Who

Gary Milliken, Founder of Vista Map

Recorded on

June 13, 2024

About Vista Map

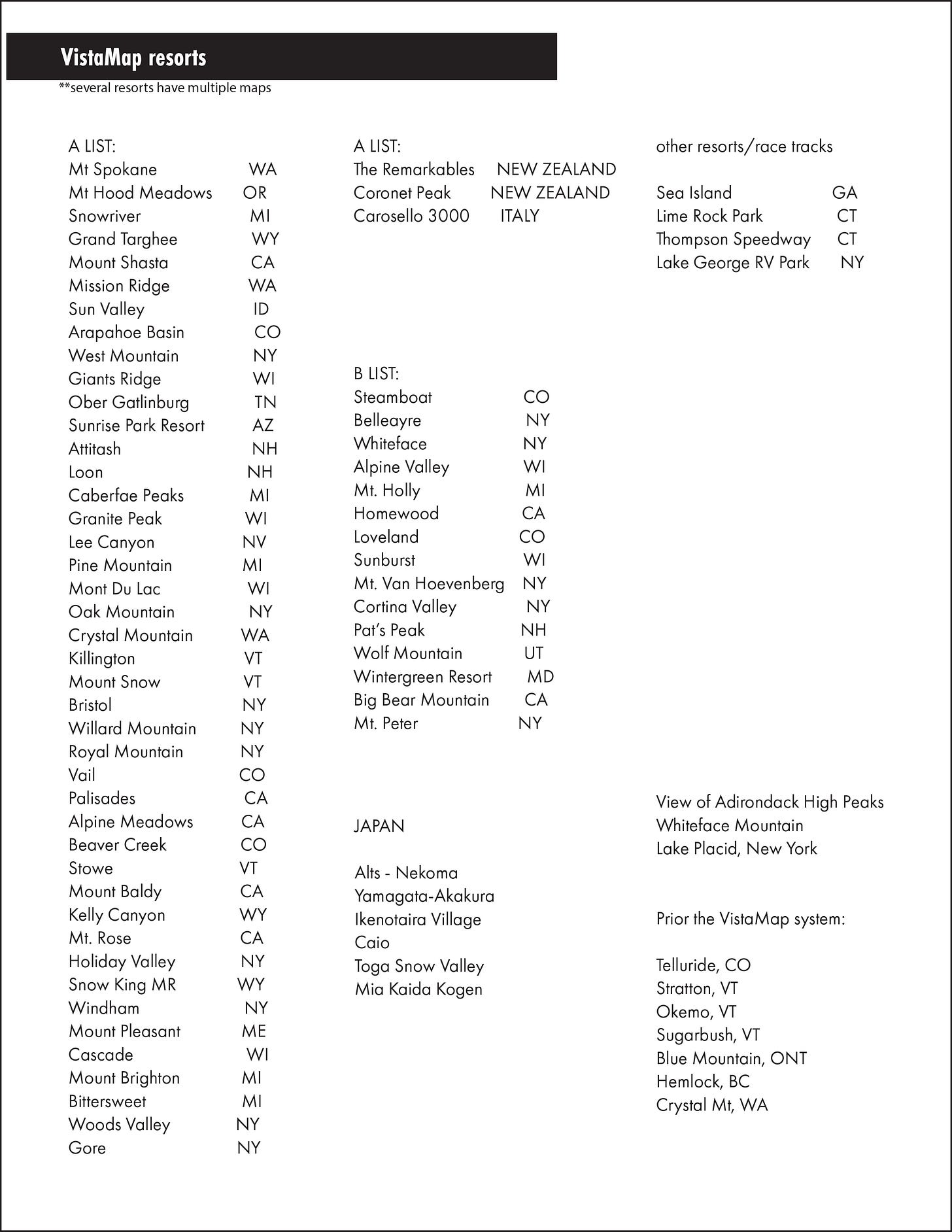

No matter which region of the country you ski in, you’ve probably seen one of Milliken’s maps (A list captures current clients; B list is past clients):

Here’s a little overview video:

Why I interviewed him

The robots are coming. Or so I hear. They will wash our windows and they will build our cars and they will write our novels. They will do all of our mundane things and then they will do all of our special things. And once they can do all of the things that we can do, they will pack us into shipping containers and launch us into space. And we will look back at earth and say dang it we done fucked up.

That future is either five minutes or 500 years away, depending upon whom you ask. But it’s coming and there’s nothing we can do to stop it. OK. But am I the only one still living in a 2024 in which it takes the assistance of at least three humans to complete a purchase at a CVS self-checkout? The little Google hub talky-thingys scattered around our apartment are often stumped by such seering questions as “Hey Google, what’s the weather today?” I believe 19th century wrenchers invented the internal combustion engine and sent it into mass production faster than I can synch our wireless Nintendo Switch controllers with the console. If the robots ever come for me, I’m going to ask them to list the last five presidents of Ohio and watch them short-circuit in a shower of sparks and blown-off sprockets.

We overestimate machines and underestimate humans. No, our brains can’t multiply a sequence of 900-digit numbers in one millisecond or memorize every social security number in America or individually coordinate an army of 10,000 alien assassins to battle a videogame hero. But over a few billion years, we’ve evolved some attributes that are harder to digitally mimic than Bro.AI seems to appreciate. Consider the ridiculous combination of balance, muscle memory, strength, coordination, spatial awareness, and flexibility that it takes to, like, unpack a bag of groceries. If you’ve ever torn an ACL or a rotator cuff, you can appreciate how strong and capable the human body is when it functions normally. Now multiply all of those factors exponentially as you consider how they fuse so that we can navigate a bicycle through a busy city street or build a house or play basketball. Or, for our purposes, load and unload a chairlift, ski down a mogul field, or stomp a FlipDoodle 470 off of the Raging Rhinoceros run at Mt. Sickness.

To which you might say, “who cares? Robots don’t ski. They don’t need to and they never will. And once we install the First Robot Congress, all of us will be free to ski all of the time.” But let’s bring this back to something very simple that it seems as though the robots could do tomorrow, but that they may not be able to do ever: create a ski area trailmap.

This may sound absurd. After all, mountains don’t move around a lot. It’s easy enough to scan one and replicate it in the digital sphere. Everything is then arranged just exactly as it is in reality. With such facsimiles already possible, ski area operators can send these trailmap artists directly into the recycling bin, right?

Probably not anytime soon. And that’s because what robots don’t understand about trailmaps is how humans process mountains. In a ski area trailmap, we don’t need something that exactly recreates the mountain. Rather, we need a guide that converts a landscape that’s hilly and windy and multi-faced and complicated into something as neat and ordered as stocked aisles in a grocery store. We need a three-dimensional environment to make sense in a two-dimensional rendering. And we need it all to work together at a scale shrunken down hundreds of times and stowed in our pocket. Then we need that scale further distorted to make very big things such as ravines and intermountain traverses to look small and to make very small things like complex, multi-trailed beginner areas look big. We need someone to pull the mountain into pieces that work together how we think they work together, understanding that fidelity to our senses matters more than precisely mirroring reality.

But robots don’t get this because robots don’t ski. What data, inherent to the human condition, do we upload to these machines to help them understand how we process the high-speed descent of a snow-covered mountain and how to translate that to a piece of paper? How do we make them understand that this east-facing mountain must appear to face north so that skiers understand how to navigate to and from the adjacent peak, rather than worrying about how tectonic plates arranged the monoliths 60 million years ago? How do the robots know that this lift spanning a two-mile valley between separate ski centers must be represented abstractly, rather than at scale, lest it shrinks the ski trails to incomprehensible minuteness?

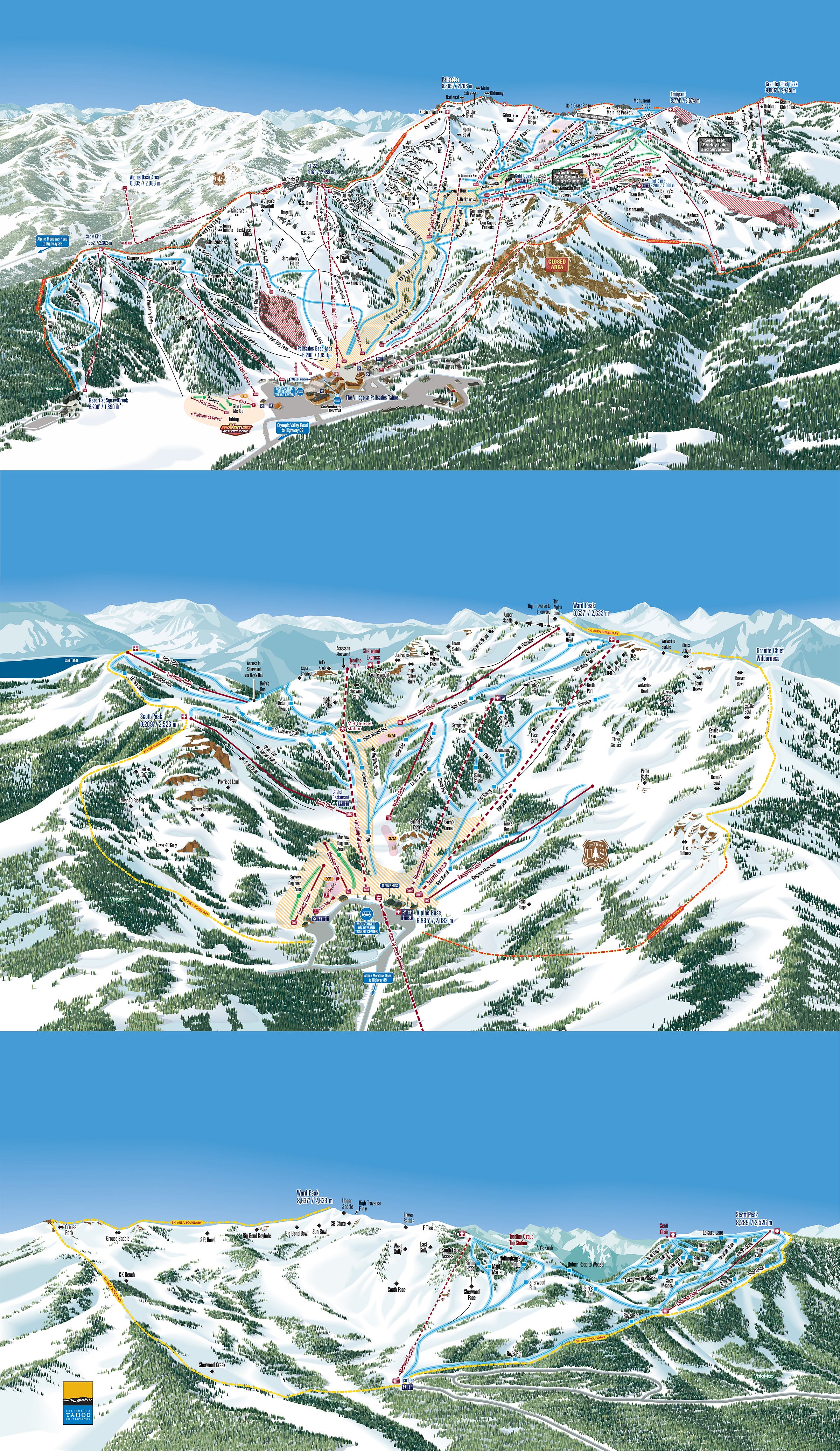

It’s worth noting that Milliken has been a leader in digitizing ski trailmaps, and that this grounding in the digital is the entire basis of his business model, which flexes to the seasonal and year-to-year realities of ever-changing ski areas far more fluidly than laboriously hand-painted maps. But Milliken’s trailmaps are not simply topographic maps painted cartoon colors. They are, rather, cartography-inspired art, reality translated to the abstract without losing its anchors in the physical. In recreating sprawling, multi-faced ski centers such as Palisades Tahoe or Vail Mountain, Milliken, a skier and a human who exists in a complex and nuanced world, is applying the strange blend of talents gifted him by eons of natural selection to do something that no robot will be able to replicate anytime soon.

What we talked about

How late is too late in the year to ask for a new trailmap; time management when you juggle a hundred projects at once; how to start a trailmap company; life before the internet; the virtues of skiing at an organized ski center; the process of creating a trailmap; whether you need to ski a ski area to create a trailmap; why Vista Map produces digital, rather than painted, trailmaps; the toughest thing to get right on a trailmap; how the Vista Map system simplifies map updates; converting a winter map to summer; why trailmaps are rarely drawn to real-life scale; creating and modifying trailmaps for complex, sprawling mountains like Vail, Stowe, and Killington; updating Loon’s map for the recent South Peak expansion; making big things look small at Mt. Shasta; Mt. Rose and when insets are necessary; why small ski areas “deserve a great map”; and thoughts on the slow death of the paper trailmap.

Why I thought that now was a good time for this interview

Technology keeps eating things that I love. Some of them – CDs, books, event tickets, magazines, newspapers – are easier to accept. Others – childhood, attention spans, the mainstreaming of fringe viewpoints, a non-apocalyptic social and political environment, not having to listen to videos blaring from passengers’ phones on the subway – are harder. We arrived in the future a while ago, and I’m still trying to decide if I like it.

My pattern with new technology is often the same: scoff, resist, accept, forget. But not always. I am still resisting e-bikes. I tried but did not like wireless headphones and smartwatches (too much crap to charge and/or lose). I still read most books in print and subscribe to whatever quality print magazines remain. I grasp these things while knowing that, like manual transmissions or VCRs, they may eventually become so difficult to find that I’ll just give up.

I’m not at the giving-up point yet on paper trailmaps, which the Digital Bro-O-Sphere insists are relics that belong on our Pet Rectangles. But mountains are big. Phones are small. Right there we have a disconnect. Also paper doesn’t stop working in the cold. Also I like the souvenir. Also we are living through the digital equivalent of the Industrial Revolution and sometimes it’s hard to leave the chickens behind and go to work in the sweatshop for five cents a week. I kind of liked life on the farm and I’m not ready to let go of all of it all at once.

There are some positives. In general I do not like owning things and not acquiring them to begin with is a good way to have fewer of them. But there’s something cool about picking up a trailmap of Nub’s Nob that I snagged at the ticket window 30 years ago and saying “Brah we’ve seen some things.”

Ski areas will always need trailmaps. But the larger ones seem to be accelerating away from offering those maps on sizes larger than a smartphone and smaller than a mountaintop billboard. And I think that’s a drag, even as I slowly accept it.

Podcast Notes

On Highmount Ski Center

Milliken grew up skiing in the Catskills, including at the now-dormant Highmount Ski Center:

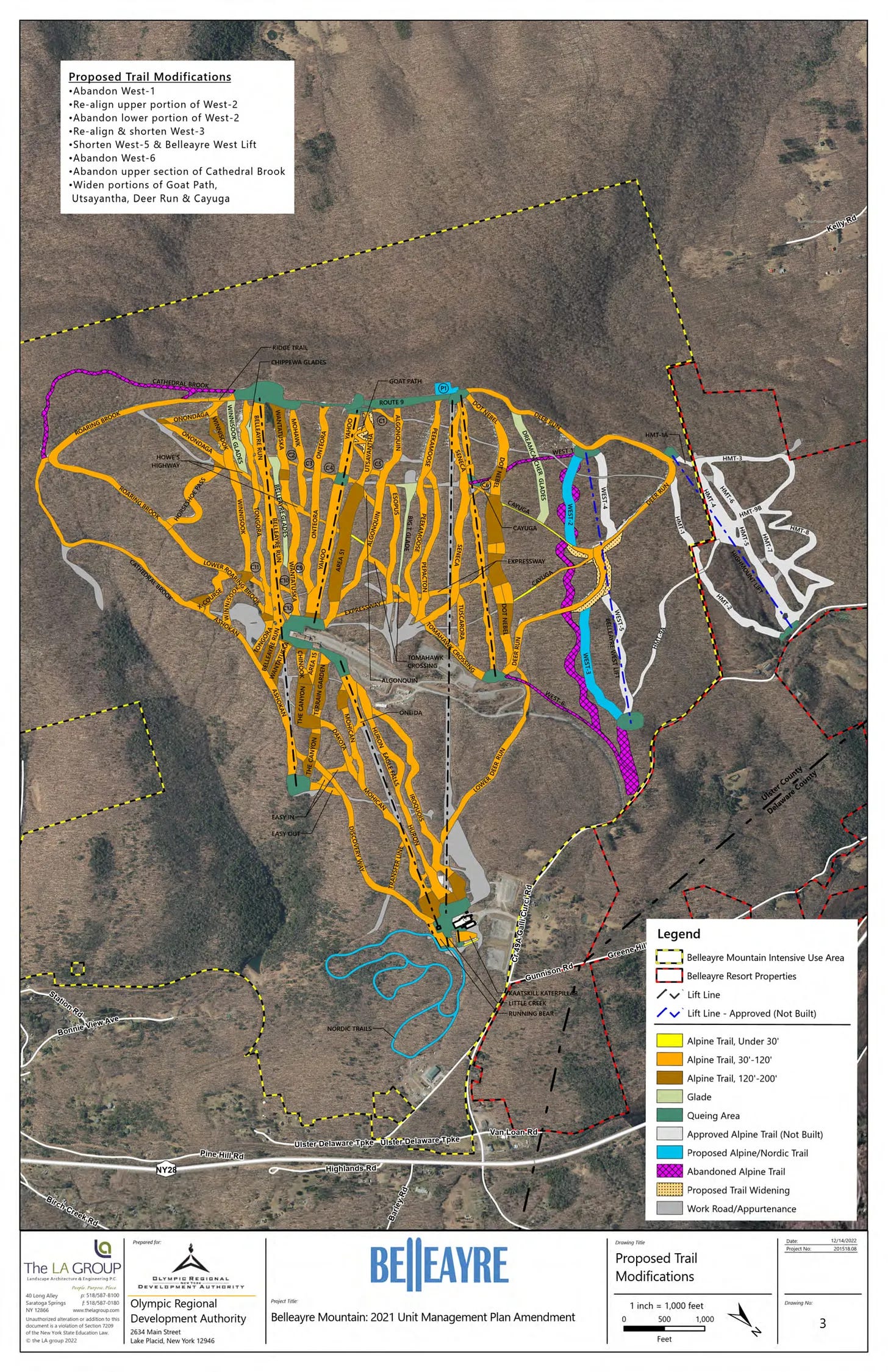

As it happens, the abandoned ski area is directly adjacent to Belleayre, the state-owned ski area that has long planned to incorporate Highmount into its trail network (the Highmount trails are on the far right, in white):

Here’s Belleayre’s current trailmap for context - the Highmount expansion would sit far looker’s right:

That one is not a Vista Map product, but Milliken designed Belleayre’s pre-gondola-era maps:

Belleayre has long declined to provide a timeline for its Highmount expansion, which hinged on the now-stalled development of a privately run resort at the base of the old ski area. Given the amazing amount of money that the state has been funneling into its trio of ski areas (Whiteface and Gore are the other two), however, I wouldn’t be shocked to see Belleayre move ahead with the project at some point.

On the Unicode consortium

This sounds like some sort of wacky conspiracy theory, but there really is a global overlord dictating a standard set of emoji on our phones. You can learn more about it here.

Maps we talked about

Lookout Pass, Idaho/Montana

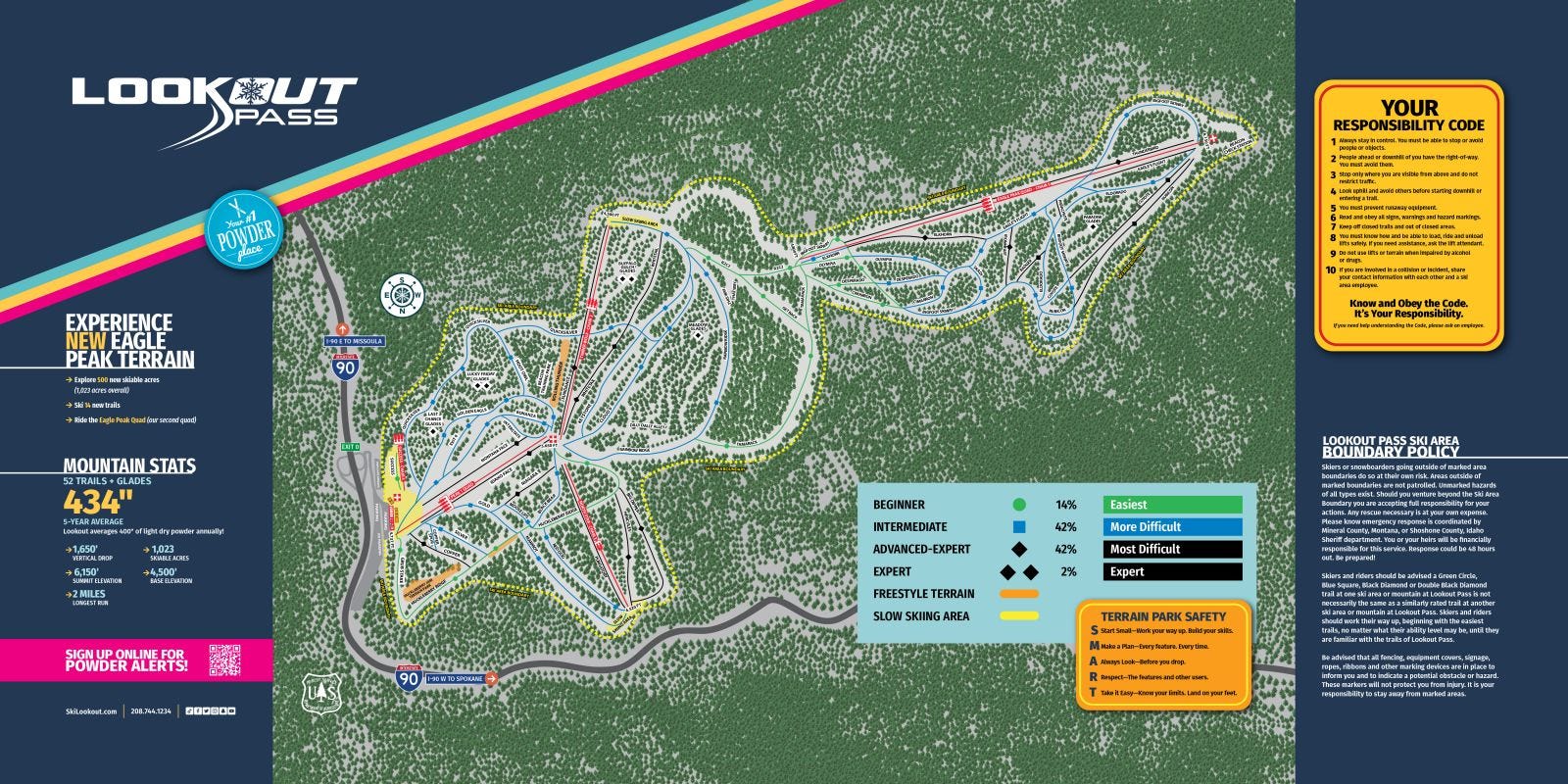

Even before Lookout Pass opened a large expansion in 2022, the multi-sided ski area’s map was rather confusing:

For a couple of years, Lookout resorted to an overhead map to display the expansion in relation to the legacy mountain:

That overhead map is accurate, but humans don’t process hills as flats very well. So, for 2024-25, Milliken produced a more traditional trailmap, which finally shows the entire mountain unified within the context of itself:

Mt. Spokane, Washington

Mt. Spokane long relied on a similarly confusing map to show off its 1,704 acres:

Milliken built a new, more intuitive map last year:

Mt. Rose, Nevada

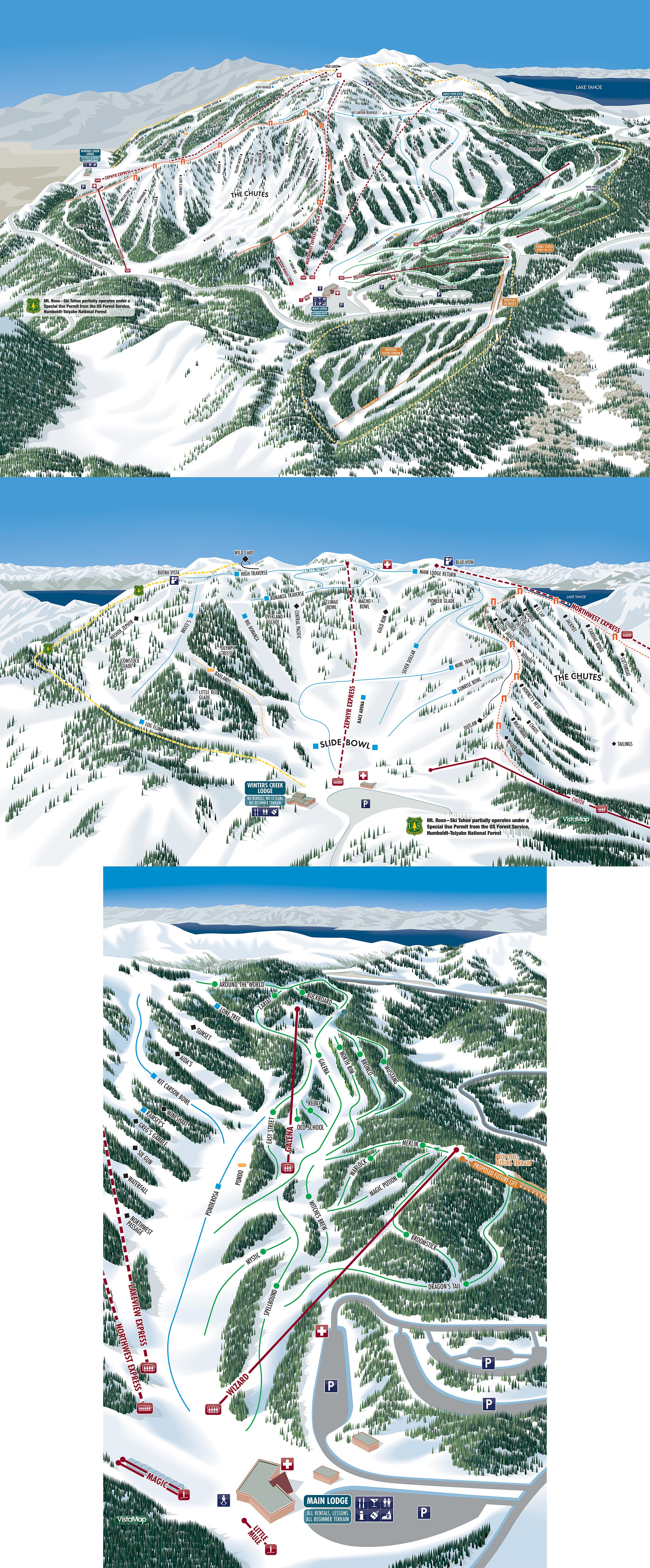

For some mountains, however, Milliken has opted for multiple angles over a single-view map. Mt. Rose is a good example:

Telluride, Colorado

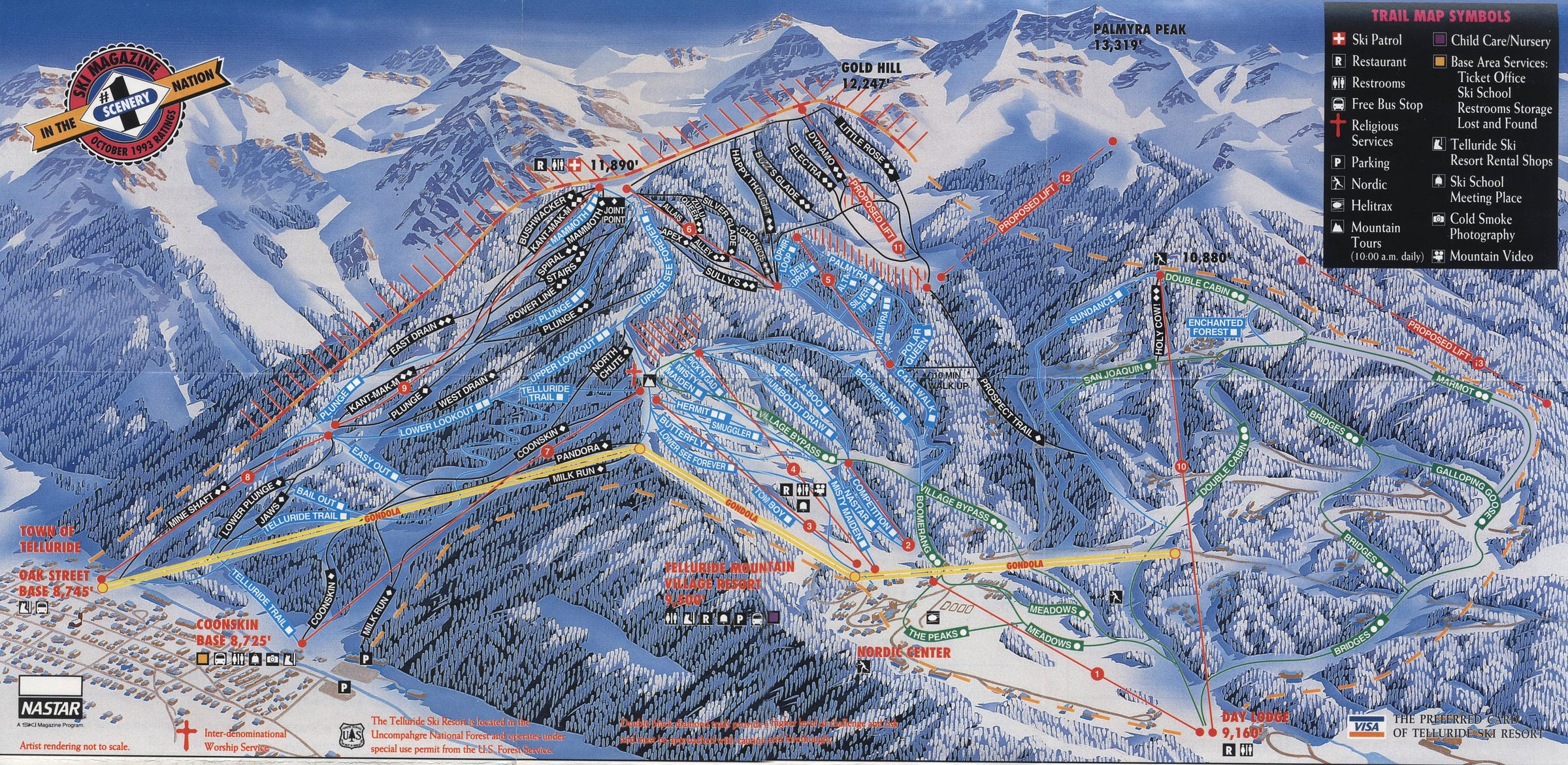

When Milliken decided to become a door-to-door trailmap salesman, his first stop was Telluride. He came armed with this pencil-drawn sketch:

The mountain ended up being his first client:

Gore Mountain, New York

This was one of Milliken’s first maps created with the Vista Map system, in 1994:

Here’s how Vista Map has evolved that map today:

Whiteface, New York

One of Milliken’s legacy trailmaps, Whiteface in 1997:

Here’s how that map had evolved by the time Milliken created the last rendition around 2016:

Sun Valley, Idaho

Sun Valley presented numerous challenges of perspective and scale:

Grand Targhee, Wyoming

Milliken had to design Targhee’s trailmap without the benefit of a site visit:

Vail Mountain, Colorado

Milliken discusses his early trailmaps at Vail Mountain, which he had to manipulate to show the new-ish (at the time) Game Creek Bowl on the frontside:

In recent years, however, Vail asked Milliken to move the bowl into an inset. Here’s the 2021 frontside map:

Here’s a video showing the transformation:

Stowe, Vermont

We use Stowe to discuss the the navigational flourishes of a trailmap compared to real-life geography. Here’s the map:

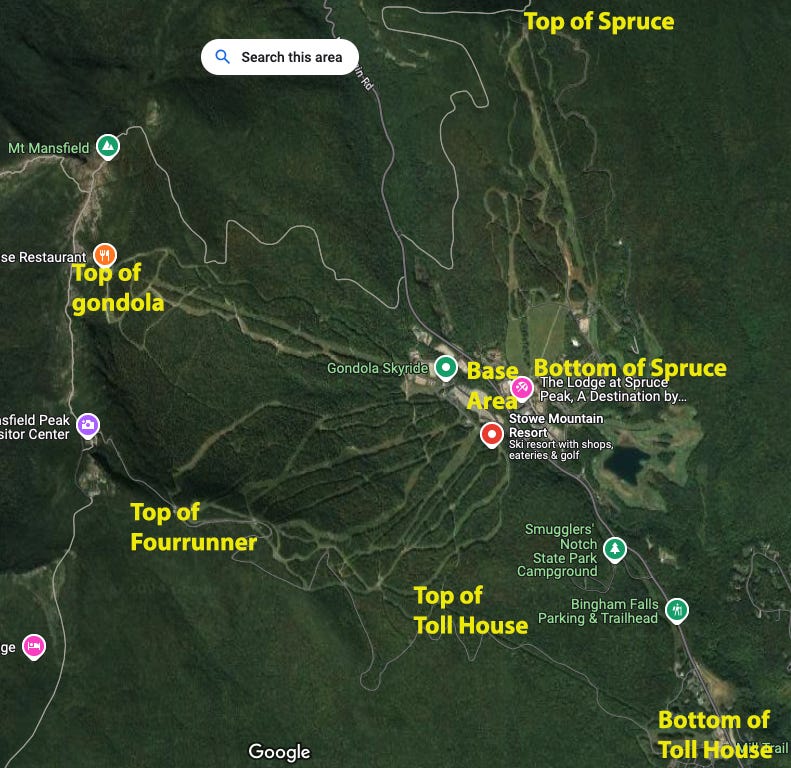

And here’s Stowe IRL, which shows a very different orientation:

Mt. Hood Meadows, Oregon

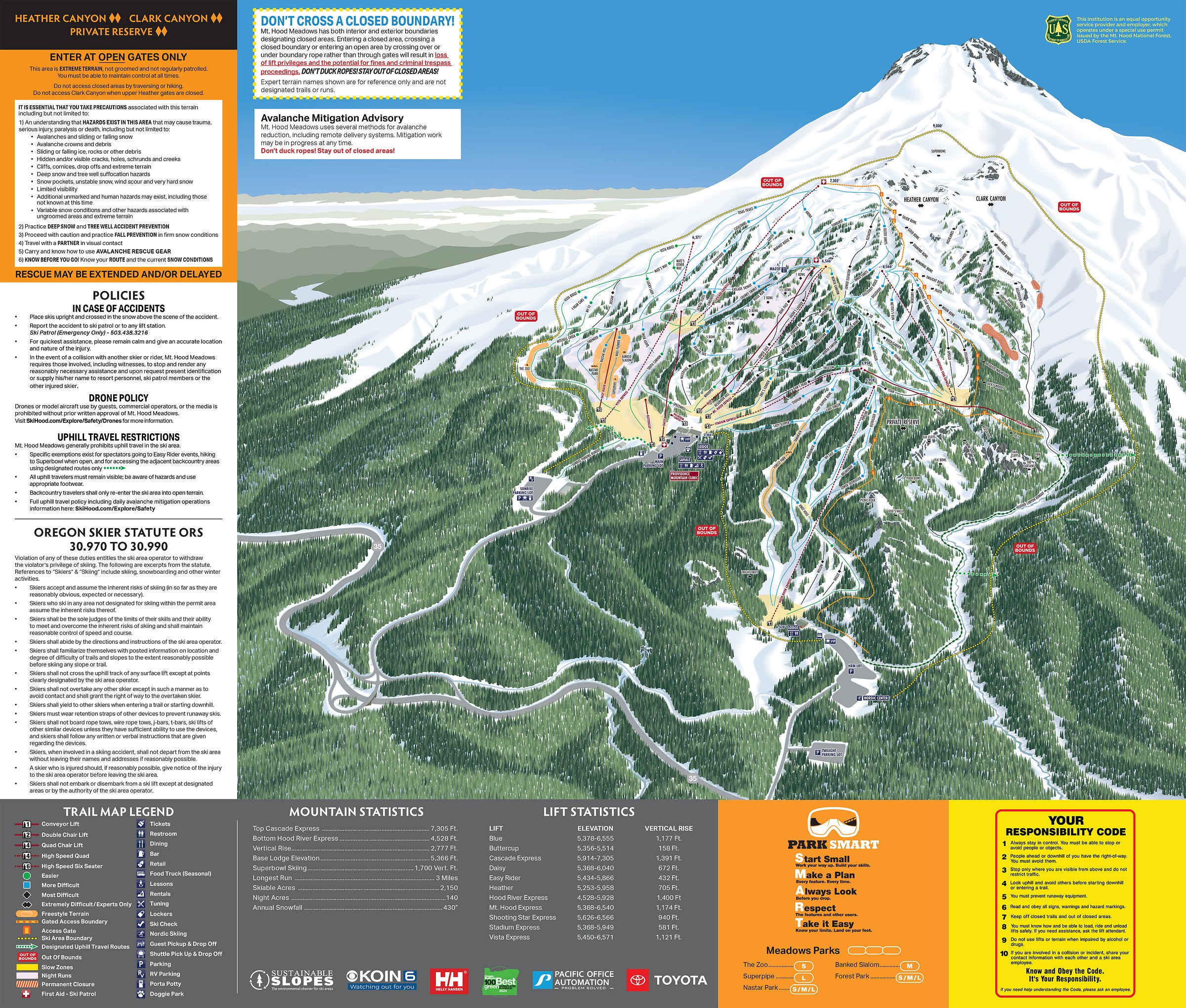

Mt. Hood Meadows also required some imagination. Here’s Milliken’s trailmap:

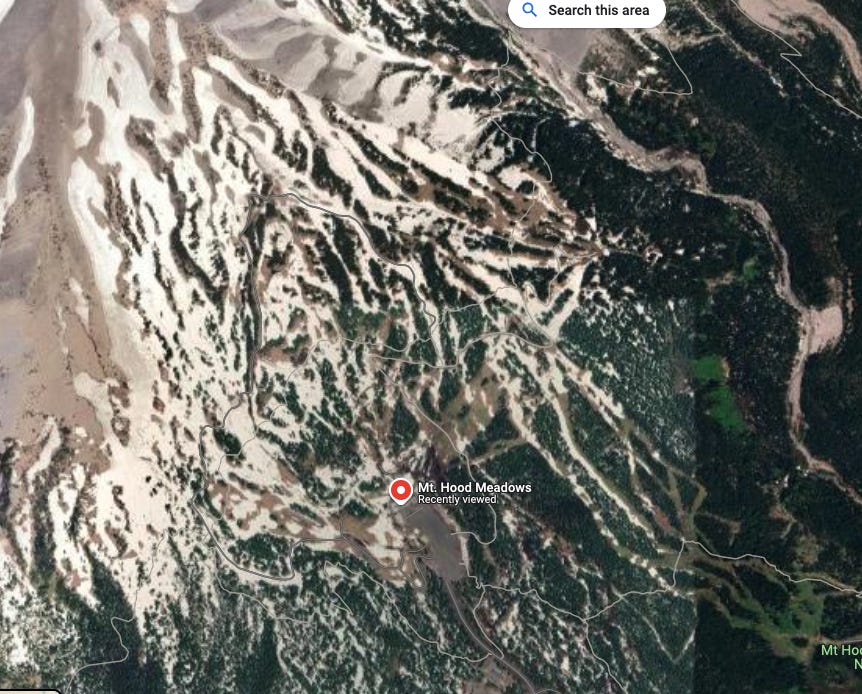

Here’s the real-world overhead view, which looks kind of like a squid that swam through a scoop of vanilla ice cream:

Killington, Vermont

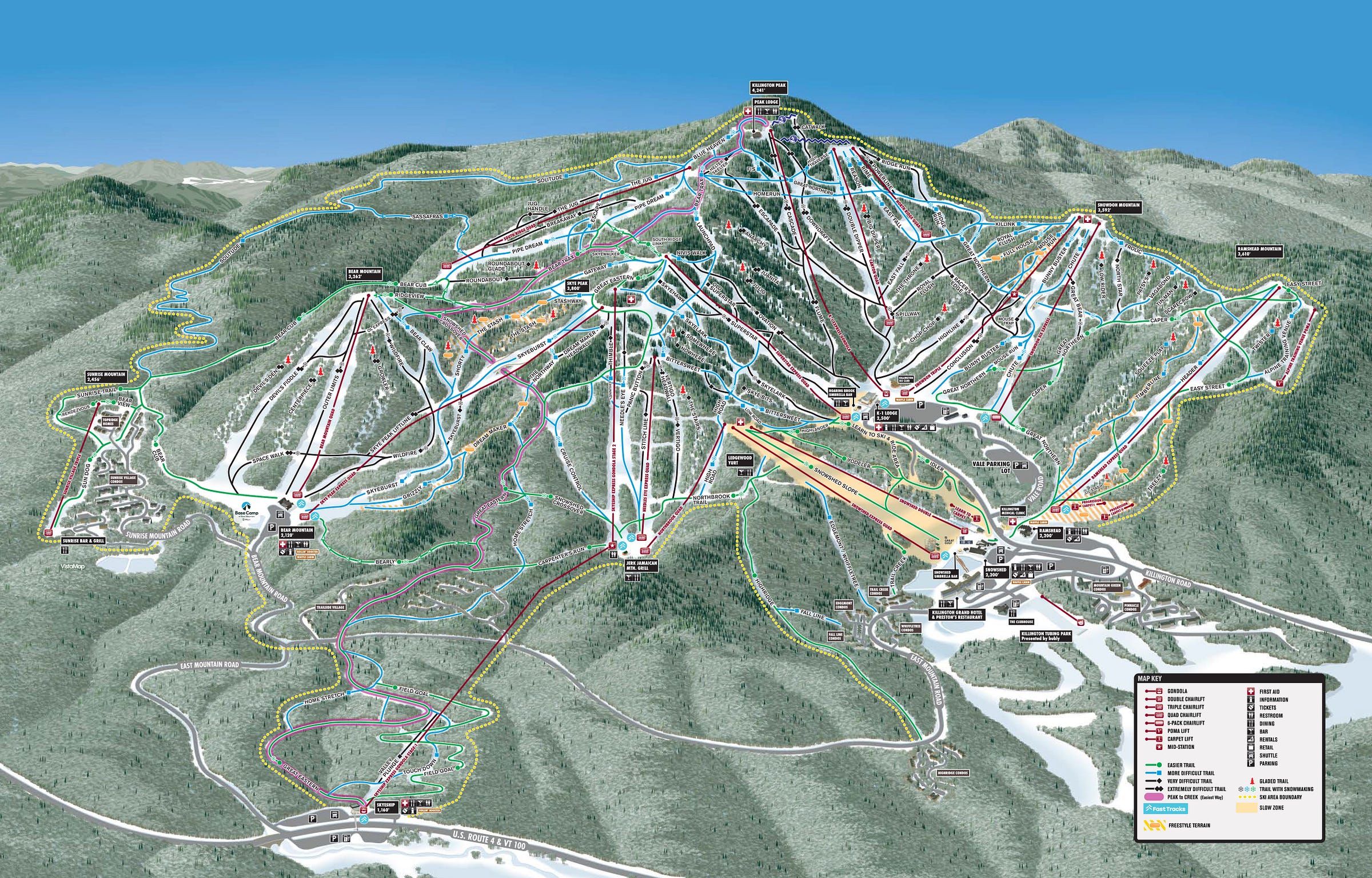

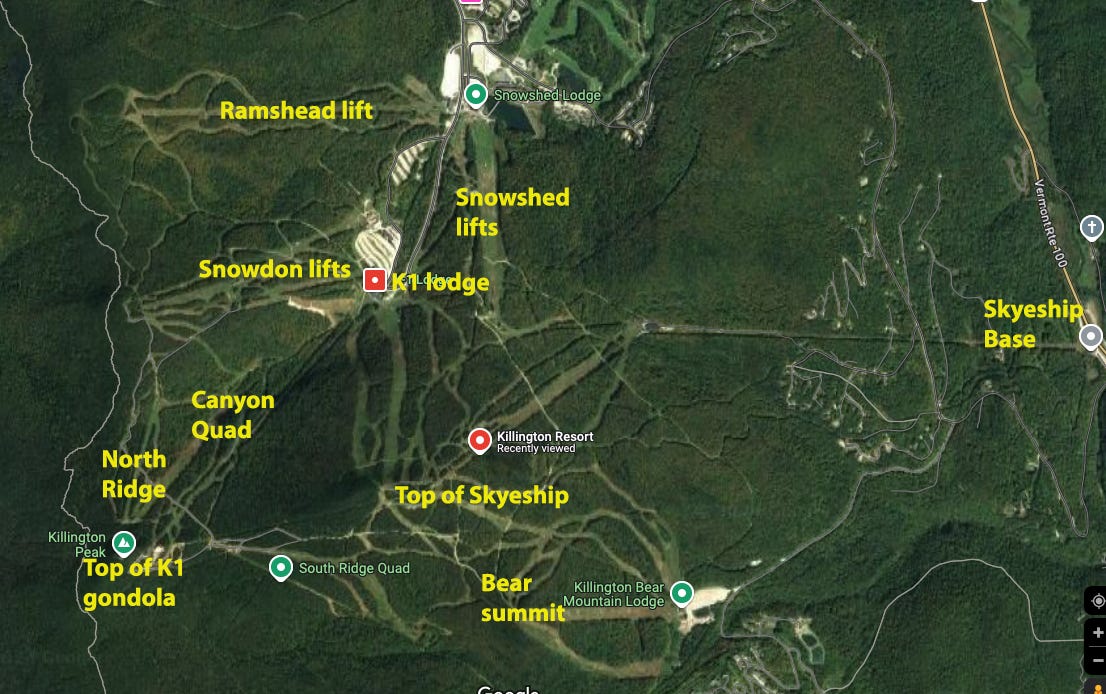

Another mountain that required some reality manipulation was Killington, which, incredibly, Milliken managed to present without insets:

And here is how Killington sits in real life – you could give me a thousand years and I could never make sense of this enough to translate it into a navigable two-dimensional single-view map:

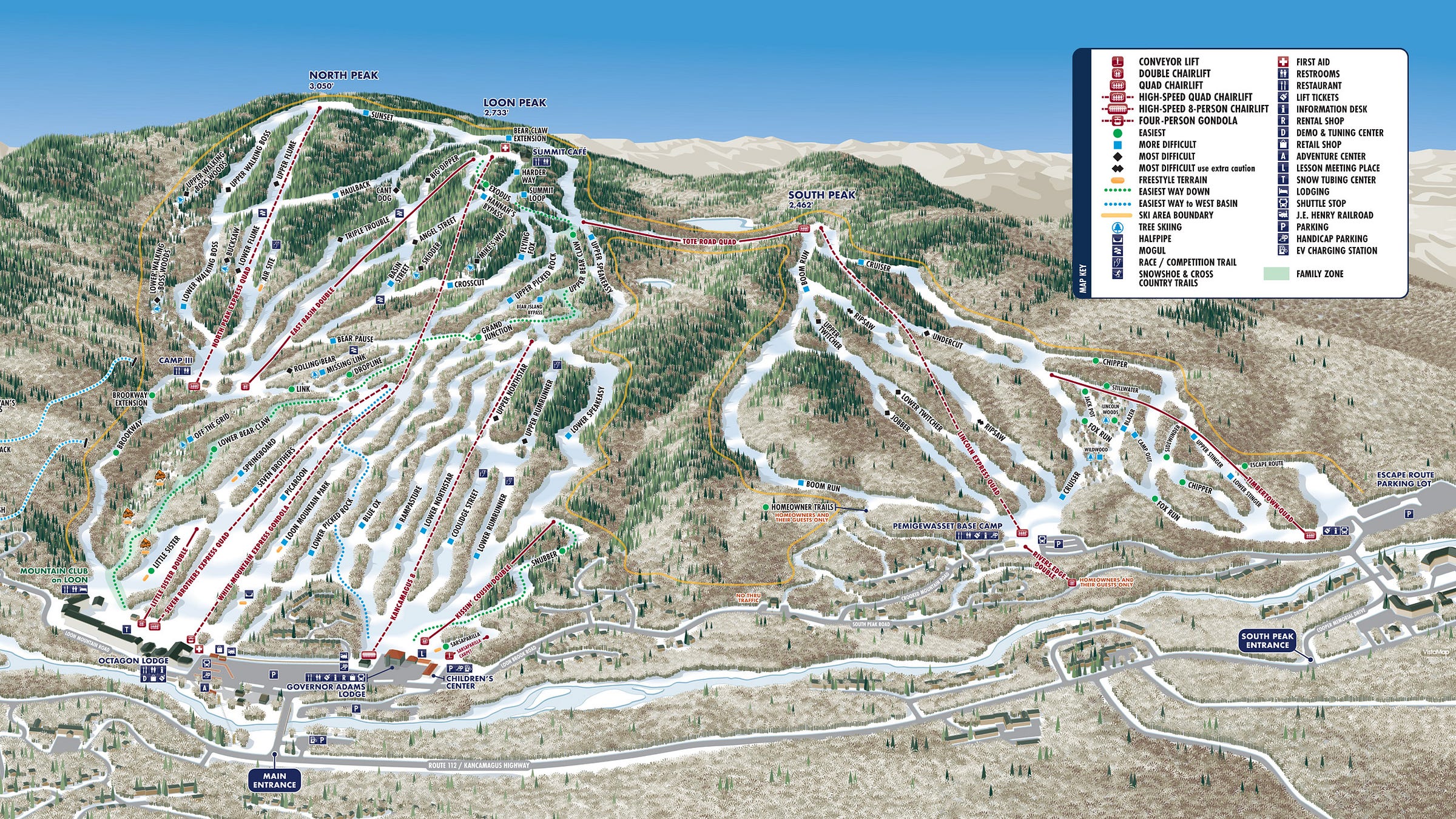

Loon Mountain, New Hampshire

Vista Map has designed Loon Moutnain’s trailmap since around 2019. Here’s what it looked like in 2021:

For the 2023-24 ski season, Loon added a small expansion to its South Peak area, which Milliken had to work into the existing map:

Mt. Shasta Ski Park, California

Sometimes trailmaps need to wildly distort geographic features and scale to realistically focus on the ski experience. The lifts at Mt. Shasta, for example, rise around 2,000 vertical feet. It’s an additional 7,500 or so vertical feet to the mountain’s summit, but the trail network occupies more space on the trailmap than the snowcone above it, as the summit is essentially a decoration for the lift-served skiing public.

Oak Mountain, New York

Milliken also does a lot of work for small ski areas. Here’s 650-vertical-foot Oak Mountain, in New York’s Adirondacks:

Willard Mountain, New York

And little Willard, an 85-acre ski area that’s also in Upstate New York:

Caberfae Peaks, Michigan

And Caberfae, a 485-footer in Michigan’s Lower Peninsula:

On the New York City Subway map

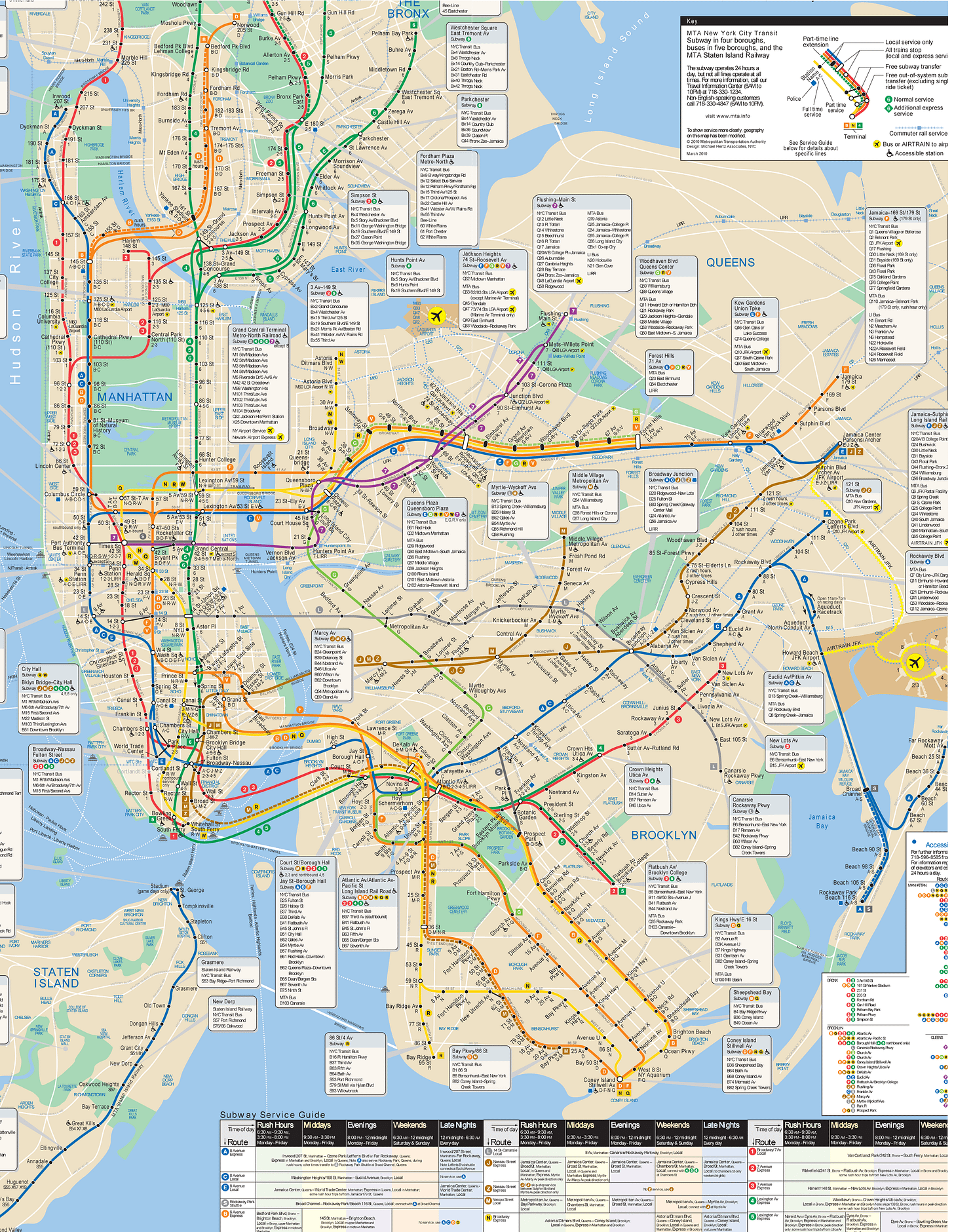

The New York City subway map makes Manhattan look like the monster of New York City:

That, however, is a product of the fact that nearly every line runs through “the city” as we call it. In reality, Manhattan is the smallest of the five boroughs, at just 22.7 square miles, versus 42.2 for The Bronx, 57.5 for Staten Island, 69.4 for Brooklyn, and 108.7 for Queens.

The Storm publishes year-round, and guarantees 100 articles per year. This is article 71/100 in 2024, and number 571 since launching on Oct. 13, 2019.