Can Vail Revive the Epic Pass by Fixing the Lift Ticket?

As the ski giant sells fewer Epic Passes for the second consecutive year and its western resorts struggle, signals of a revival grow stronger

Last week, Vail Resorts officially closed out its 2025-26 Epic Pass sales period with disappointing news: for the second consecutive year, the company sold fewer Epic Passes than it had for the previous winter.

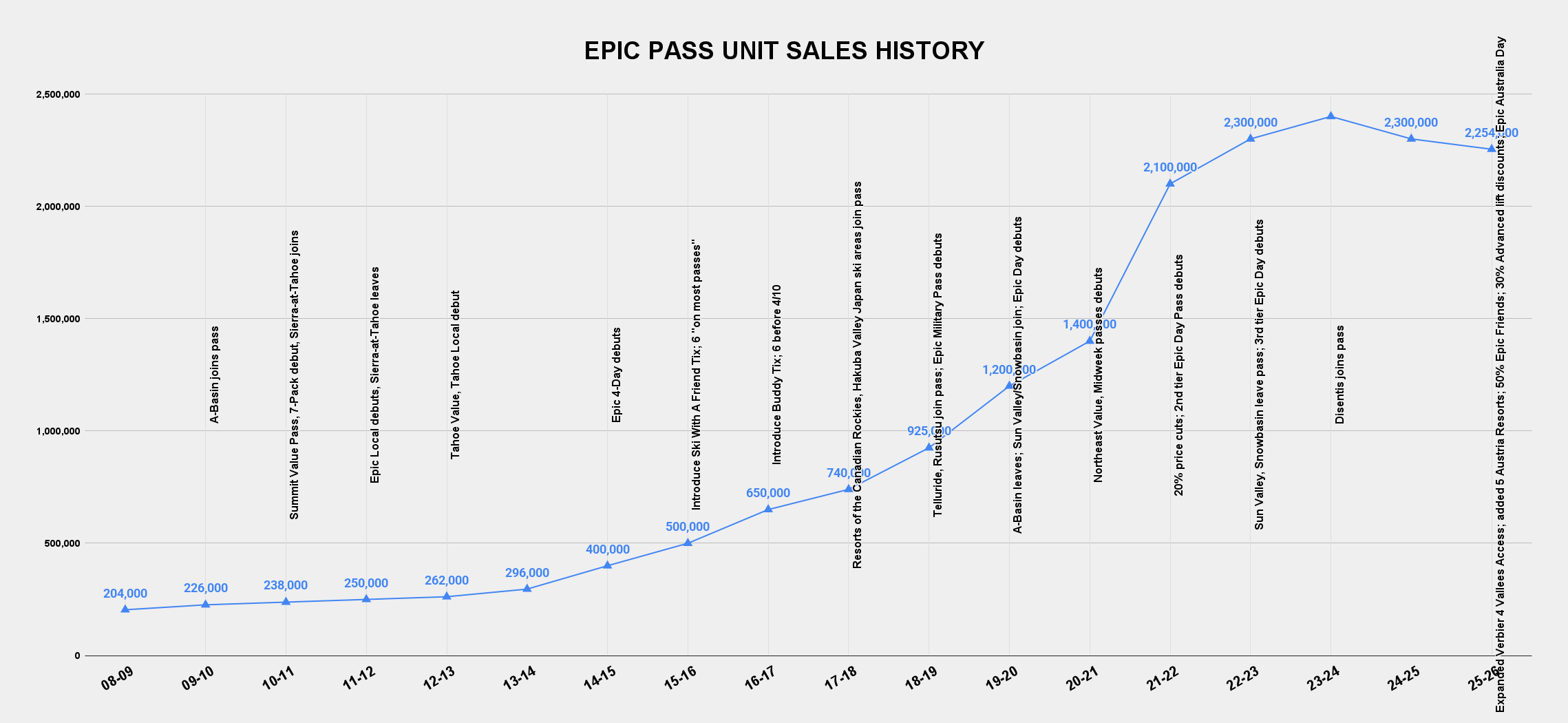

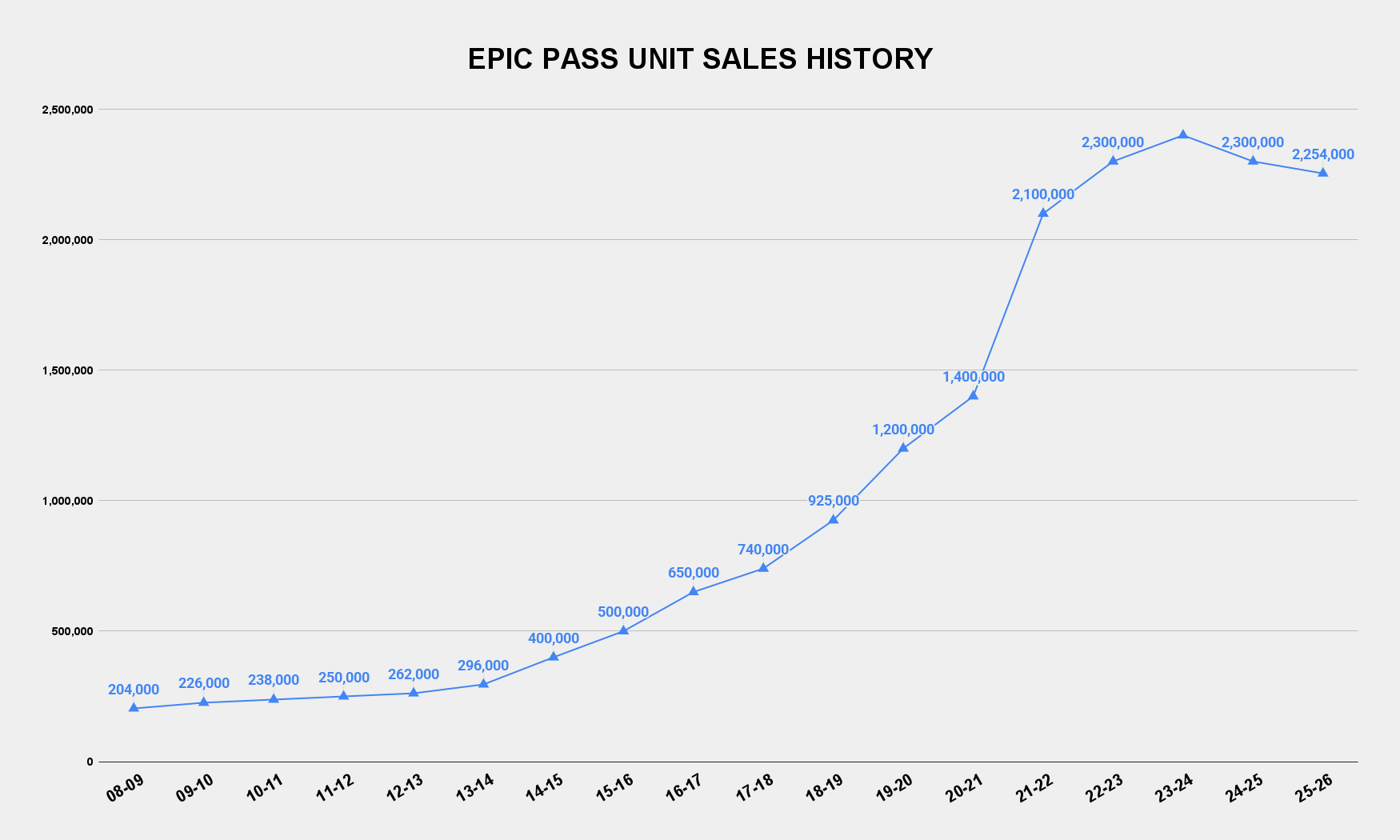

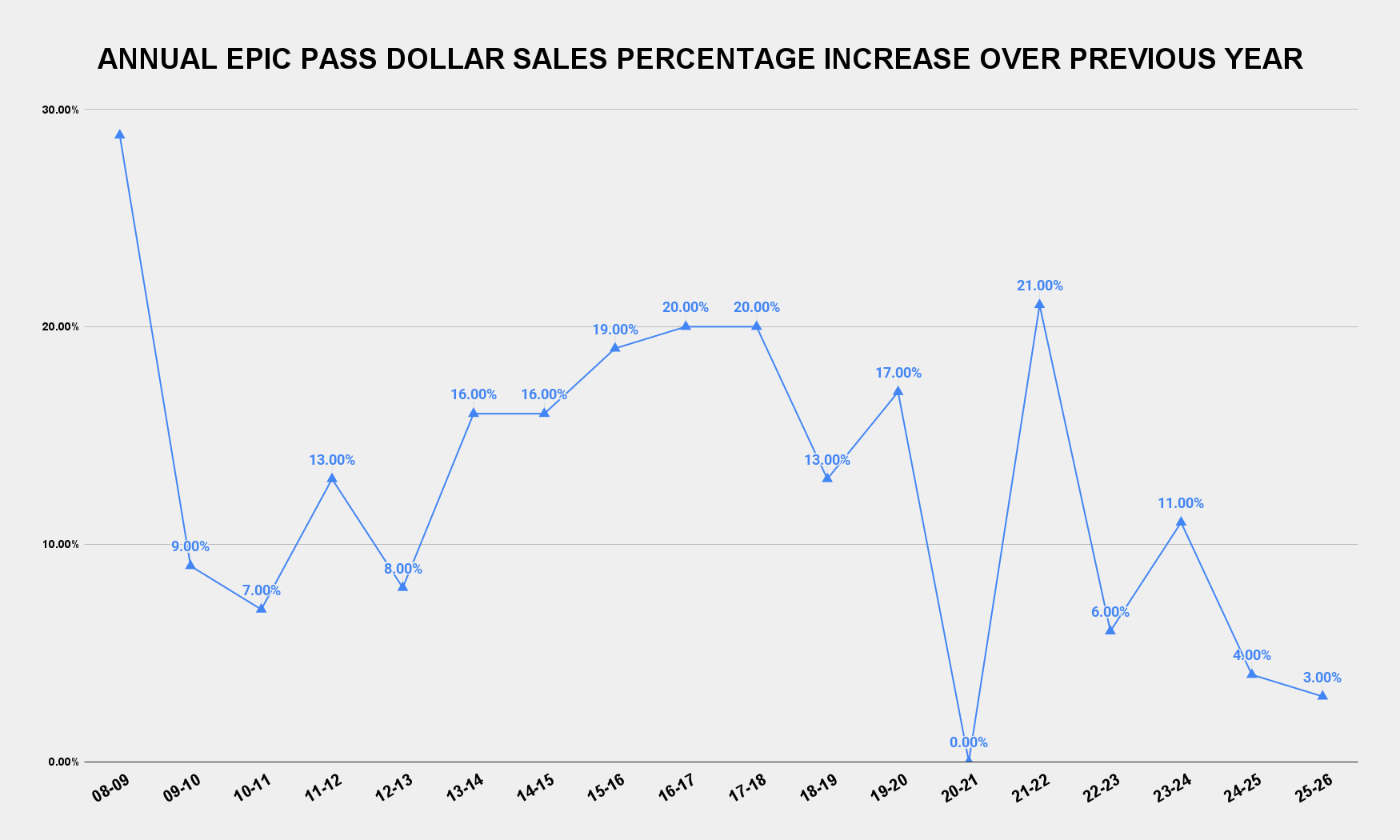

Season-to-season income schizophrenia is normal in skiing. But the Epic Pass, introduced in 2008 with a mostly pre-snowfall sales period, was supposed to fix that by decoupling lift ticket revenue from nature’s inconsistent storm cycles. And for a long time, it worked. As Vail rolled up a global portfolio of ski areas, the company sold more Epic Passes each year from 2009 to 2024. Sales went especially nuclear following a 20 percent price cut for the 2021-22 winter:

More than two million Epic Passes is still a lot of Epic Passes. But for a publicly traded company that had surprised Wall Street by repositioning a niche, weather-dependent industry as a surprise growth opportunity, back-to-back annual unit sales declines make a disappointing trend. And one that likely cost former Vail Resorts CEO Kirsten Lynch her job. Nearly four years after stepping down, former CEO Rob Katz, who had led Vail Resorts’ rise from regional operator to global SuperCo, returned in May to his former role, with a mission of stopping the Epic Avalanche.

May was already too late to meaningfully boost the 2025-26 Epic Pass sales cycle. Vail did report a post-Labor Day Epic Pass sales spike, but the same thing happened last year. And while pass sales dollars increased even as unit sales declined, the three percent uptick was the smallest ever aside from the credit-for-unused-passes-depressed 2020-21 cycle.

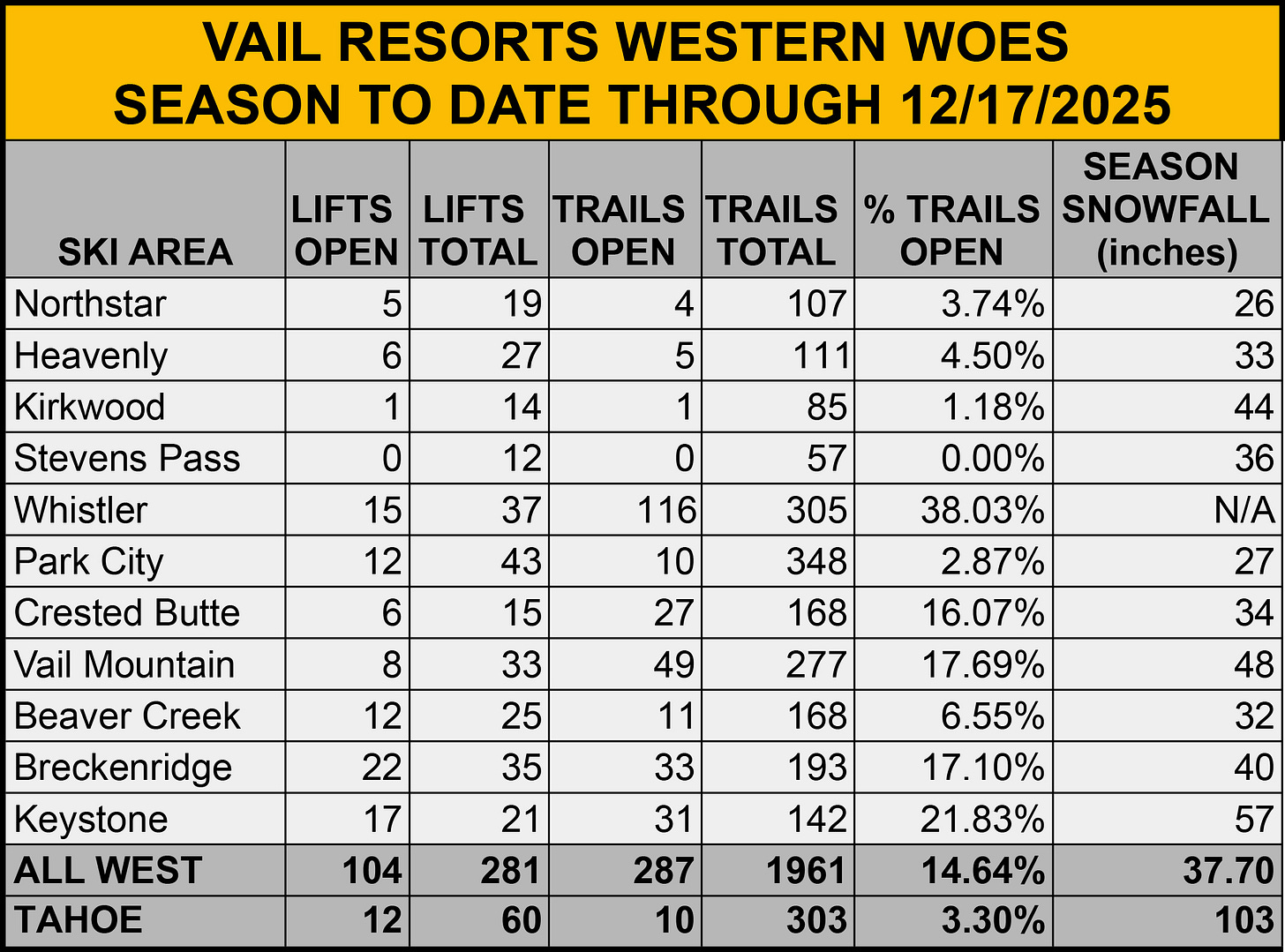

Meanwhile, winter is slow-rolling into western North America. As of Wednesday, just 14.6 percent of trails were open across Vail’s 11 western ski areas. A grand total of 10 of 303 trails were live across the 10,270 combined acres of the company’s three Lake Tahoe resorts: Heavenly (5/111), Northstar (4/107), and Kirkwood (1/85). And Washington State governor Bob Ferguson yesterday said that US 2, the only road to Vail’s Stevens Pass ski area, would be closed for “months” following damage from a monster rainstorm, casting doubt on whether that mountain, Vail’s feeder for the 4 million-person Seattle metropolitan area, could spin lifts at all this winter (I’ve reached out to resort officials for an update and will post any info as soon as I have it).

Christmas is next week. The snow forecast is promising, but if the storm train fizzles out, Vail (and, frankly, every other ski area operator in the West), may be looking at a region-wide holiday disaster that makes last year’s Park City patrol strike look like a disappointing spread at the PTA potluck.

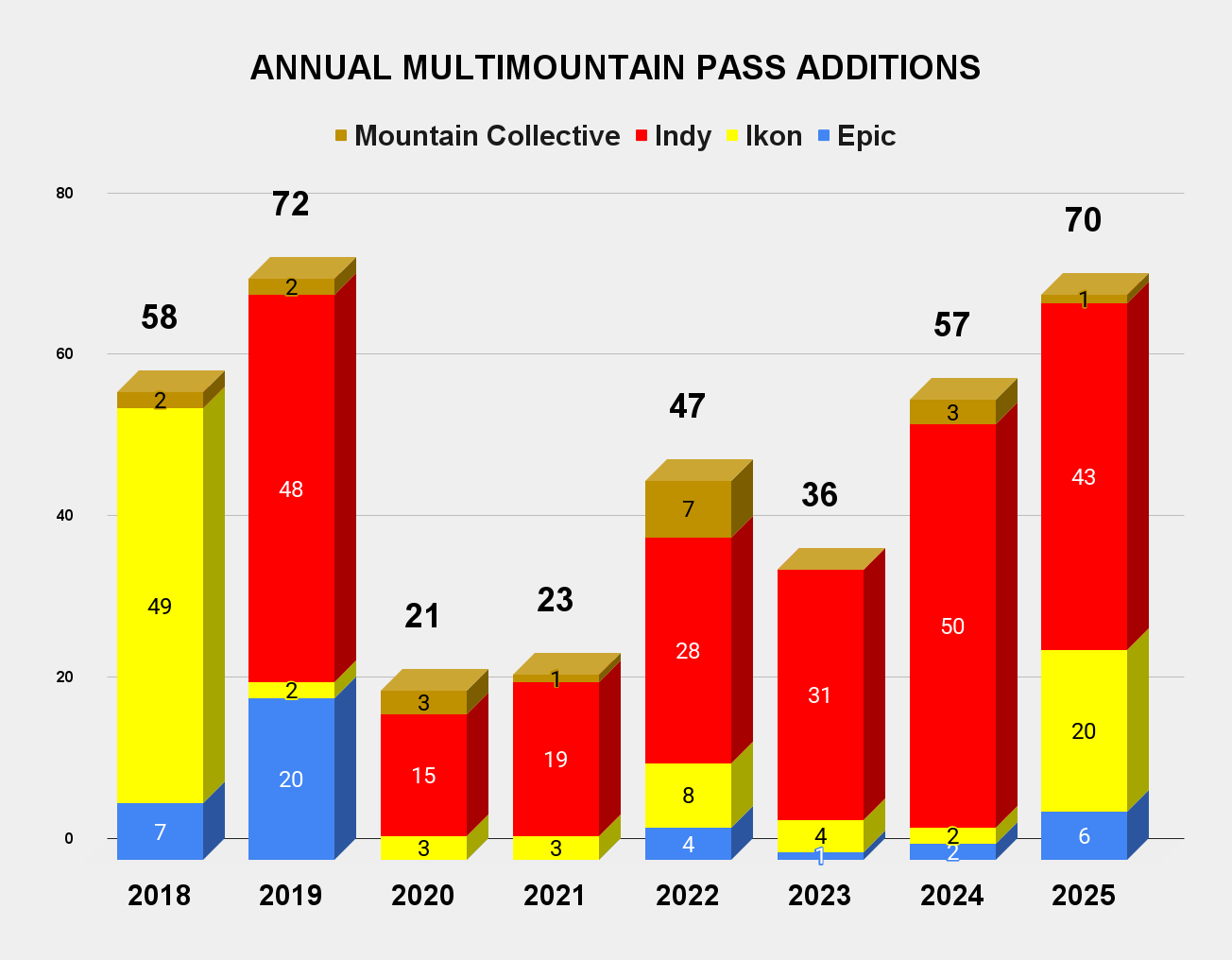

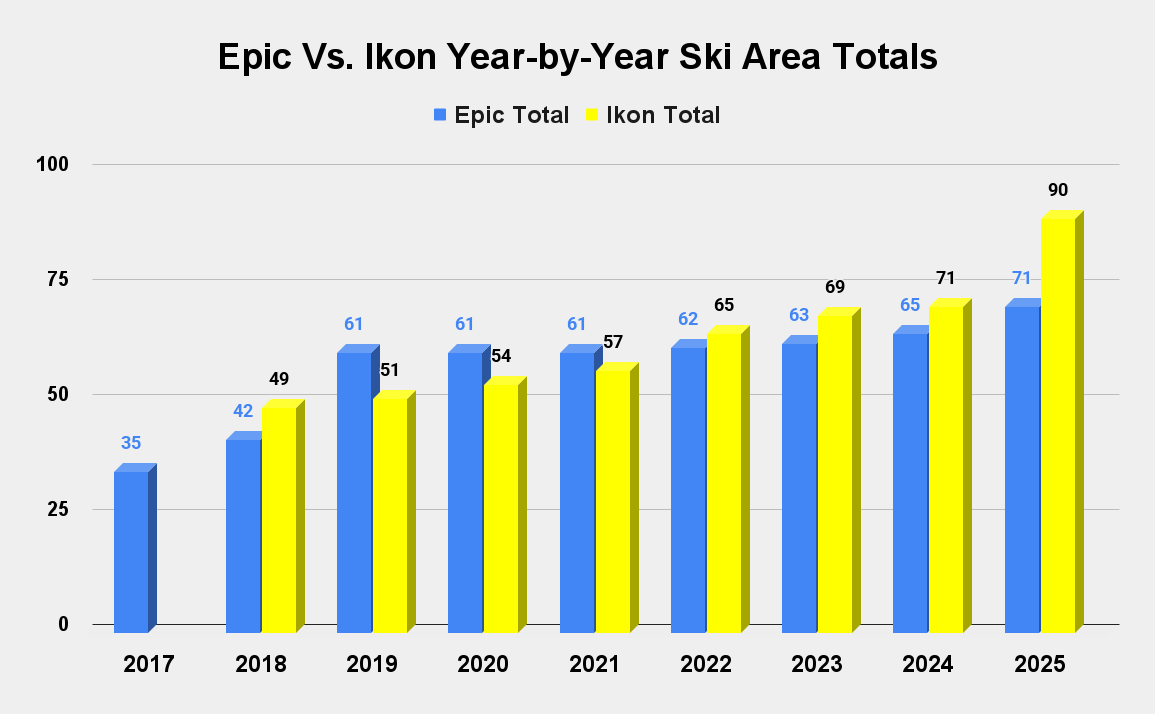

Given that rundown of depressed pass sales and bad ski weather, it will probably sound odd to say that I feel more optimistic about Vail Resorts’ future right now than I have in several years. Six months ago, the onetime ski industry disrupter felt like a dinosaur that was out of ideas. A decade of furious pass and portfolio growth had given way to a regime that seemed detached from concerns over day-to-day ski area operations and preoccupied with the vague promises of Europe and niche smartphone apps. Vail seemed to be both taking its North American passholder base for granted and dismissing the importance of reaching skiers who had not already entered their ecosystem. This retreat from dynamism had occurred as the rest of the U.S. ski industry consolidated under a set of competing passes that cleverly copied Vail’s model while rejecting its excesses by limiting pass sales (Indy), constantly tier-swapping high-volume resorts to manage volume (Ikon), resisting the short-term rush of price cuts (everyone), and regularly adding new partners (again, everyone).

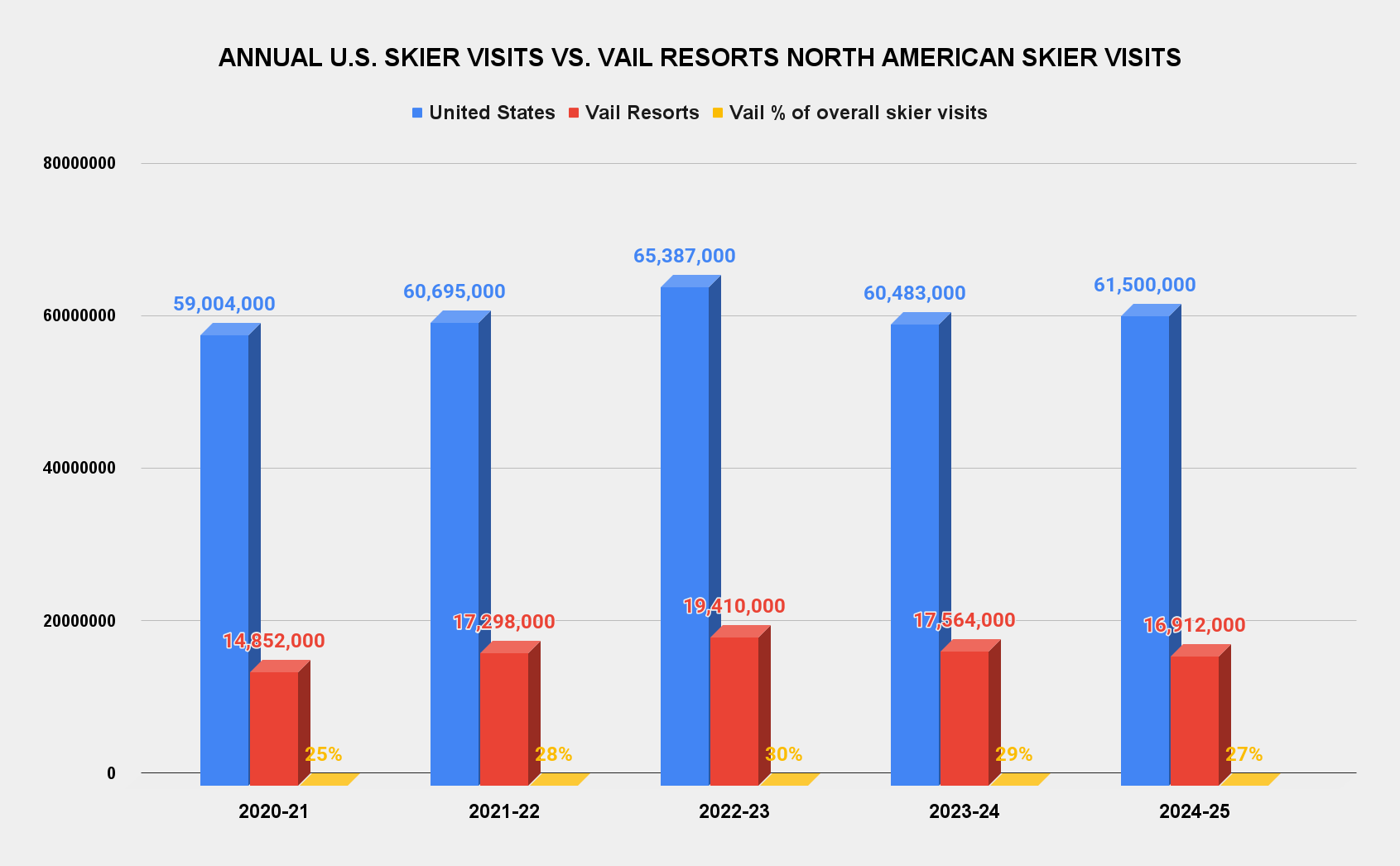

Skiers delivered their verdict over the 2024-25 winter via this scathing statistic: when the National Ski Areas Association reported a 1.7 percent increase in skier visits over the previous year, Vail documented a three percent decrease. The remarkable thing about that 4.7 percent spread between Vail and its competitors is that the company’s 36 resorts typically account for around 25 percent of skier visits to the nation’s 500-ish active ski areas, meaning the non-Vail increase was far greater than 1.7 percent. It all added up to the second-best season on record for the U.S. industry as a whole, and the worst for Vail in four years.

But I believe Vail has bottomed out. This crummy start to western winter won’t help their immediate finances, and the company’s skier visits could slide again this season. Katz’s return, however, matters a lot. This is a company that went bankrupt before Katz arrived and went limp after he left (though, as chairperson of Vail’s board of directors, he never truly left). The animating spirit of Katz’s first CEO tenure, particularly from the Epic Pass’ 2008 arrival through the Covid shutdowns, was one of constant disruption in an industry allergic to change. You can imagine the backroom recoiling at the audacious ideas to chop Vail Mountain’s season pass price by 70 percent, add Midwestern molehills to the roster, kick the door down in a hostile takeover of Park City, or buy rugged off-brand experts’ bumps such as Kirkwood and Crested Butte. Not everything worked, and not everything was a good idea (right?), but the company grew tenfold by market cap from 2006 to 2021, and forced the rest of the industry into a multimountain pass world that changed how skiers accessed the mountains and gave old and aging skiing a new business model other than Gosh-I-hope-it-snows-a-bunch.

What Katz brings back to Vail, then, is less a specific basket of ideas than general permission to take risks, a hard break from the complacency of Lynch’s conservative tenure. The initial focus on lift-ticket discounts is promising not because Vail has conjured up flawless ideas, but because they signal the company’s return to creative problem-solving built on offering a clear value to the skier – in this case, a tangible upfront discount that can be rolled into a down payment for next winter’s Epic Pass.

Whether the discount programs and pass credits will be sufficient to return Epic Pass to growth for 2026-27 is probably not the right question to ask here, because I don’t believe they’ll have to be enough. Over the past six months, Katz has hinted at a broader, drawing-it-as-we-go blueprint for Vail’s revival that will, should history be a reliable guide, actualize itself in Vail’s annual investor deck, a broad strategy document typically released in March. Four elements of Vail’s congealing plan stand out so far: fix the lift ticket, fix the Epic Pass, tie them together with a revamped Turn In Your Ticket program, and enhance the guest experience. Here’s a deeper look at what Vail has done so far in each category, and where they need to go next to spark an Epic Turnaround: