America’s Hidden Mega Ski Pass: 3 Days Each at 48 Mountains, Plus a Season Pass, for $299

Ski Cooper assembles the strongest coast-to-coast reciprocal lift ticket plan in U.S. skiing

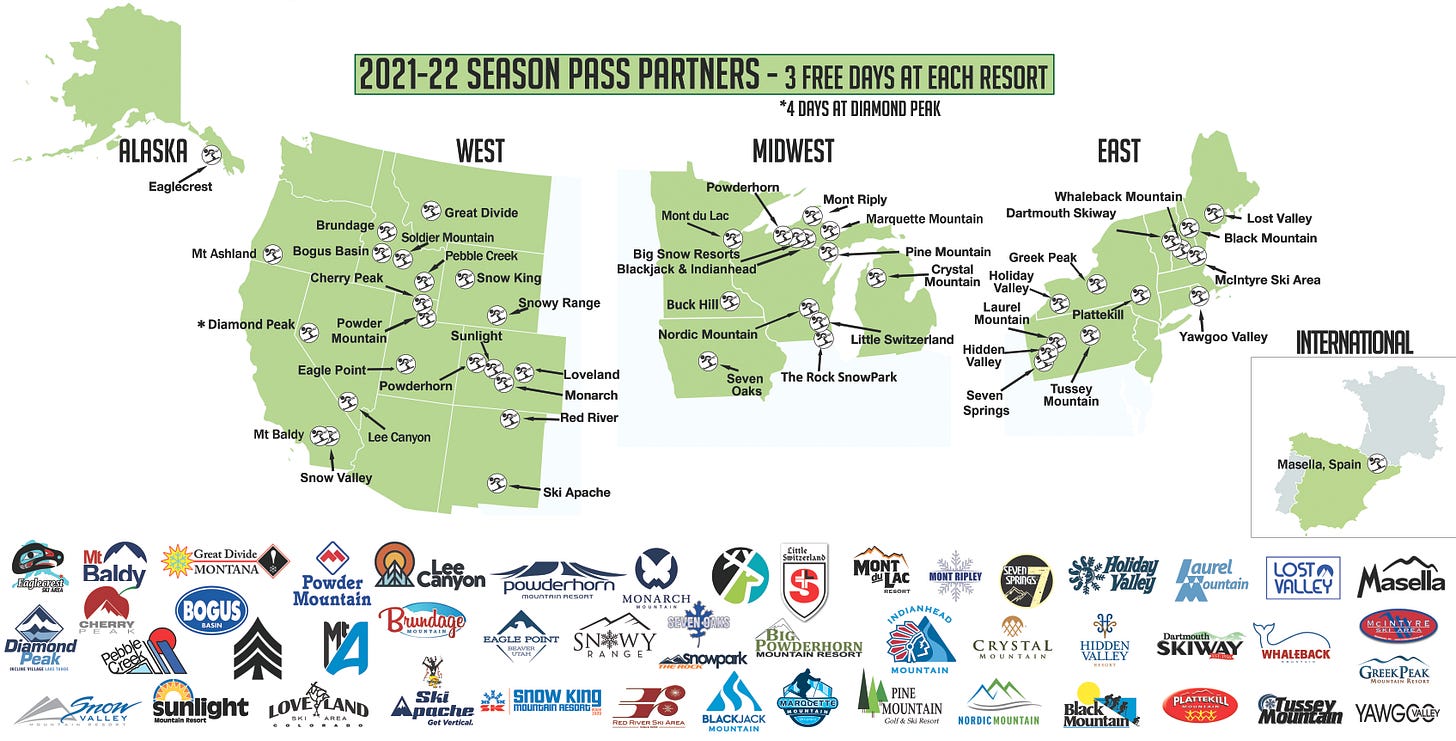

The map is beautiful. Simple and clear, it lays out Ski Cooper’s nationwide regiment of partners. Buy the mountain’s $299 ($249 for renewing passholders) season pass, and get three days of skiing at each:

There are 48 partners and almost no blackouts. It is the largest and most straightforward reciprocal lift ticket coalition in North America.

Ski Cooper’s sprawling season pass access is also the logical end state of a lift-served skiing universe increasingly defined by the Epic and Ikon passes, with their dazzling collections of poke-through-the-clouds resorts, relentless marketing, and fantastically achievable price points. Small ski areas, sitting alone, have a harder story to tell and far fewer resources to do it. Band together, and the story gets more interesting. And Ski Cooper is telling one of the best stories in skiing.

The shortest kid on the basketball team shocks everyone with a dunk from the free-throw line

Ski Cooper has plenty going for it: a base elevation above 10,000 feet, guaranteeing both frequent and long-lasting snow; 470 acres of varied terrain; a low-key atmosphere for skiers burned out on megresorts; a mountain-management philosophy that eschews over-grooming and values snow in its natural state; and an impressive Cat-skiing operation. It’s a nice little top-of-the-world ski area:

Still, Ski Cooper drew one of the short straws in U.S. skiing. While it’s tucked off U.S. 24 just half an hour south of Interstate 70 - American skiing’s Main Street - it’s seated less than an hour from a half dozen titanic Epic and Ikon resorts: Copper Mountain, Vail, Beaver Creek, Keystone, Breckenridge, and Arapahoe Basin. Its 470 acres would be substantial in most places, but is less than 1/10th Vail Mountain’s skiable terrain. Ski Cooper’s claimed annual snowfall of 260 inches is plenty, but it’s several feet fewer than Vail’s 354 inches and Beaver Creek’s 325. The mountain’s two chairlifts are a combined 86 years old, and the ski area has no snowmaking (General Manager Dan Torsell emphasizes this isn’t needed – Ski Cooper typically has enough snowpack to make it to June, should they choose to). When the state’s megaresorts rolled up into Team Epic and Team Ikon over the past several years, they left Ski Cooper standing on the sidelines, waiting to be picked.

Like skiing’s Spud Webb, the 5’7” leapfrog who won the 1986 NBA Slam Dunk Contest over the towering Dominique Wilkins, Ski Cooper shocked everyone with the ski area equivalent of a reverse double-pump jam: it built a nationwide partner network as large – if not as substantial – as the Resortasaurus conglomerates, all priced not much higher than a one-day peak season lift ticket at its corporate neighbors.

Many Western ski areas have built substantial reciprocal partner networks, of course. The Powder Alliance unites a dozen of them, plus two large Alberta ski areas and one in Japan – season passholders at any of them get three lift tickets to each of the others. Loveland is part of this coalition, and throws tickets to another 16 ski areas on top of it. Ski Cooper partner Monarch has put together around two dozen reciprocal deals. And Sunlight, Colorado leads the 14-member reciprocal Freedom Pass coalition – which Cooper is a part of – and has locked in additional partnerships with more than a dozen ski areas. These examples are typical of mid-sized western ski areas, where very few independents – Wolf Creek, Colorado is one of the few – truly stand alone.

But three characteristics make Ski Cooper’s pass stand out in this powdery gameshow: the low pass price, the breadth of the partner network, and the consistency of the reciprocal benefit.

First, price: almost anyone can scrape together $299 for a season pass. Select other ski areas do meet Cooper on price – Powderhorn, Colorado, offers a (long-gone for next season) $299 “Mission Affordable” early-bird pass price. But most Western mountains set their prices much higher (even if these passes are inexpensive by Northeast standards): Monarch’s pass is $459 ($439 renewal); Brundage, Idaho is $599; Sierra-at-Tahoe, California is $549.

All of those passes include substantial partner benefits. But none are as deep or as broad as Cooper’s. Most western ski areas offer few, if any, options in the Midwest or Northeast. Cooper passholders can access access 13 ski areas in the Midwest and 13 in the Northeast. Twenty-one others are scattered across the West (one is in Spain). The only substantial ski markets without a Ski Cooper partner are Washington State and the Southeast. The offerings are so extensive, in fact, that I added Ski Cooper’s season pass as a regional pass in my Northeast season pass tracker. And why not? Only the Epic and Indy passes equal or surpass it in number of Northeast partners.

The point of these far-flung partnerships is less to drive the Cooper diaspora east than to entice vacationing Midwestern and New England skiers to the Rockies.

“I look at it like a free, self-sustaining marketing and advertising program,” Torsell told me in a phone interview last week. “We're not actively trying to get people from other parts of the country to necessarily buy our pass. What we're trying to do is get them to come here, because if they have their Whaleback pass and they come here with their family for three days, a couple of things happen. Yeah, they're going to buy burgers and beer and fries for the kids, and maybe take a lesson to rent some skis if they're coming across the country. … But from an exposure standpoint, which is probably more important, they're going to go home and they're going to tell people, ‘Hey, you know, that place is really cool.’

“Still, to this day, I think word of mouth is huge. Anecdotally, I can tell you, people come here from all over the country. I talk to a lot of them. I ski all the time, and I ask them, ‘How come you're here?’ ‘Well, my brother-in-law and family visited and they had a great time, so we felt we should take advantage of it. We could afford it because of your pricing, so here we are.’ I look at the whole exposure thing, rather than what it's creating in terms pass sales across the country.”

What really sets Ski Cooper’s reciprocal pass program apart, however, is its consistency: three no-blackout days at each partner. This is uncommon. And welcome. Decoding blackout-date grids on many mountain’s partner pages is like trying to read hieroglyphics. “Three free lift tickets! Valid between Easter and Thanksgiving. Saturdays excepted. Not valid if you are wearing pants or were born in July or between the years of 1932 and 2016. U.S. residents excluded. Must be driving a tank and carrying a pet racoon. Program cancelled when on-mountain snow depth exceeds one inch.”

Ski Cooper somehow wrangled 46 of its 48 partners into the kind of simple and consistent plan that only Vail and Alterra have otherwise had the leverage to achieve across partner resorts.

“We couldn't have different partners offering a bunch of different custom benefits in terms of blackout dates and what type of reciprocal deal we would have,” Torsell said. “We just tried to work with folks, and we came up with a little agreement that's pretty standard: three days, each way. If somebody is really adamant about blackout days, we pretty much steer away from them. I’ve got people from 1,500 miles away going, ‘Oh, we gotta have blackout days. We can't afford to have your people coming on weekends.’ And I'm going well, ‘how freaking many of my people are going to XYZ in frickin’ California on a weekend?’”

Torsell credits Dana Johnson, Ski Cooper’s tireless director of marketing and sales, for hammering out such a consistent platform. “She's done a fantastic job of dealing and negotiating,” he said.

Only Diamond Peak, Nevada, where a peak-day lift ticket ran $124 last season, and Brundage, Idaho have blackout exceptions, all around the peak December, January, and February holidays. Diamond Peak somewhat mitigates this with a fourth day for Cooper passholders. Idaho-bound Cooper skiers locked out of Brundage can simply hit nearby Bogus Basin, which has a similar vertical drop and skiable acreage.

What Ski Cooper has built is remarkable. It may be the best mid-sized mountain season pass in America for sheer value and breadth of access. And while it won’t replace an Epic or Ikon pass for most skiers, it’s an affordable complement for the rambling-minded or those looking to escape high-season lift lines at Vail.

“I don't necessarily look at our partner program as a response to or a reaction to Epic or Ikon, because probably it’s a slightly different market segment that we're dealing with,” said Torsell. “I guess it’s a positive unintended consequence that we are getting a number of people – not tons – but we're seeing more visitation and pass purchasing from folks across the hill, as I like to say, from the big resorts. They will buy a Ski Cooper pass as a second pass as a convenience. If it's busy there, they'll come here.”

Ski Cooper may be the Indy Pass’ closest competitor

A few weeks back, I speculated that the U.S. had enough unclaimed independent resorts that a fifth national ski pass – in addition to Epic, Ikon, Mountain Collective, and Indy – was inevitable. I offered Mountain Capital Partners’ Power Pass as the best existing base for an indie-focused entry seated between the Indy and Epic/Ikon price points, a hybrid unlimited/limited-day-partners pass in Ikon’s mode built atop Indy-style round-the-bend mountains with a shortage of fur coats and private helicopters.

But we already have a fifth national pass, and it is Ski Cooper’s. In its price point, access model, and geographic breadth, it competes most closely with the Indy Pass. In fact, the passes share 15 partners*. Both have advantages, both for skiers and ski areas, and comparing them side-by-side is a worthwhile exercise. Let’s look at skiers first:

Price and access

Indy added more than a dozen mountains over the past year – many of them true destination resorts such as Jay Peak, Vermont and Tamarack, Idaho – and boosted prices significantly (and justifiably) – for its 2021-22 pass suite as a result. The $199 base pass jumped to $279 ($119 for kids), from $199 ($99 for kids) last season, and introduced substantially more blackouts. The blackout tiers are numerous and somewhat confusing. Skiers can avoid all of them with the $379 Indy+ Pass.

Cooper’s pass structure is simpler: $299 for adults, $149 for kids 6-14. Renewing passholders pay just $249 ($99 for kids). The partner benefits don’t cost any extra. So the no-blackout version of the Indy Pass currently runs $80 higher than Ski Cooper’s.

It’s worth underscoring that Indy Pass holders get two days at each partner mountain while Cooper passholders receive three. With Indy’s 68 current partners and Cooper’s 48 (both are likely to add more before the season begins), that adds up to 136 Indy days and 144 Cooper days. That addition is mostly an academic exercise – maxing out either pass is improbable. But since the Cooper pass is an unlimited home-mountain pass, it has a hard-wired advantage over Indy in sheer access.

“When I look at the Indy pass, I think it's a really cool concept, and when [Indy Pass founder] Doug [Fish] was here a couple of years ago visiting me and we sat down and really looked at it, I thought, ‘that's really creative and I like it,’” said Torsell. “But there is an unrelated cost with that. If I buy an Indy pass, and all I want to do is ski the country, I think that's a great fricking deal. But I don't have a home area pass. The people that buy the Cooper pass, they have unlimited skiing here. And when we had 55 partners last year, times three, that's 165 days potential now obviously at our partners, plus the 130-plus days we're open. That's pretty interesting and compelling.”

Passholders at any Indy Pass mountain can, however, add on an Indy Pass for substantially less than the standalone price: the add-on base version is $189 for adults and $89 for kids; the add-on Plus pass is $289 for adults and $139 for kids.

Both passes have price jumps scheduled. Ski Cooper’s pass will increase to $399 ($199 for kids) on Aug. 1, and $499 ($249 for kids) on Oct. 1. Indy will increase to $299 on Sept. 1 ($129 kids, $399 Indy+, $179 Indy+ kids) and $329 ($139 kids, $429 Indy+, $189 Indy+ kids) on Dec. 1.

This is the budget version of choosing between Epic and Ikon – both have enormous strengths. Both have shortcomings. Which is the best choice for you probably depends upon where you live and individual taste. It would be hard to choose a bad option here, but a region-by-region breakdown helps distill the specific strengths of each:

Northeast

It’s an Indy Pass rout in New England. Reciprocal pass partnerships are rare in New England, and most mountains that have tried them abandoned them in short order. The most high-profile – a Jay Peak-Saddleback two-day exchange – evaporated after both joined the Indy Pass. Magic and Bolton Valley left the Freedom Pass after one season with Indy. Indy now has a dozen partners across Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, including some bangers like Cannon and Waterville Valley. Ski Cooper has half that many New England partners, most of them community bumps like McIntyre, New Hampshire and Lost Valley, Maine.

Things even out in Pennsylvania and New York. Both passes claim the ever-improving Greek Peak, New York. Ski Cooper passholders can access Holiday Valley, the crown jewel of Western New York and a beneficiary of the Lake Eerie snowbelt, and the rowdy and uncrowded Plattekill in the Catskills. With this excellent trio – all easily among the state’s top 10 ski areas – Ski Cooper edges out Indy’s New York offering of Swain (close to Holiday Valley but not as large), Snow Ridge (excellent but remote), and steadily-improving-and-finally-up-to-date-but-smaller West Mountain.

Pennsylvania goes handily to Cooper. Indy passholders get two days each at Blue Knob and Shawnee. The former is big and fun but rarely fully open due to under-investment in snowmaking. Shawnee is prototypical Poconos chaos on weekends. But Cooper forged a deal for three tickets each at the jointly owned trio of Seven Springs, Laurel, and Hidden Valley – the top ski areas in Western Pennsylvania. Cooper skiers can also access little Tussey Mountain in the middle of the state.

Midwest

Indy again holds a substantial edge in this region, with one important exception: Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Here Ski Cooper has locked down deals with a half-dozen very nice ski areas to Indy’s two (and Cooper passholders can access both of them). If you’re a student at Michigan Tech or live elsewhere in the UP or eastern Wisconsin, a Ski Cooper pass would pair very well with a $99 Bohemia season pass.

Outside of the UP, however, Indy owns the Midwest, mostly due to its deals with Lutsen, Minnesota and Granite Peak, Wisconsin – two of the region’s largest and best ski areas – and Crystal, Caberfae, and Shanty Creek in Michigan’s Lower Peninsula (Cooper skiers also have Crystal access). Cooper has just five ski areas across Minnesota and Wisconsin, to Indy’s 10.

West

The two passes are most even in the West. They share seven partners, but Indy owns Washington and Ski Cooper unsurprisingly has a substantial footprint in its home state of Colorado. This makes sense: Indy is the only national pass that did not emerge from, is not based in, and has no presence in Colorado. Founded in 2019 by Portland, Oregon-based Doug Fish, the pass launched around strength in Washington and Idaho, and has steadily built out its partners in the Upper Rockies.

But it’s hard to sort out who really has the advantage here. Together, the passes would be almost perfect, with Ski Cooper’s partners filling in Indy’s holes in New Mexico, Colorado, Southern California, and Tahoe; and Indy bringing strength in the Pacific Northwest, Montana, Idaho, and British Columbia. It probably depends on where you live. I doubt Indy is selling many passes in Colorado, and I imagine Ski Cooper is selling most of theirs in-state.

*Indy and Ski Cooper’s shared partners are Eaglecrest, Alaska; Mt. Ashland, Oregon; Brundage and Soldier Mountain, Idaho; Powder Mountain and Eagle Point, Utah; Snow King, Wyoming; Buck Hill, Minnesota; Nordic Mountain and Little Switzerland, Wisconsin; Big Powderhorn, Pine Mountain, and Crystal Mountain, Michigan; Greek Peak, New York; and Black Mountain, New Hampshire.

The decision to give not give away tickets is harder than it sounds

For ski areas deciding on which coalition to join, the choice is more complicated. For years, reciprocal coalitions such as the Freedom Pass and the Powder Alliance were the best idea independent mountains had for joining forces against Vail and Alterra. Ski Cooper agrees to comp three tickets for each Greek Peak passholder, and Greek Peak will comp three tickets for each Ski Cooper passholder. Over the course of a season, this can add up to a significant number of skier visits. Torsell estimates that between six and eight percent of his mountain’s skier visits are comps from partner resorts, and roughly half of those are from Ski Cooper’s Colorado partners: Loveland, Monarch, Sunlight, and Powderhorn.

In 2019, Doug Fish introduced an alternative model. For each skier visit made on an Indy Pass, ski areas would get a cash redemption from Indy, taken from the total pool generated by pass sales (Indy keeps a small percentage of that total). This is the same model Vail and Alterra use to compensate their non-owned partners: each day a skier swipes their Epic Pass at Telluride or their Ikon Pass at Jackson Hole, the ski areas are compensated. The redemption is less than the mountains would have gotten had a skier purchased a walk-up ticket, but few people pay that so-called “rack rate.” By joining the Epic or Ikon or Indy passes, resorts plug into a national marketing network that is almost guaranteed to send them skiers they would not have drawn otherwise.

Almost every ski area in the country is now part of some coalition or another, whether that’s a nationally marketed one like the aforementioned passes, or a bespoke network like Ski Cooper’s. The Northeast, where megapasses are still somewhat novel and ski areas are both densely built and hyper-adapted to the specific needs of local communities, lags somewhat. This is likely to change for all but the Mad River Glens of the world, mountains so singular that there is no replacement for them. As I’ve written before, there aren’t many of those.

Projecting ahead 10 or 15 years, the logical end-state would seem to be a growth in Indy-style passes and a decline in the number of comp ticket deals. But there’s nothing inevitable about that. Ski areas themselves still see value in both – as mentioned above, Ski Cooper and Indy share 15 partners; six of Indy’s partners are also part of the Powder Alliance. Many of Indy’s partners also retain outside reciprocal partnerships: Eaglecrest is a Powder Alliance member, a Ski Cooper partner, and has built its own separate web of partnerships. In a handshake industry like skiing, such deals can be tough to unwind – when Schweitzer joined the Ikon Pass earlier this year, it exited the Powder Alliance, but kept reciprocal partnerships with a host of longtime partners, including Whitewater, Sugar Bowl, Bridger Bowl, and Whitefish.

“There is no right or wrong way to do this and many of our resorts use both Indy Pass and reciprocal agreements,” said Fish. “Every resort’s marketing strategy is different. Location, competitive landscape, capacity restrictions, target yield, and passholder preferences all determine what the best options are for reciprocity and/or third-party passes.”

For now, the reciprocal model seems resilient. “I've had many conversations with Doug Fish and Indy Pass,” Torsell said. “Great guy. We have a great relationship, but our thing is working for us. I'm glad that a lot of areas seem to have bought into the Indy Pass thing, and I think it's probably working well for them. Different models work well for different people.”

Indy’s secret advantage: Shifting the cost to skiers

If reciprocal partnerships eventually dissolve, it will probably be for one very simple reason: not all ski areas are created equal. These sorts of imbalances are exactly what led to the near death of the Freedom Pass in the Northeast.

“We were kind of the big dog on that pass, if you will, and so I think people were buying passes at other places knowing that they’d get three days here,” Bolton Valley President Lindsay DesLauriers told me on The Storm Skiing Podcast earlier this year. “We were giving out a lot of free passes, and I don’t think that anybody was buying a Bolton pass to go ski at the other ski areas. … We were on the giving end of that in a way that wasn’t giving back to us.”

The Freedom Pass reoriented itself under a primarily western roster after Bolton, Magic, Vermont, and Plattekill fled, but the Indy Pass solves this imbalance by paying ski areas for each visit. That means Jay Peak is going to get more redemptions – and more money – than Snow Ridge. Since the yield – or amount each ski area gets for an Indy Pass redemption – is based upon a ski area’s walk-up ticket price, more expensive ski areas such as Waterville Valley will also get more per visit than more affordable ones, such as Suicide Six in Vermont or Black Mountain in New Hampshire.

The Indy Pass delivers another, subtler advantage to partner mountains: it shifts the cost of building and maintaining the partnership network to what is essentially a vendor, and the cost of the partner lift tickets from the ski areas themselves to the skiers. It’s skiing’s version of pick-your-own-apple farms, where people pay you to do something paid laborers would traditionally do. A Ski Cooper passholder doesn’t pay any extra for access to the partner network – it is free and automatic. A Magic Mountain passholder has to actively choose to add on an Indy Pass and pay the additional $189, on top of the $699 pass (early-bird price was $599). Each partner visit those skiers make then generates a check from Indy; each Indy visit to Magic likewise generates a redemption. And Indy, not Magic, manages the partner roster.

“The main difference between the Indy Pass and reciprocal agreements is the revenue component,” said Fish. “If a resort is unable or unwilling to provide free lift tickets to outside passholders then the Indy Pass might make sense.

“We offer a 30% discount to season pass holders at our partner resorts. The Indy AddOn Pass works like a reciprocal but revenue is generated with each visit. Since only a small percentage of season passholders take advantage of reciprocal visits, the AddOn Pass provides a mechanism for resorts to offer reciprocal benefits only to those who want them and are willing to pay a little extra.”

“This is not a national pass,” says the creator of the best non-Epic or -Ikon national season pass in skiing

I’m writing about Ski Cooper’s pass as though it materialized out of the ether last week, but the mountain has been building its partner network for over a decade. As a small mountain in a big-mountain state, it’s been easy to overlook. It deserves a bigger spotlight, even though Torsell insists that he is not trying to create a national ski pass.

“There are a handful of people, if they're in an area that's concentrated with our partners, that might get our pass,” said Torsell. “‘We're just going to buy the Cooper pass. We can ski here and we can go out there.’ But honestly that's not the objective.”

Still, for those in the nether-regions who are interested, Ski Cooper mails out their passes (to avoid “helacious lines for the first two or three weeks of the season,” Torsell says), so there’s nothing stopping a Pennsylvania skier from snatching a Cooper pass, racking up 12 days between Laurel, Hidden Valley, Seven Springs, and Holiday Valley, and then heading west for a week to hit Cooper and its Colorado partners.

Torsell says that Cooper’s pass sales have grown five to eight percent per year for years, even as the Epic Pass expanded its scope and the Mountain Collective and Ikon Passes entered the Colorado market. The mountain recorded record revenue and skier visits last season, according to the Leadville Herald. Whether that is related to the growth in the partner network and bargain pass is unclear, though Torsell noted a surge in pass sales “probably closer to 25 percent” after Cooper dropped the price for renewing passholders to just $199 and new passholders to $249 for the 2020-21 season. That was a Covid concession to acknowledge the difficult economic times and the loss of the tail-end of the 2019-20 season, but Torsell said the momentum has continued into this offseason, with a “record first day” of pass sales earlier this month.

And the partner deals do seem to be driving out-of-state visits. “We had a lot more visits than I thought we would get from the Mid-Atlantic and the East,” Torsell said of the 2020-21 ski season. “I was very pleased. I grew up in Pennsylvania and we had some new partners that we signed on with last year that drove a pretty significant number of visits. Not huge by any means. But for the distance factor there, I don't know if the word just spread or what happened, but that was nice. And we always do a lot of visits from the upper Midwest.”

Ski Cooper’s partner network – like Indy’s – will continue to evolve. This year’s impressive 48-member network is down from 55 last year, even with new partners Mt. Ashland, Lee Canyon, Mt. Baldy, and Soldier Mountain joining in the offseason. Renewal talks are underway with several partners, including Pennsylvania’s Blue Mountain, which Alterra parent KSL recently purchased.

Torsell at first denied that Ski Cooper’s pass was a response to the advent of the Epic and Ikon passes, but his thinking seemed to evolve as we talked. “I guess deep enough in my heart, yeah, it is a little bit of a response to it because it has become such a fad thing,” he said toward the end of our call. “I look at the Epic Pass and the deals that are out there, and it's phenomenal, but it’s like buying an ink-jet printer: you can buy the printer for $39, then once you have it, you gotta pay a lot of money to keep feeding it ink. That's the way I look at like the Epic Pass. Sure you get your pass for whatever it is, $599, $799, $899 [current Epic Pass prices are here], which is wonderful if you're disciplined enough to go there and just ski, and not spend another $3,000 eating.”

However Ski Cooper wants to position this thing, I’m calling it a national budget megapass. And a pretty good one. Get on this one while you can – prices go up Aug. 1.

I wondered how long it would take for Cooper’s massive reciprocity agreements to be noticed — Monarch also does a tremendous job, especially for resorts in Colorado (has 3-day agreements with both Copper(!) and A-Basin(!) It’s cheaper to get a Monarch season pass than two three-packs separately at each). Getting either Cooper or Monarch in addition to a Epic is one of the best “secrets” around, as neither mountain gets lift lines (even on holidays so best mountains to go to during them), and you also can ski the majority of the mountains in CO.

Wow this is a deal. Last year I went 3 powder days to holiday valley and each ticket was around $85. This years window rate is 93, 3 lift tickets to holiday valley itself pays for this + 1 day anywhere else and you’re on top.