Who

Chris Cushing, Principal of Mountain Planning at SE Group

Recorded on

April 3, 2025

About SE Group

From the company’s website:

WE ARE

Mountain planners, landscape architects, environmental analysts, and community and recreation planners. From master planning to conceptual design and permitting, we are your trusted partner in creating exceptional experiences and places.

WE BELIEVE

That human and ecological wellbeing forms the foundation for thriving communities.

WE EXIST

To enrich people’s lives through the power of outdoor recreation.

If that doesn’t mean anything to you, then this will:

Why I interviewed him

Nature versus nurture: God throws together the recipe, we bake the casserole. A way to explain humans. Sure he’s six foot nine, but his mom dropped him into the intensive knitting program at Montessori school 232, so he can’t play basketball for shit. Or identical twins, separated at birth. One grows up as Sir Rutherford Ignacious Beaumont XIV and invents time travel. The other grows up as Buford and is the number seven at Okey-Doke’s Quick Oil Change & Cannabis Emporium. The guts matter a lot, but so does the food.

This is true of ski areas as well. An earthquake here, a glacier there, maybe a volcanic eruption, and, presto: a non-flat part of the earth on which we may potentially ski. The rest is up to us.

It helps if nature was thoughtful enough to add slopes of varying but consistent pitch, a suitable rise from top to bottom, a consistent supply of snow, a flat area at the base, and some sort of natural conduit through which to move people and vehicles. But none of that is strictly necessary. Us humans (nurture), can punch green trails across solid-black fall lines (Jackson Hole), bulldoze a bigger hill (Caberfae), create snow where the clouds decline to (Wintergreen, 2022-23), plant the resort base at the summit (Blue Knob), or send skiers by boat (Eaglecrest).

Someone makes all that happen. In North America, that someone is often SE Group, or their competitor, Ecosign. SE Group helps ski areas evolve into even better ski areas. That means helping to plan terrain expansions, lift replacements, snowmaking upgrades, transit connections, parking enhancements, and whatever built environment is under the ski area’s control. SE Group is often the machine behind those Forest Service ski area master development plans that I so often spotlight. For example, Vail Mountain:

When I talk about Alta consolidating seven slow lifts into four fast lifts; or Little Switzerland carving their mini-kingdom into beginner, parkbrah, and racer domains; or Mount Bachelor boosting its power supply to run more efficiently, this is the sort of thing that SE plots out (I’m not certain if they were involved in any or all of those projects).

Analyzing this deliberate crafting of a natural bump into a human playground is the core of what The Storm is. I love, skiing, sure, but specifically lift-served skiing. I’m sure it’s great to commune with the raccoons or whatever it is you people do when you discuss “skinning” and “AT setups.” But nature left a few things out. Such as: ski patrol, evacuation sleds, avalanche control, toilet paper, water fountains, firepits, and a place to charge my phone. Oh and chairlifts. And directional signs with trail ratings. And a snack bar.

Skiing is torn between competing and contradictory narratives: the misanthropic, which hates crowds and most skiers not deemed sufficiently hardcore; the naturalistic, which mistakes ski resorts with the bucolic experience that is only possible in the backcountry; the preservationist, with its museum-ish aspirations to glasswall the obsolete; the hyperactive, insisting on all fast lifts and groomed runs; the fatalists, who assume inevitable death-of-concept in a warming world.

None of these quite gets it. Ski areas are centers of joy and memory and bonhomie and possibility. But they are also (mostly), businesses. They are also parks, designed to appeal to as many skiers as possible. They are centers of organized risk, softened to minimize catastrophic outcomes. They must enlist machine aid to complement natural snowfall and move skiers up those meddlesome but necessary hills. Ski areas are nature, softened and smoothed and labelled by their civilized stewards, until the land is not exactly a representation of either man or God, but a strange and wonderful hybrid of both.

What we talked about

Old-school Cottonwoods vibe; “the Ikon Pass has just changed the industry so dramatically”; how to become a mountain planner for a living; what the mountain-planning vocation looked like in the mid-1980s; the detachable lift arrives; how to consolidate lifts without sacrificing skier experience; when is a lift not OK?; a surface lift resurgence?; how sanctioned glades changed ski areas; the evolution of terrain parks away from mega-features; the importance of terrain parks to small ski areas; reworking trails to reduce skier collisions; the curse of the traverse; making Jackson more approachable; on terrain balance; how megapasses are redistributing skier visits; how to expand a ski area without making traffic worse; ski areas that could evolve into major destinations; and ski area as public park or piece of art.

What I got wrong

I blanked on the name of the famous double chair at A-Basin. It is Pallavicini.

I called Crystal Mountain’s two-seater served terrain “North Country or whatever” – it is actually called “Northway.”

I said that Deer Valley would become the fourth- or fifth-largest ski resort in the nation once its expansion was finished. It will become the sixth-largest, at 4,926 acres, when the next expansion phase opens for winter 2025-26, and will become the fourth-largest, at 5,726 acres, at full build out.

I estimated Kendall Mountain’s current lift-served ski footprint at 200 vertical feet; it is 240 feet.

Why now was a good time for this interview

We have a tendency, particularly in outdoor circles, to lionize the natural and shame the human. Development policy in the United States leans heavily toward “don’t,” even in areas already designated for intensive recreation. We mustn’t, plea activists: expand the Palisades Tahoe base village; build a gondola up Little Cottonwood Canyon; expand ski terrain contiguous with already-existing ski terrain at Grand Targhee.

I understand these impulses, but I believe they are misguided. Intensive but thoughtful, human-scaled development directly within and adjacent to already-disturbed lands is the best way to limit the larger-scale, long-term manmade footprint that chews up vast natural tracts. That is: build 1,000 beds in what is now a bleak parking lot at Palisades Tahoe, and you limit the need for homes to be carved out of surrounding forests, and for hundreds of cars to daytrip into the ski area. Done right, you even create a walkable community of the sort that America conspicuously lacks.

To push back against, and gradually change, the Culture of No fueling America’s mountain town livability crises, we need exhibits of these sorts of projects actually working. More Whistlers (built from scratch in the 1980s to balance tourism and community) and fewer Aspens (grandfathered into ski town status with a classic street and building grid, but compromised by profiteers before we knew any better). This is the sort of work SE is doing: how do we build a better interface between civilization and nature, so that the former complements, rather than spoils, the latter?

All of which is a little tangential to this particular podcast conversation, which focuses mostly on the ski areas themselves. But America’s ski centers, established largely in the middle of the last century, are aging with the towns around them. Just about everything, from lifts to lodges to roads to pipes, has reached replacement age. Replacement is a burden, but also an opportunity to create a better version of something. Our ski areas will not only have faster lifts and newer snowguns – they will have fewer lifts and fewer guns that carry more people and make more snow, just as our built footprint, thoughtfully designed, can provide more homes for more people on less space and deliver more skiers with fewer vehicles.

In a way, this podcast is almost a canonical Storm conversation. It should, perhaps, have been episode one, as every conversation since has dealt with some version of this question: how do humans sculpt a little piece of nature into a snowy park that we visit for fun? That is not an easy or obvious question to answer, which is why SE Group exists. Much as I admire our rough-and-tumble Dave McCoy-type founders, that improvisational style is trickier to execute in our highly regulated, activist present.

And so we rely on artist-architects of the SE sort, who inject the natural with the human without draining what is essential from either. Done well, this crafted experience feels wild. Done poorly – as so much of our legacy built environment has been – and you generate resistance to future development, even if that future development is better. But no one falls in love with a blueprint. Experiencing a ski area as whatever it is you think a ski area should be is something you have to feel. And though there is a sort of magic animating places like Alta and Taos and Mammoth and Mad River Glen and Mount Bohemia, some ineffable thing that bleeds from the earth, these ski areas are also outcomes of a human-driven process, a determination to craft the best version of skiing that could exist for mass human consumption on that shred of the planet.

Podcast Notes

On Mittersill

Mittersill, now part of Cannon Mountain, was once a separate ski area. It petered out in the mid-‘80s, then became a sort of Cannon backcountry zone circa 2009. The Mittersill double arrived in 2010, followed by a T-bar in 2016.

On chairlift consolidation

I mention several ski areas that replaced a bunch of lifts with fewer lifts:

The Highlands

In 2023, Boyne-owned The Highlands wiped out three ancient Riblet triples and replaced them with this glorious bubble six-pack:

Here’s a before-and-after:

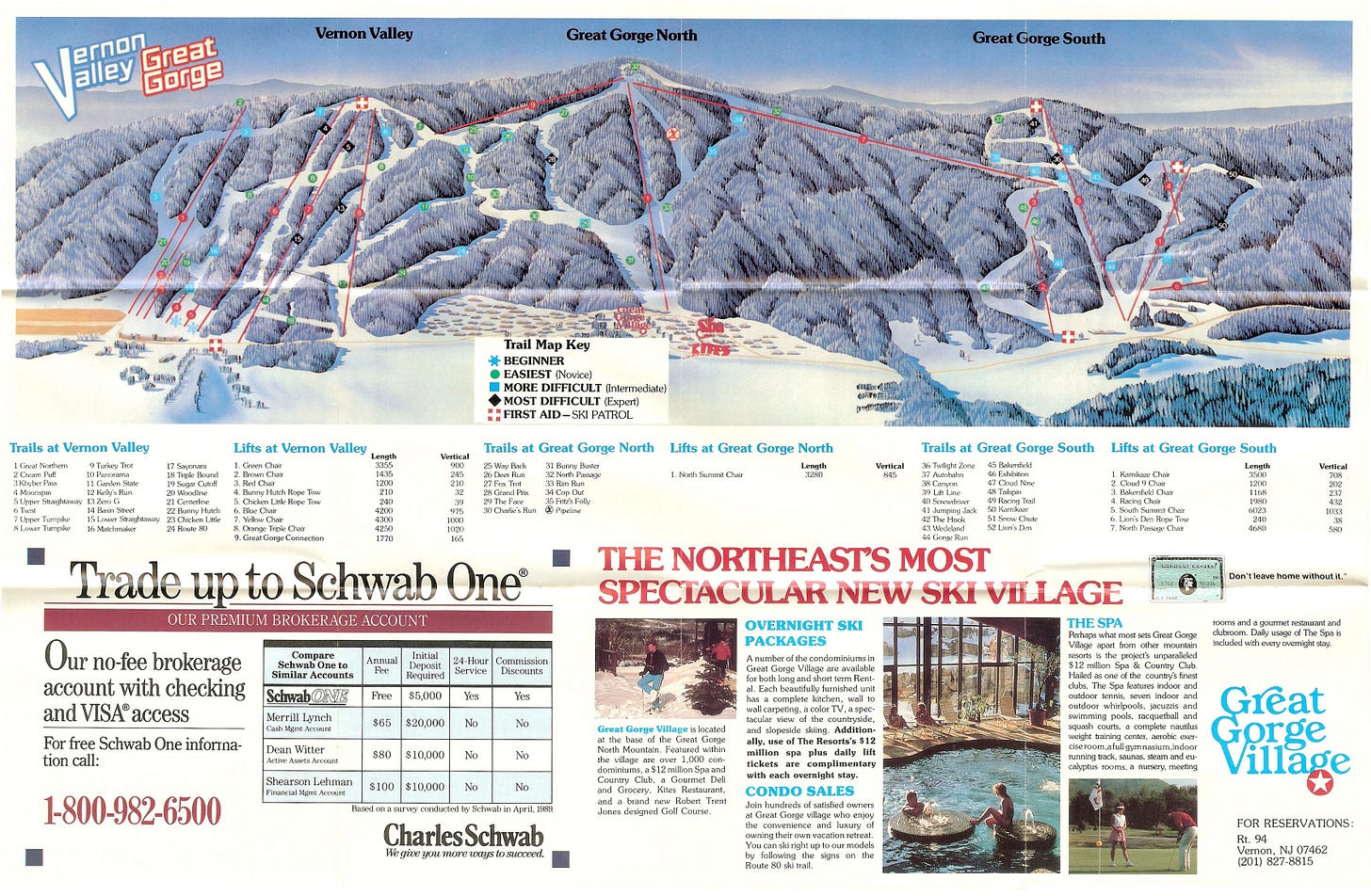

Vernon Valley-Great Gorge/Mountain Creek

I’ve called Intrawest’s transformation of Vernon Valley-Great Gorge into Mountain Creek “perhaps the largest single-season overhaul of a ski area in the history of lift-served skiing.” Maybe someone can prove me wrong, but just look at this place circa 1989:

It looked substantively the same in 1998, when, in a single summer, Intrawest tore out 18 lifts – 15 double chairs, two platters, and a T-bar, plus God knows how many ropetows – and replaced them with two high-speed quads, two fixed-grip quads, and a bucket-style Cabriolet lift that every normal ski area uses as a parking lot transit machine:

I discussed this incredible transformation with current Hermitage Club GM Bill Benneyan, who worked at Mountain Creek in 1998, back in 2020:

I misspoke on the podcast, saying that Intrawest had pulled out “something like a dozen lifts” and replaced them with “three or four” in 1998.

Kimberley

Back in the time before social media, Kimberley, British Columbia ran four frontside chairlifts: a high-speed quad, a triple, a double, and a T-bar:

Beginning in 2001, the ski area slowly removed everything except the quad. Which was fine until an arsonist set fire to Kimberley’s North Star Express in 2021, meaning skiers had no lift-served option to the backside terrain:

I discussed this whole strange sequence of events with Andy Cohen, longtime GM of sister resort Fernie, on the podcast last year:

On Revelstoke’s original masterplan

It is astonishing that Revelstoke serves 3,121 acres with just five lifts: a gondola, two high-speed quads, a fixed quad, and a carpet. Most Midwest ski areas spin three times more lifts for three percent of the terrain.

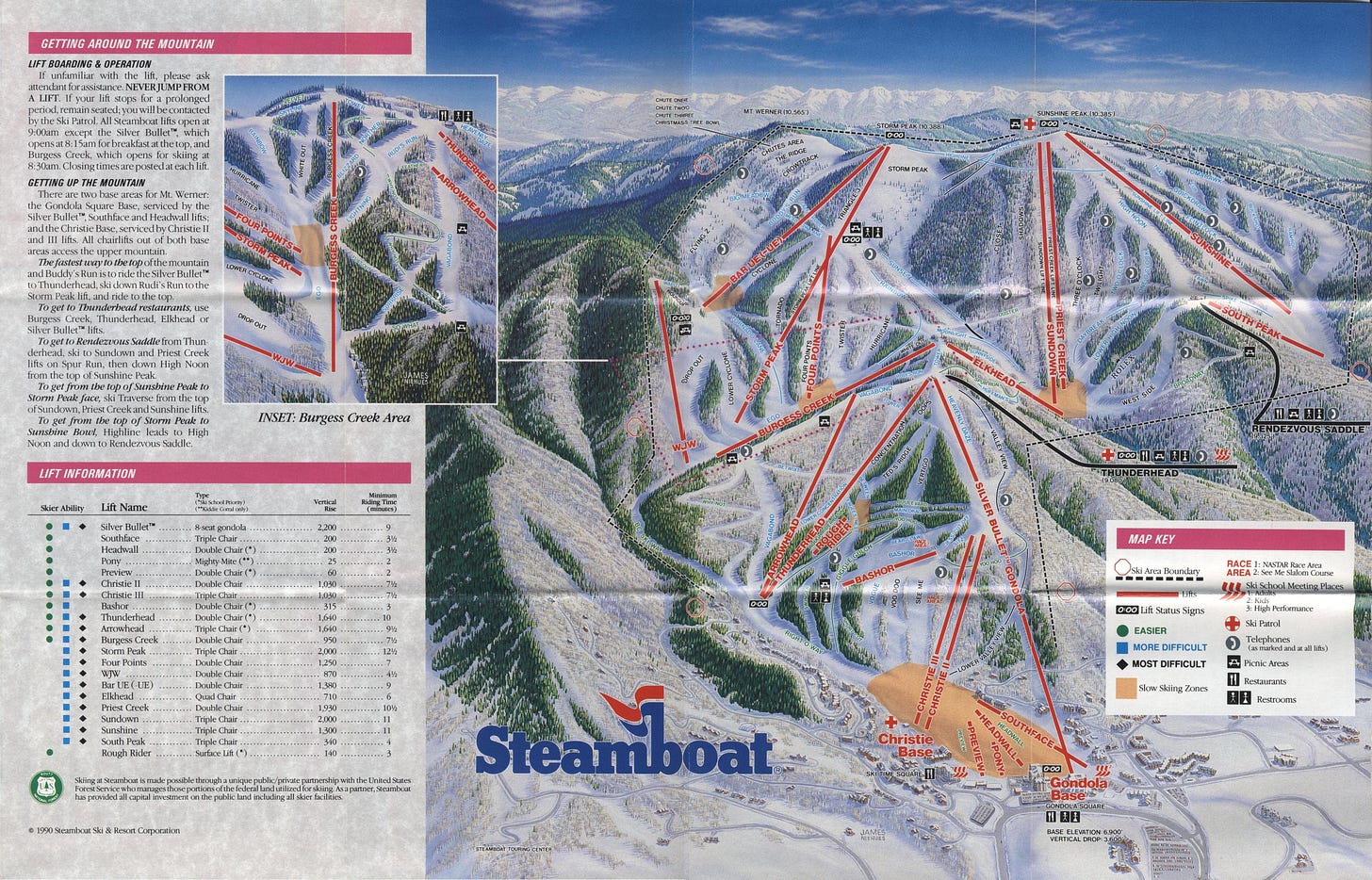

On Priest Creek and Sundown at Steamboat

Steamboat, like many ski areas, once ran two parallel fixed-grip lifts on substantively the same line, with the Priest Creek double and the Sundown triple. The Sundown Express quad arrived in 1992, but Steamboat left Priest Creek standing for occasional overflow until 2021. Here’s Steamboat circa 1990:

Priest Creek is gone, but that entire 1990 lift footprint is nearly unrecognizable. Huge as Steamboat is, every arriving skier squeezes in through a single portal. One of Alterra’s first priorities was to completely re-imagine the base area: sliding the existing gondola looker’s right; installing an additional 10-person, two-stage gondola right beside it; and moving the carpets and learning center to mid-mountain:

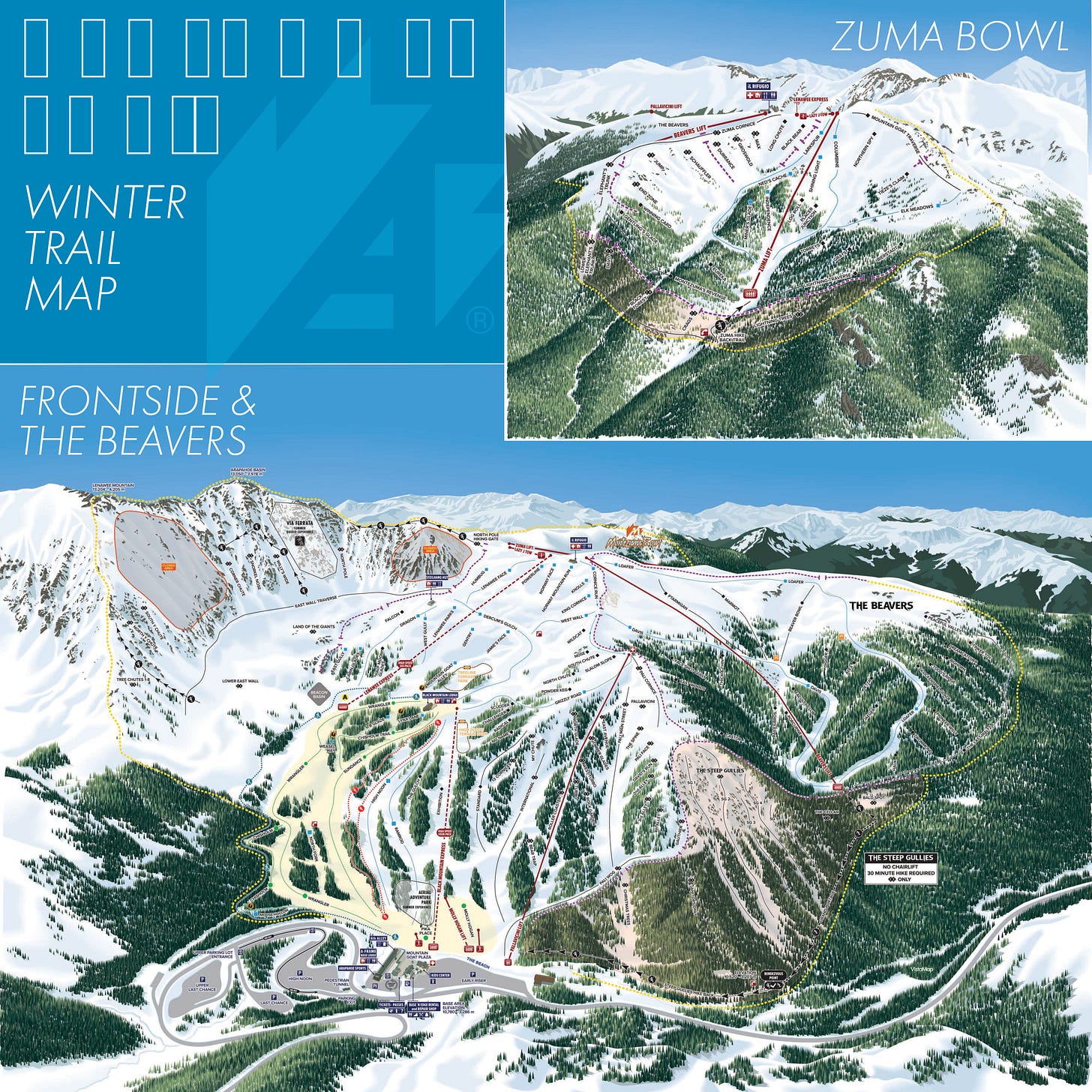

On upgrades at A-Basin

We discuss several upgrades at A-Basin, including Lenawee, Beavers, and Pallavicini. Here’s the trailmap for context:

On moguls on Kachina Peak at Taos

Yeah I’d say this lift draws some traffic:

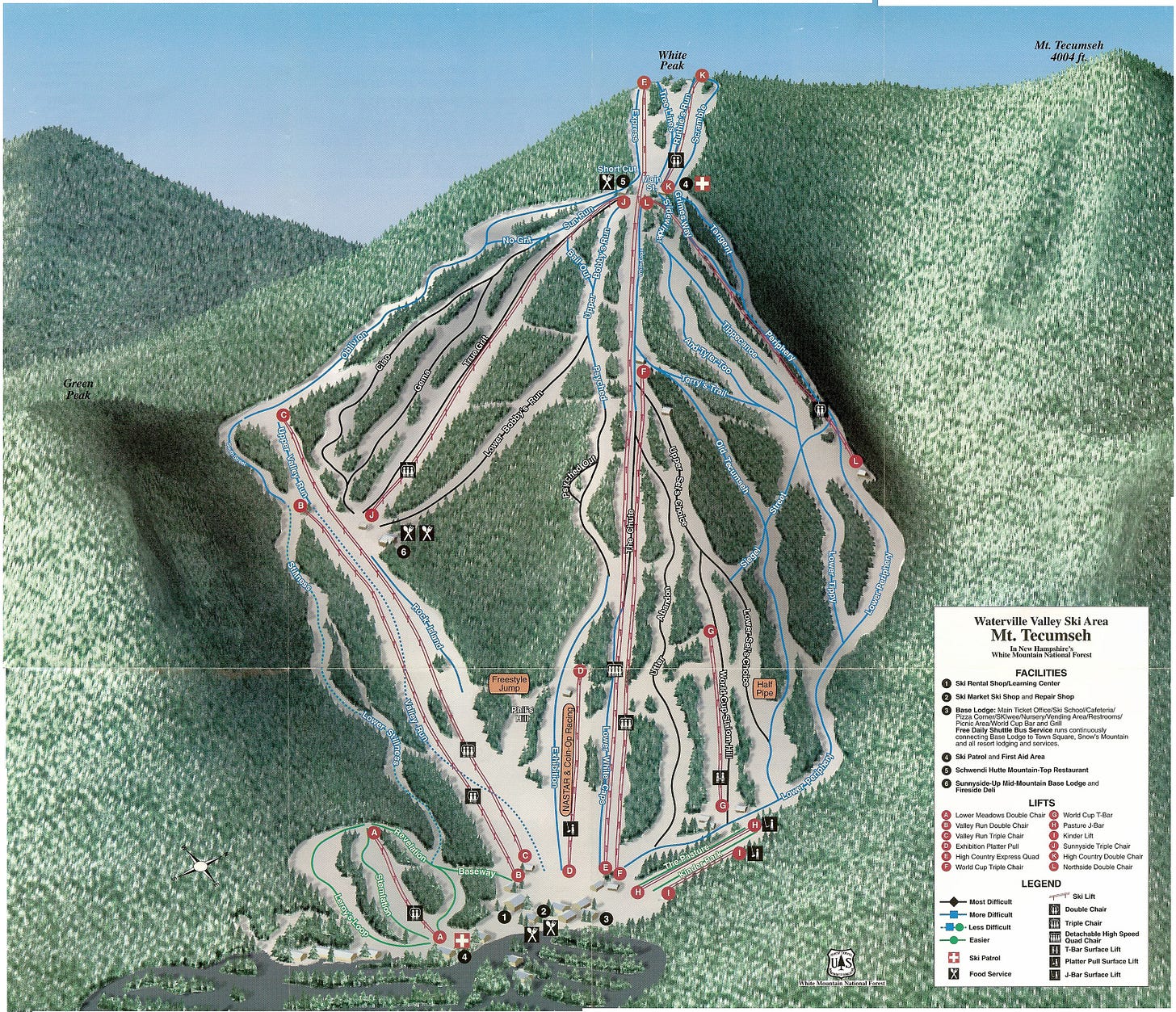

On the T-bar at Waterville Valley

Waterville Valley opened in 1966. Fifty-two years later, mountain officials finally acknowledged that chairlifts do not work on the mountain’s top 400 vertical feet. All it took was a forced 1,585-foot shortening of the resort’s base-to-summit high-speed quad just eight years after its 1988 installation and the legacy double chair’s continued challenges in wind to say, “yeah maybe we’ll just spend 90 percent less to install a lift that’s actually appropriate for this terrain.” That was the High Country T-bar, which arrived in 2018. It is insane to look at ‘90s maps of Waterville pre- and post-chop job:

On Hyland Hills, Minnesota

What an insanely amazing place this is:

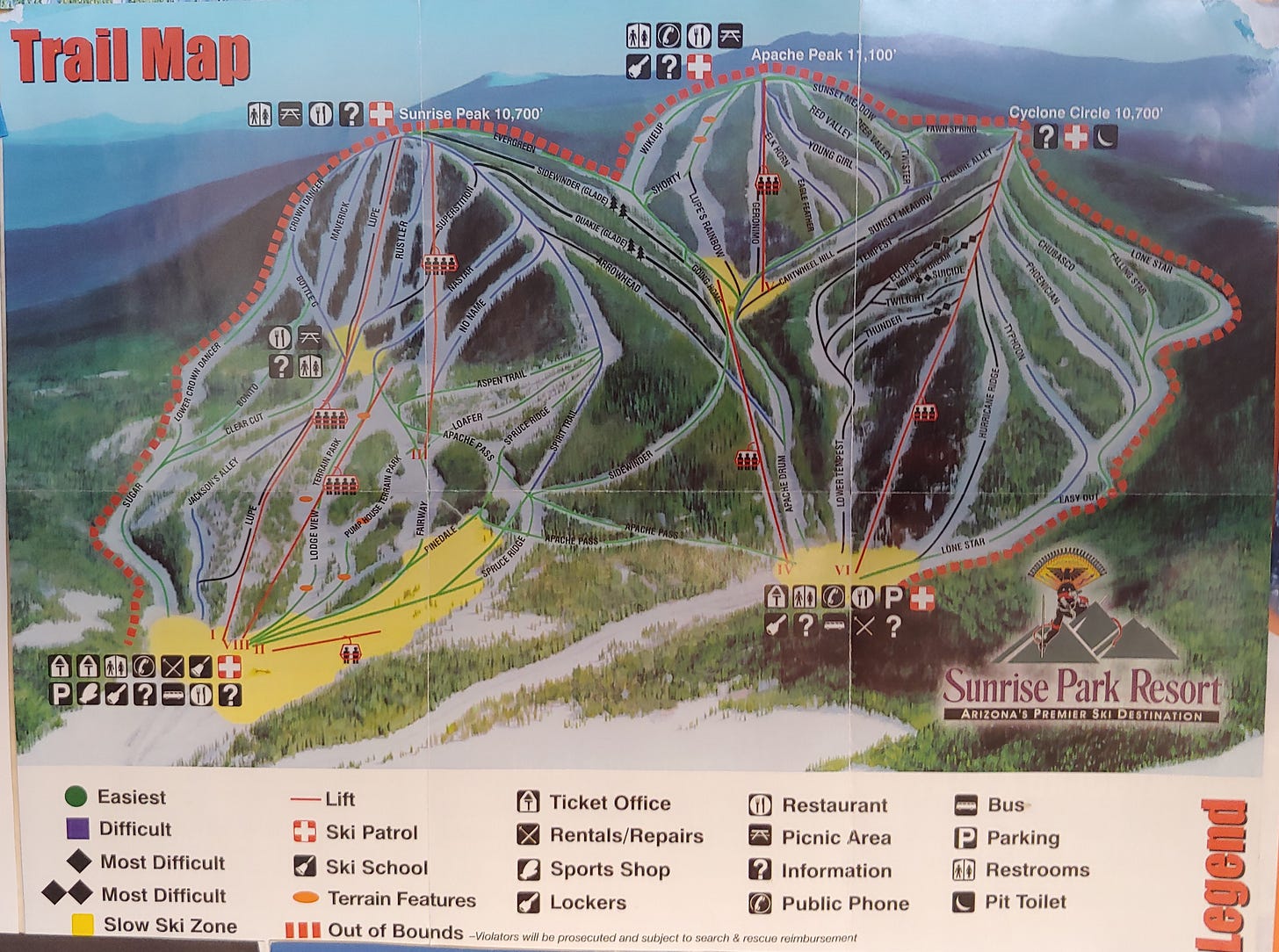

On Sunrise Park

From 1983 to 2017, Sunrise Park, Arizona was home to the most amazing triple chair, a 7,982-foot-long Yan with 352 carriers. Cyclone, as it was known, fell apart at some point and the resort neglected to fix or replace it. A couple of years ago, they re-opened the terrain to lift-served skiing with a low-cost alternative: stringing a ropetow from a green run off the Geronimo lift to where Cyclone used to land.

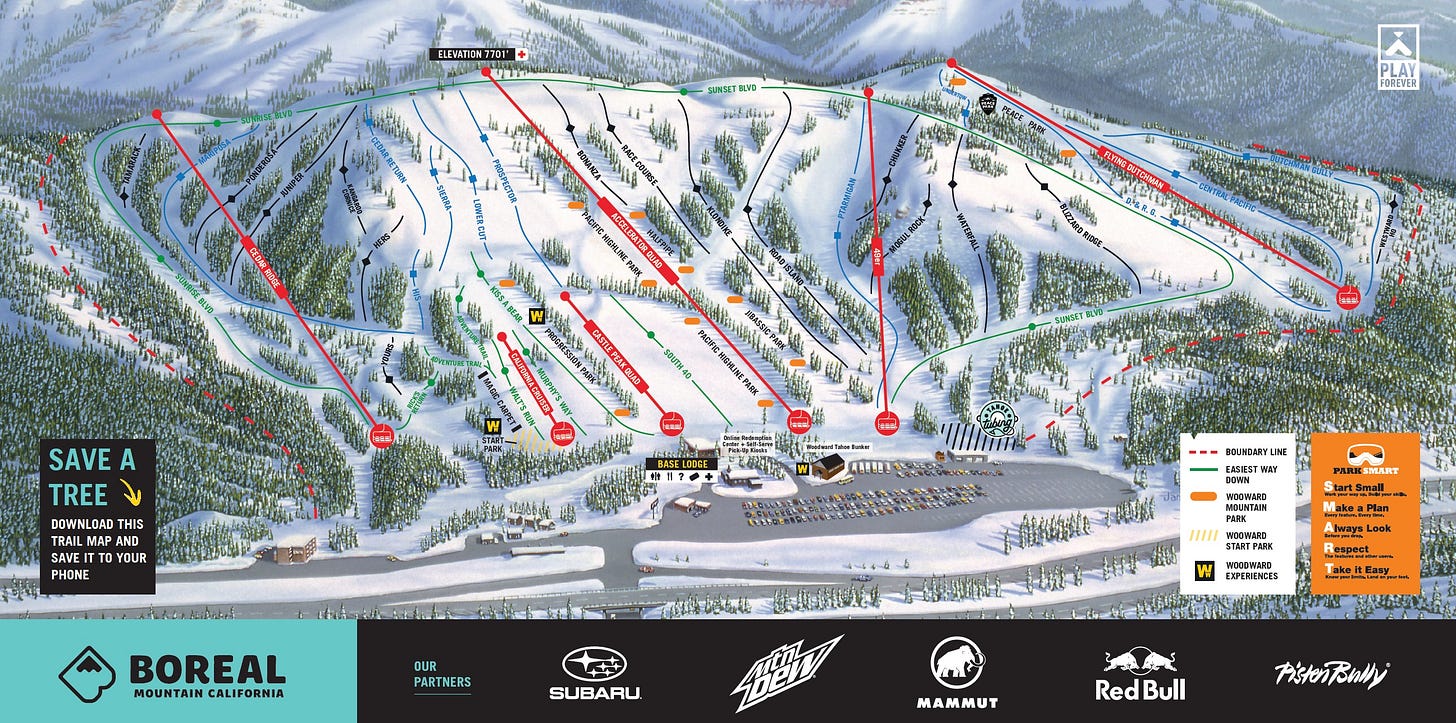

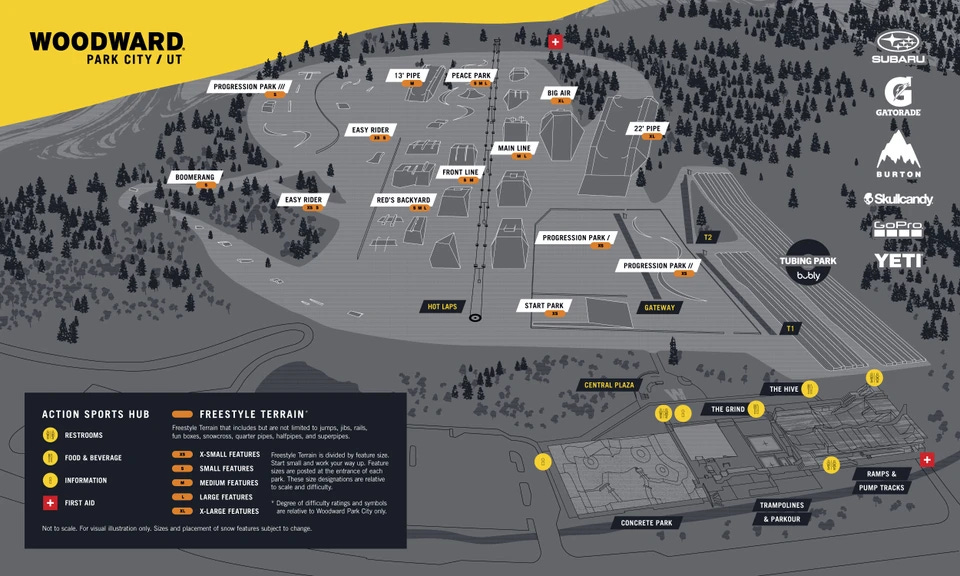

On Woodward Park City and Boreal

Powdr has really differentiated itself with its Woodward terrain parks, which exist at amazing scale at Copper and Bachelor. The company has essentially turned two of its smaller ski areas – Boreal and Woodward Park City – entirely over to terrain parks.

On Killington’s tunnels

You have to zoom in, but you can see them on the looker’s right side of the trailmap: Bunny Buster at Great Northern, Great Bear at Great Northern, and Chute at Great Northern.

On Jackson Hole traverses

Jackson is steep. Engineers hacked it so kids like mine could ride there:

On expansions at Beaver Creek, Keystone, Aspen

Recent Colorado expansions have tended to create vast zones tailored to certain levels of skiers:

Beaver Creek’s McCoy Park is an incredible top-of-the-mountain green zone:

Keystone’s Bergman Bowl planted a high-speed six-pack to serve 550 acres of high-altitude intermediate terrain:

And Aspen – already one of the most challenging mountains in the country – added Hero’s – a fierce black-diamond zone off the summit:

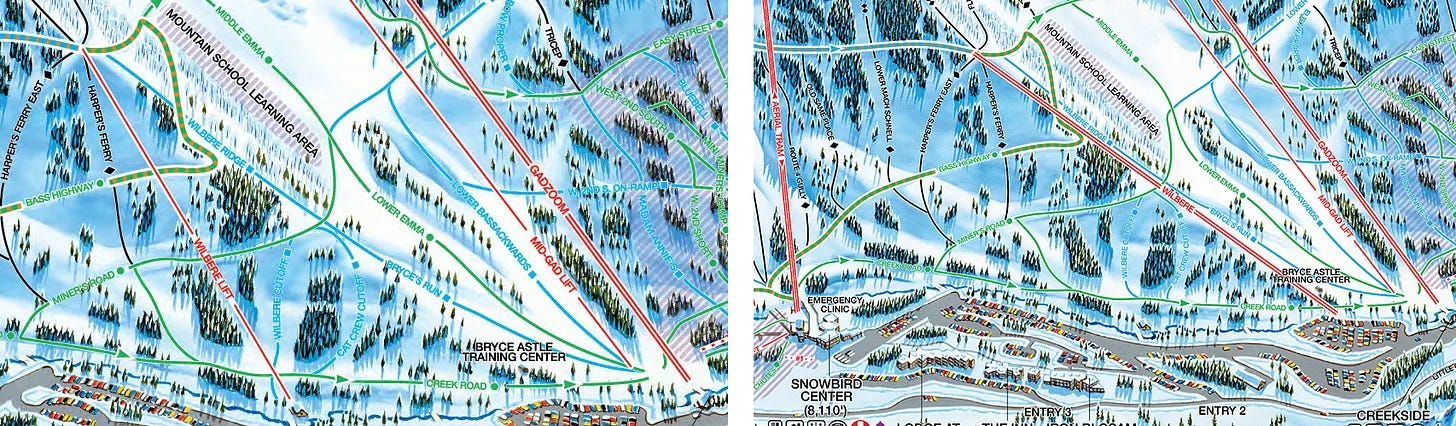

On Wilbere at Snowbird

Wilbere is an example of a chairlift that kept the same name, even as Snowbird upgraded it from a double to a quad and significantly moved the load station and line:

On ski terrain growth in America

Yes, a bunch of ski areas have disappeared since the 1980s, but the raw amount of ski terrain has been increasing steadily over the decades:

On White Pine, Wyoming

Cushing referred to White Pine as a “dinky little ski area” with lots of potential. Here’s a look at the thousand-footer, which billionaire Joe Ricketts purchased last year:

On Deer Valley’s expansion

Yeah, Deer Valley is blowing up:

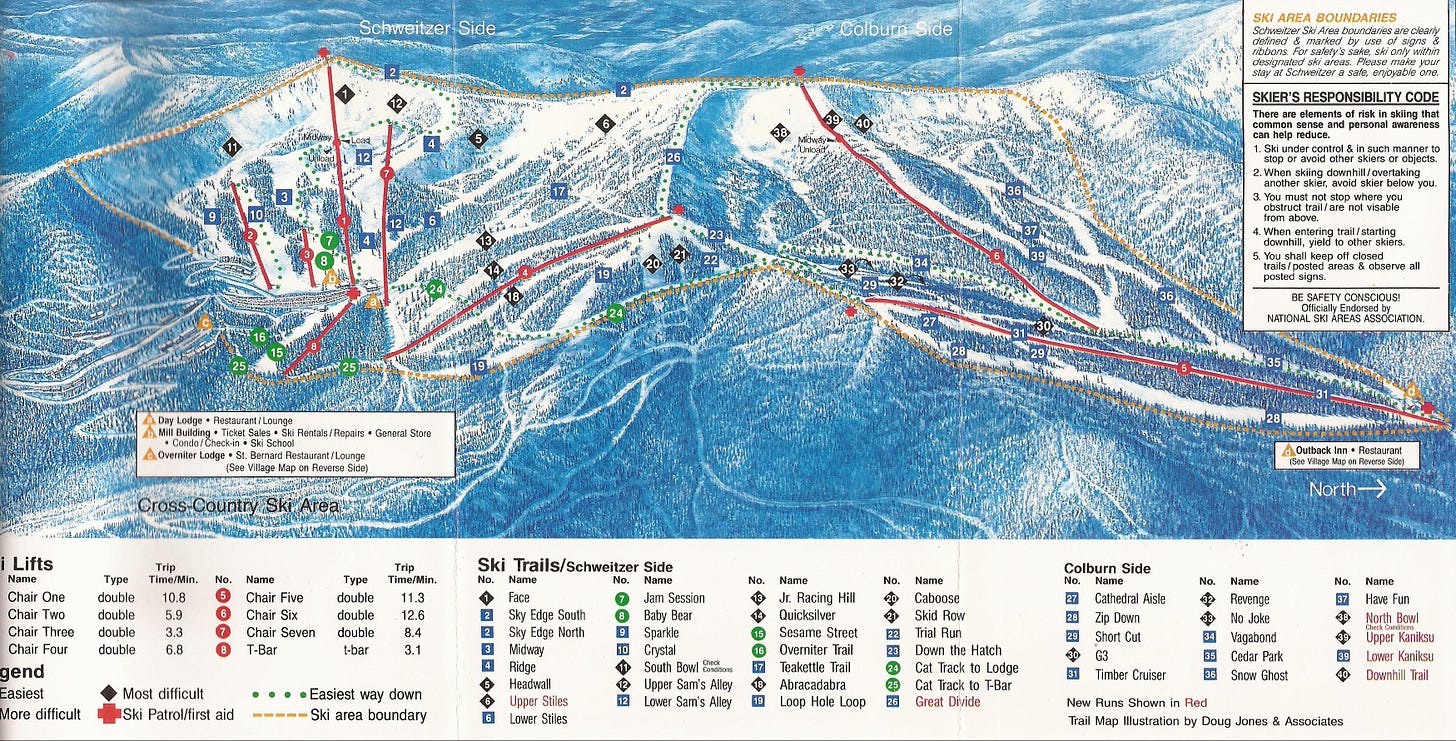

On Schweitzer’s growth

Schweitzer’s transformation has been dramatic: in 1988, the Idaho panhandle resort occupied a large footprint that was served mostly by double chairs:

Today: a modern ski area, with four detach quads, a sixer, and two newer triples – only one old chairlift remains:

On BC transformations

A number of British Columbia ski areas have transformed from nubbins to majors over the past 30 years:

Sun Peaks, then known as Tod Mountain, in 1993

Sun Peaks today:

Fernie in 1996, pre-upward expansion:

Fernie today:

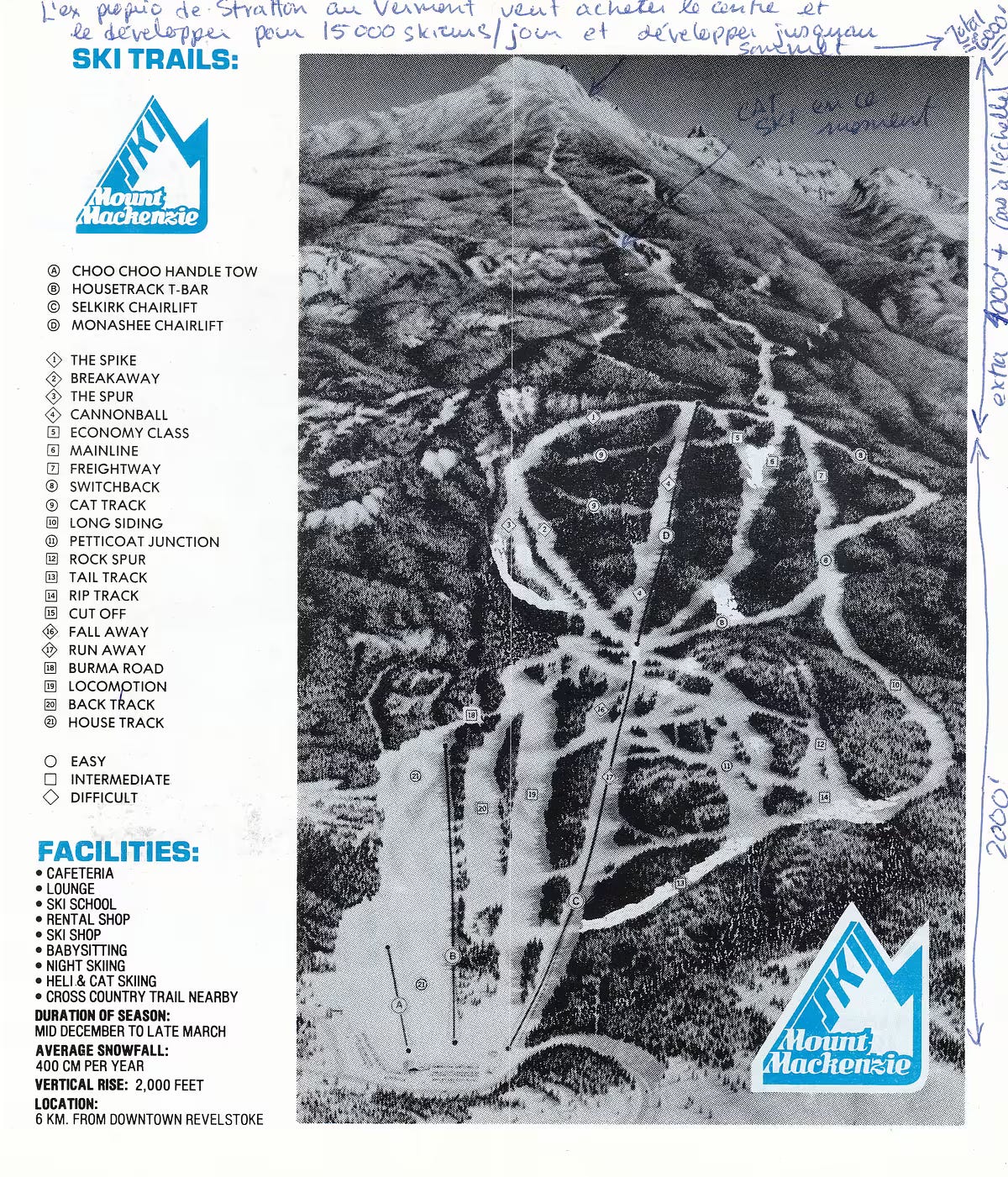

Revelstoke, then known as Mount Mackenzie, in 1996:

Modern Revy:

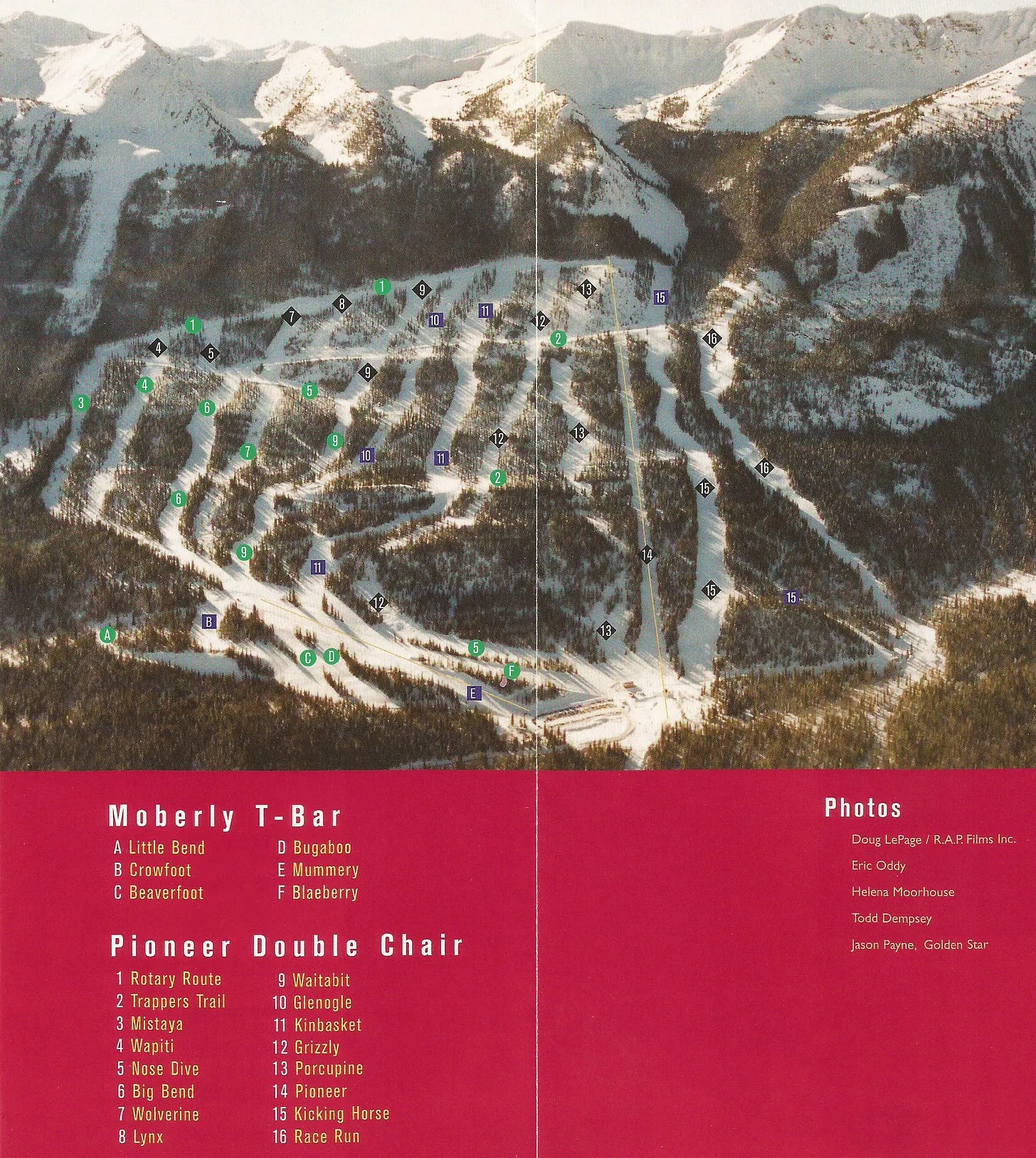

Kicking Horse, then known as “Whitetooth” in 1994:

Kicking Horse today:

On Tamarack’s expansion potential

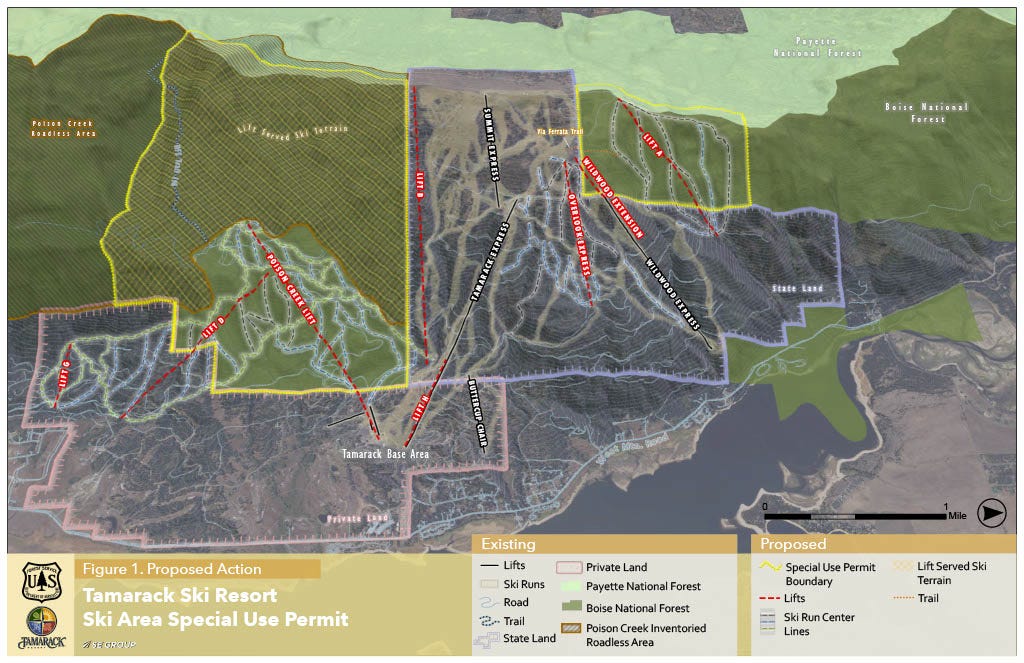

Tamarack sits mostly on Idaho state land, and would like to expand onto adjacent U.S. Forest Service land. Resort President Scott Turlington discussed these plans in depth with me on the pod a few years back:

The mountain’s plans have changed since, with a smaller lift footprint:

On Central Park as a manmade place

New York City’s fabulous Central Park is another chunk of earth that may strike a visitor as natural, but is in fact a manmade work of art crafted from the wilderness. Per the Central Park Conservancy, which, via a public-private partnership with the city, provides the majority of funds, labor, and logistical support to maintain the sprawling complex:

A popular misconception about Central Park is that its 843 acres are the last remaining natural land in Manhattan. While it is a green sanctuary inside a dense, hectic metropolis, this urban park is entirely human-made. It may look like it's naturally occurring, but the flora, landforms, water, and other features of Central Park have not always existed.

Every acre of the Park was meticulously designed and built as part of a larger composition—one that its designers conceived as a "single work of art." Together, they created the Park through the practice that would come to be known as "landscape architecture."