

The cornerstone is snowmaking: Blue, Camelback, Jack Frost, Big Boulder, Montage, and Shawnee all have 100 percent coverage. Because of this, they are often among the first ski areas in the Northeast to fully open, beating out the colder and snowier resorts in New England (many of which, to be fair, have far more terrain to cover).

“Well no kidding Bro thanks for that amazing insight. But you know they have water problems out west. The owner of Beaver Mountain just told you on your own podcast that they had no idea where the water would come from if they decided to put in snowmaking.”

Oh hi there Cynical-About-Everything Bro, I was just thinking about you. Yes, that’s true, but Mr. Seeholzer also told me that some kind of system was inevitable once they figured out that engineering problem.

“Oh, what’s he going to do? Assemble his beavers to chop down the forest and dam a pond on the mountaintop? Run a pipeline to Salt Lake? Order 100,000 loaded Super Soakers from Amazon?”

You know Cynical-About-Everything Bro, you remind me of the nitwit that just commented on my April Fool’s post about snowboarding being allowed at Mad River Glen that if I “had a clue” about how the single chair operated, I wouldn’t think the ban was so, as I dubbed it, “silly.” But you know, MRG has been using that excuse about the wonky summit unload for decades, and it’s a little bit stupid: I think that the society that invented the internet and space travel could probably manage the job of re-engineering a chairlift so that snowboarders could safely exit.

“Oh, yes, let’s just throw all of all our sacred traditions in the garbage.”

You know I really don’t like you. My point here is that the ski industry has already assembled a large base of technological know-how to help grapple with whatever climate crisis may be forthcoming. The Pennsylvania dozen are not struggling ski areas, barely hacking out an existence in their marginal climate. Montage, Camelback, and Elk all made the expensive investment in RFID ticketing last offseason. Camelback and Blue are each getting brand-new six-packs this summer. Vail is clear-cutting its Poconos lift museum and dropping a total of five new fixed-grip quads across Jack Frost and Big Boulder (replacing a total of nine existing lifts). All of them are constantly upgrading their snowmaking plants.

Such snowmaking expertise is widespread in the Northeast, even where its less existentially urgent. Massachusetts-based snowsports columnist Shaun Sutner broke the regional firepower down in his season-ending column this week:

The ski season isn’t over yet.

More than enough snow is still on the ground to keep skiing and snowboarding well into April at more than a dozen northern New England ski areas, including Mount Snow, Stratton, Okemo, Killington, Sugarbush, Stowe, Smuggler’s Notch, Jay Peak, Burke, Waterville Valley, Loon, Cannon, Bretton Woods, Saddleback, Sunday River and Sugarloaf.

As usual, Killington and Sunday River — which along with Mount Snow possess the most powerful snowmaking systems in the East — will shoot for May and probably achieve it. …

How all this is possible at the end of a remarkably natural snow-less 2020-21 season is a testament to the modern snowmaking technology that is critical to opening as early as possible in the fall, extending the season far into spring, building snowpack during dry spells, and recovering quickly after rainstorms.

That snowmaking and snow grooming firepower and expertise is also what kept Wachusett Mountain, whose scheduled closing day is this Sunday, April 3, open all season with the most consistently good skiing and riding conditions anywhere in the East. Pats Peak and a few other smaller areas also excelled during this challenging season.

Wachusett and some other smaller areas are every bit the equal of the bigger northern resorts in terms of making and grooming snow, only on a smaller scale.

When cold weather snowmaking windows open, however briefly, southern New England ski areas like Wachusett, Jiminy Peak and even tiny Ski Ward are able to quickly blanket broad swaths of terrain with machine-made snow that is able to survive dramatic warmups and even heavy rain.

None of this is meant to minimize climate change, or to suggest that serious disruptions are not on a collision course with U.S. skiing. A future version of the Poconos may well be one in which no amount of innovation can produce a viable ski season (though technology already exists to produce snow in above-freezing temperatures). Northeast Pennsylvania has never been an easy place to run a ski area, and the hills are already littered with at least a dozen lost resorts. But if you want to see what a snow-starved, rain-intensive, variable-temperature but viable future ski world looks like, the Poconos is the place to start.

Below the subscriber jump: someone buys the long-lost (but remarkably intact) Brodie ski area; Snow Valley, Vermont goes up for sale; we finally see the new gondola line for Timberline Lodge; Jackson Hole solves the crowding problem; a second Utah ski area steps up against Snowbird to offer skiing into May; and why is Tahoe gem Homewood getting crushed amid the indie ski boom?