Who

Matt Davies, General Manager of Cypress Mountain, British Columbia

Recorded on

August 5, 2024

About Cypress Mountain

Click here for a mountain stats overview

Owned by: Boyne Resorts

Located in: West Vancouver, British Columbia

Year founded: 1970

Pass affiliations:

Ikon Pass: 7 days, no blackouts

Ikon Base Pass: 5 days, holiday blackouts

Closest neighboring ski areas: Grouse Mountain (:28), Mt. Seymour (:55) – travel times vary considerably given weather, time of day, and time of year

Base elevation: 2,704 feet/824 meters (base of Raven Ridge quad)

Summit elevation: 4,720 feet/1,440 meters (summit of Mt. Strachan)

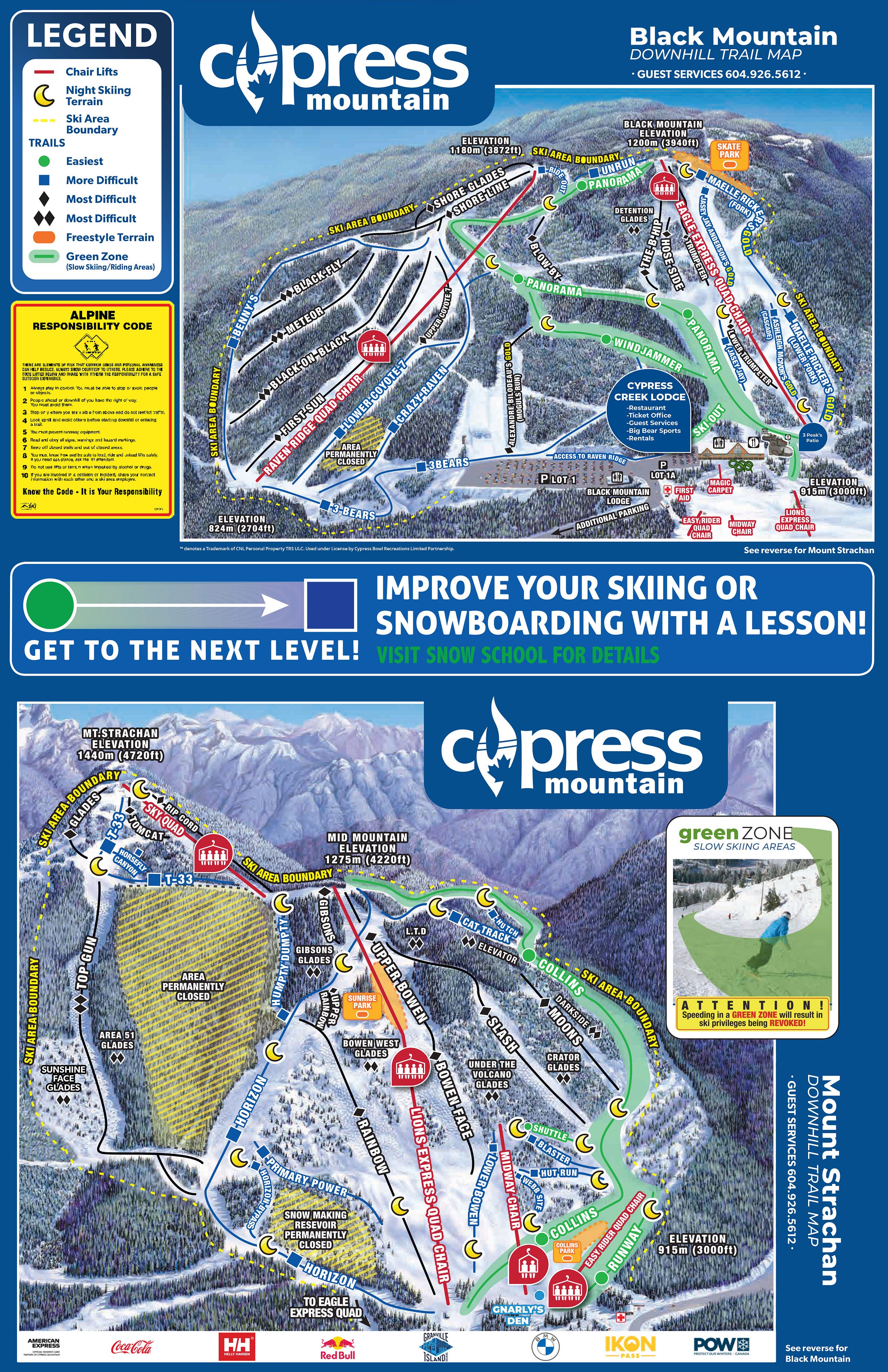

Vertical drop: 2,016 feet/614 meters total | 1,236 feet/377 meters on Black Mountain | 1,720 feet/524 meters on Mt. Strachan

Skiable Acres: 600 acres

Average annual snowfall: 245 inches/622 cm

Trail count: 53 (13% beginner, 43% intermediate, 44% difficult)

Lift count: 7 (2 high-speed quads, 3 fixed-grip quads, 1 double, 1 carpet – view Lift Blog’s inventory of Cypress’ lift fleet)

View historic Cypress Mountain trailmaps on skimap.org.

Why I interviewed him

I’m stubbornly obsessed with ski areas that are in places that seem impractical or improbable: above Los Angeles, in Indiana, in a New Jersey mall. Cypress doesn’t really fit into this category, but it also sort of does. It makes perfect sense that a ski area would sit north of the 49th Parallel, scraping the same snow train that annually buries the mountains from Mt. Bachelor all the way to Whistler. It seems less likely that a 2,000-vertical-foot ski area would rise just minutes outside of Canada’s third-largest city, one known for its moderate climate. But Cypress is exactly that, and offers – along with its neighbors Grouse Mountain and Mt. Seymour – a bite of winter anytime cityfolk want to open the refrigerator door.

There’s all kinds of weird stuff going on here, actually. Why is this little locals’ bump – a good ski area, and a beautiful one, but no one’s destination – decorated like a four-star general of skiing? 2010 Winter Olympics host mountain. Gilded member of Alterra’s Ikon Pass. A piece of Boyne’s continent-wide jigsaw puzzle. It’s like you show up at your buddy’s one-room hunting cabin and he’s like yeah actually I built like a Batcave/wave pool/personal zoo with rideable zebras underneath. And you’re like dang Baller who knew?

What we talked about

Offseason projects; snowmaking evolution since Boyne’s 2001 acquisition; challenges of getting to 100 percent snowmaking; useful parking lot snow; how a challenging winter became “a pretty incredible experience for the whole team”; last winter: el nino or climate change?; why working for Whistler was so much fun; what happened when Vail Resorts bought Whistler – “I don’t think there was a full understanding of the cultural differences between Canadians and Americans”; the differences between Cypress and Whistler; working for Vail versus working for Boyne – “the mantra at Boyne Resorts is that ‘we’re a company of ski resorts, not a ski resort company’”; the enormous and potentially enormously transformative Cypress Village development; connecting village to ski area via aerial lift; future lift upgrades, including potential six-packs; potential night-skiing expansion; paid parking incoming; the Ikon Pass; the 76-day pass guarantee; and Cypress’ Olympic legacy.

Why now was a good time for this interview

Mountain town housing is most often framed as an intractable problem, ingrown and malignant and impossible to reset or rethink or repair. Too hard to do. But it is not hard to do. It is the easiest thing in the world. To provide more housing, municipalities must allow developers to build more housing, and make them do it in a way that is dense and walkable, that is mixed with commerce, that gives people as many ways to move around without a car as possible.

This is not some new or brilliant idea. This is simply how humans built villages for about 10,000 years, until the advent of the automobile. Then we started building our spaces for machines instead of for people. This was a mistake, and is the root problem of every mountain town housing crisis in North America. That and the fact that U.S. Americans make no distinction between the hyper-thoughtful new urbanist impulses described here and the sprawling shitpile of random buildings that are largely the backdrop of our national life. The very thing that would inject humanity into the mountains is recast as a corrupting force that would destroy a community’s already-compromised-by-bad-design character.

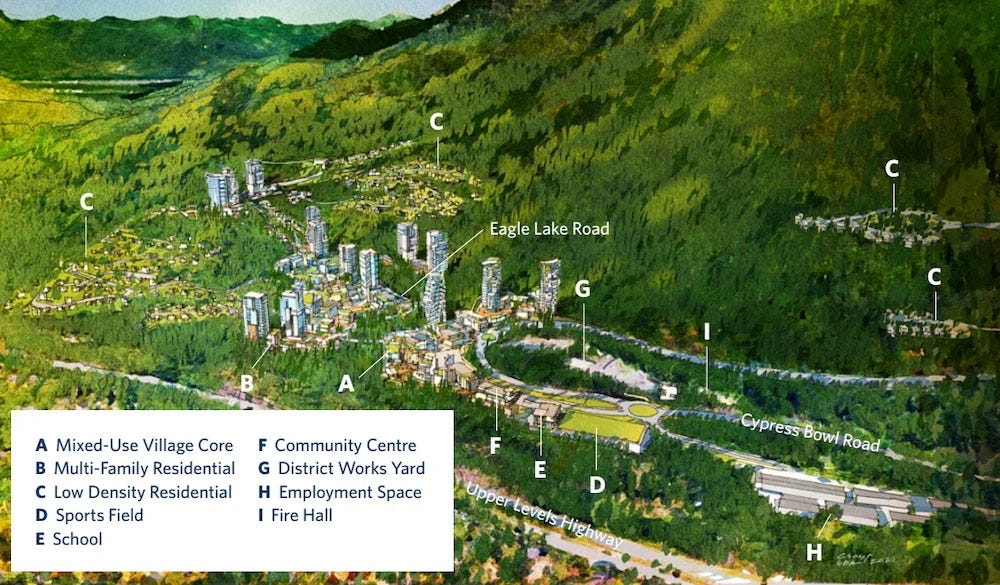

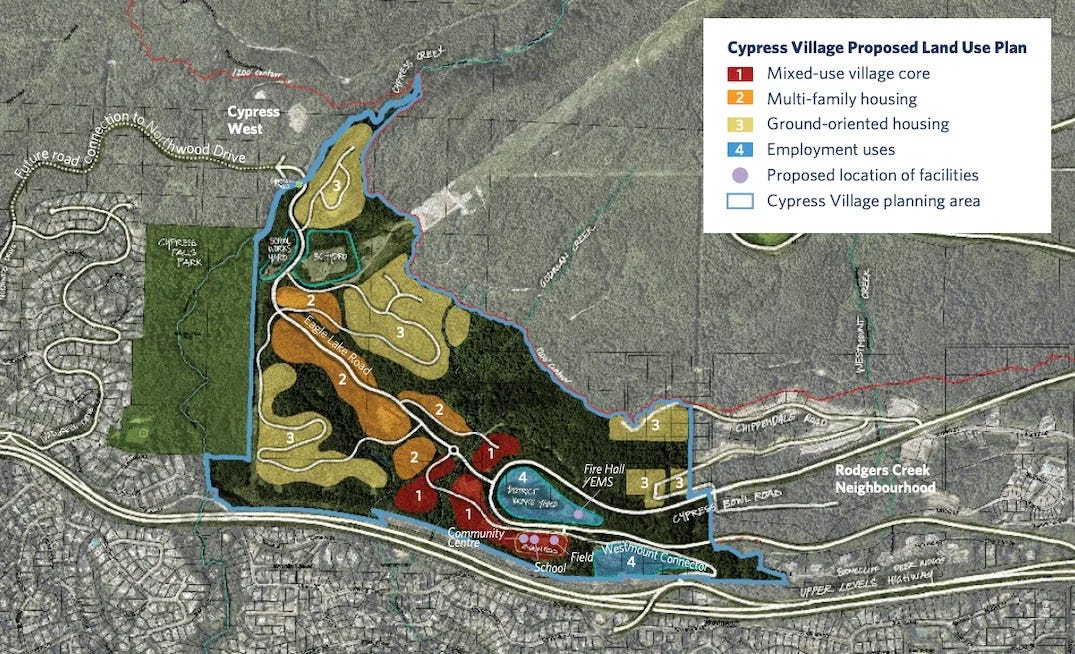

Not that it will matter to our impossible American brains, but Canada is about to show us how to do this. Over the next 25 years, a pocket of raw forest hard against Cypress’ access road will sprout a city of 3,711 homes that will house thousands of people. It will be a human-scaled, pedestrian-first community, a city neighborhood dropped onto a mountainside. A gondola could connect the complex to Cypress’ lifts thousands of feet up the mountain – more cars off the road. It would look like this (the potential aerial lift is not depicted here):

Here’s how the whole thing would set up against the mountain:

And here’s what it would be like at ground level:

Like wow that actually resembles something that is not toxic to the human soul. But to a certain sort of Mother Earth evangelist, the mere suggestion of any sort of mountainside development is blasphemous. I understand this impulse, but I believe that it is misdirected, a too-late reflex against the subdivision-off-an-exit-ramp Build-A-Bungalow mentality that transformed this country into a car-first sprawlscape. I believe a reset is in order: to preserve large tracts of wilderness, we should intensely develop small pieces of land, and leave the rest alone. This is about to happen near Cypress. We should pay attention.

More on Cypress Village:

West Vancouver Approves ‘Transformational’ Plan for Cypress Village Development - North Shore News

West Vancouver Approves Cypress Village Development with Homes for Nearly 7,000 People - Urbanized

What I got wrong

I said that Cypress had installed the Easy Rider quad in 2021, rather than 2001 (the correct year).

I also said that certain no-ski zones on Vail Mountain’s trailmap were labelled as “lynx habitat.” They are actually labelled as “wildlife habitat.” My confusion stemmed from the resort’s historical friction with the pro-Lynxers.

Why you should ski Cypress Mountain

You’ll see it anyway on your way north to Whistler: the turnoff to Cypress Bowl Road. Four switchbacks and you’re there, to a cut in the mountains surrounded by chairlifts, neon-green Olympic rings standing against the pines.

This is not Whistler and no one will try to tell you that it is, including the guy running the place, who put in two decades priming the machine just up the road. But Cypress is not just a waystation either, or a curiosity, or a Wednesday evening punchcard for Vancouver Cubicle Bro. Two thousand vertical feet is a lot of vertical feet. It often snows here by the Dumpster load. Off the summits, spectacular views, panoramic, sweeping, a jigsaw interlocking of the manmade and natural worlds. The terrain is varied, playful, plentiful. And when the snow settles and the trees fill in, a bit of an Incredible Hulk effect kicks on, as this mild-mannered Bruce Banner of a ski area flexes into something bigger and beefier, an unlikely superhero of the Vancouver heights.

But Cypress is also not a typical Ikon Pass resort: 600 acres, six chairlifts, not a single condo tucked against the hill. It’s a ski area that’s just a ski area. It rains a lot. A busy-day hike up from the most distant parking lot can eat an irrevocable part of your soul (new shuttles this year should help that). Snowmaking, by Boyne standards, is limited, (though punchy for B.C.). The lift fleet, also by Boyne standards, feels merely adequate, rather than the am-I-in-Austria-or-Montana explosive awe that hits you at the base of Big Sky.

To describe a ski area as both spectacular and ordinary feels like a contradiction (or, worse, lazy on my part). But Cypress is in fact both of these things. Lodged in a national park, yet part of Vancouver’s urban fabric. Brown-dirt trails in February and dang-where’d-I-leave-my-giraffe deep 10 days later. Just another urban ski area, but latched onto a pass with Aspen and Alta, a piece of a company that includes Big Sky and Big Cottonwood and a pair of New England ski areas that dwarf their Brother Cypress. A stop on the way north to Whistler, but much more than that as well.

Podcast Notes

On the 2010 Winter Olympics

A summary of Cypress’ Olympic timeline, from the mountain’s history page:

On Whistler Blackcomb

We talk quite a bit about Whistler, where Davies worked for two decades. Here’s a trailmap so you don’t have to go look it up:

On animosity between the merger of Whistler and Blackcomb

I covered this when I hosted Whistler COO Belinda Trembath on the podcast a few months back.

On neighbors

Cypress is one of three ski areas seated just north of Vancouver. The other two are Grouse Mountain and Mt. Seymour, which we allude to briefly in the podcast. Here are some visuals:

On Boyne’s building binge

I won’t itemize everything here, but over the past half decade or so, Boyne has leapt ahead of everyone else in North American in adoption of hyper-modern lift technology. The company operates all five eight-place chairlift in the United States, has built four advanced six-packs, just built a rocketship-speedy tram at Big Sky, has rebuilt and repurposed four high-speed quads within its portfolio, and has upgraded a bucketload of aging fixed-grip chairs. And many more lifts, including two super-advanced gondolas coming to Big Sky, are on their way.

On Sunday River’s progression carpets

This is how carpets ought to be stacked – as a staircase from easiest to hardest, letting beginners work up their confidence with short bursts of motion:

On side-by-side carpets

Boyne has two of these bad boys, as far as I know – one at Big Sky, and one at Summit at Snoqualmie, both installed last year. Here’s the Big Sky lift:

On Ikon resorts in B.C. and proximity to Cypress

While British Columbia is well-stocked with Ikon Pass partners – Revelstoke, Red Mountain, Panorama, Sun Peaks – none of them is anywhere near Cypress. The closest, Sun Peaks, is four to five hours under the best conditions. The next closest Ikon Pass partner is The Summit at Snoqualmie, four hours and an international border south – so more than twice the distance as that little place north of Cypress called Whistler.

The Storm publishes year-round, and guarantees 100 articles per year. This is article 56/100 in 2024, and number 556 since launching on Oct. 13, 2019.

Share this post