With Unit Sales Falling, Vail’s Epic Pass Is a Trailblazer in Need of a Refresh

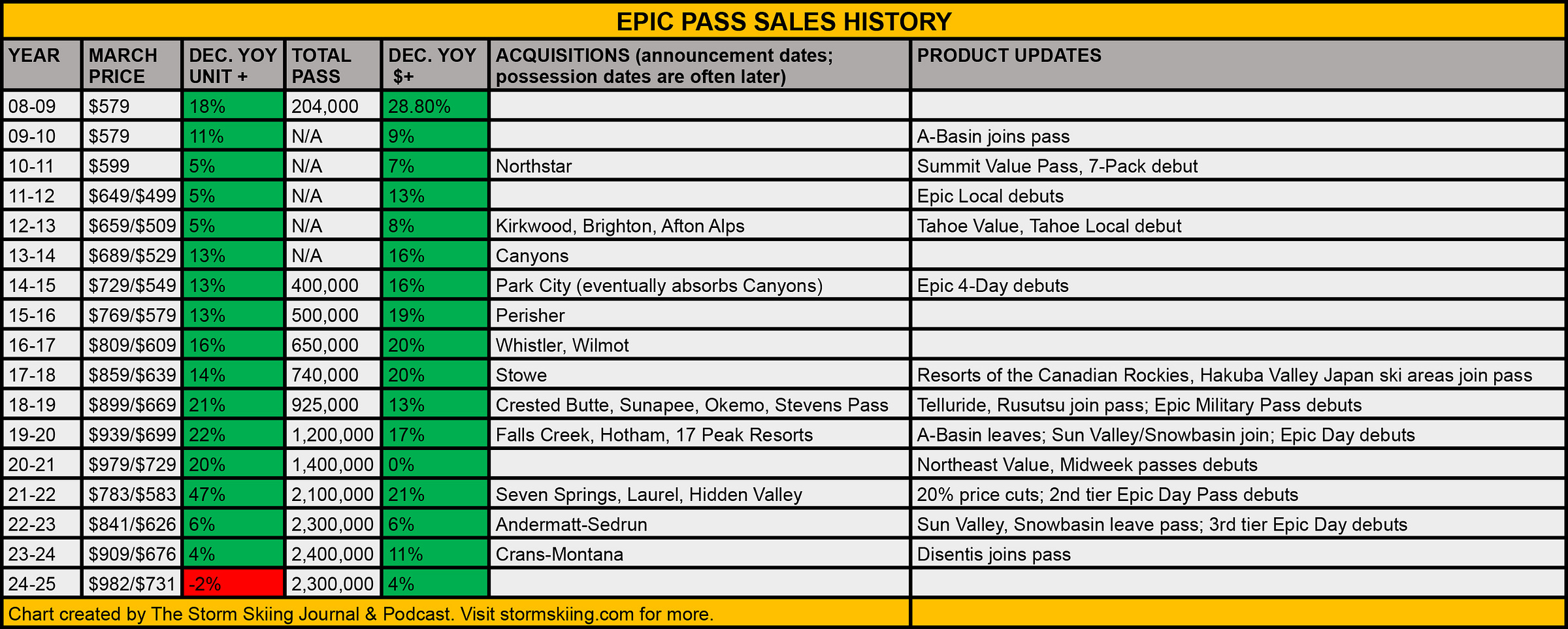

For the first time since the pass’ 2008 debut, Vail Resorts sold fewer 2024-25 Epic Passes than it had for the previous season

What would North American skiing look like today had Vail not launched the Epic Pass in spring 2008?

Without the unifying power of a national pass product, it is unlikely Vail Resorts creeps over the Midwest and East like kudzu. Without the competitive pressures of an unlimited-access pass to some of the largest ski resorts in Colorado and Tahoe, it is unlikely that proud alphas Aspen, Jackson, Alta, and Squaw unite beneath the Mountain Collective banner in 2012. It is similarly unlikely that Boyne, Powdr, and Intrawest join forces on the M.A.X. Pass in 2015. And it is unlikely that the combined braintrust behind M.A.X. and Mountain Collective rally to form Alterra Mountain Company and the Ikon Pass in 2017 and ’18.

Skiing in 2024, in other words, may look a lot like skiing in 2007, or 1987: no national multi-mountain passes, expensive single-mountain season passes, cheap-ish walk-up lift tickets. A pastime that for a century had been localized and clannish, tolerant of but not necessarily welcoming to outsiders, 500 separate forts loosely connected to a couple dozen nationally-known-but-unconnected destination resorts, would likely have remained all of those things.

To which Brobot Bob says “Yay, I reflexively hate everything that is not me and my Brobot Homies.” But the reality of skiing’s Vail-driven multimountain pass revolution is this: soaring on-mountain capital investment, soaring attendance, multimountain season passes priced at half what single-mountain passes cost 15 years ago. Megapasses have stabilized a formerly weather-dependent industry; stitched together national networks that benefit locally focused, independently owned ski areas as much as entity-attached destinations; and muted the locals-rule-tourists-drool big-mountain ethos by making everyone a season passholder. Stability, equality, inclusivity, achieved without saying so.

Problems, too, of course: too much traffic, not enough housing, congested slopes, walk-up lift ticket rates that would embarrass Prada, liftlines that could be mistaken for a wartime border crossing. But the current version of American mountain-town life is not the final draft, and multimountain passes are just one piece of a puzzle that includes the advent of short-term rentals, an overemphasis on automobile-based transit, and social-media yee-hawing that makes tracking and attacking big storms as easy as pouring a bowl of breakfast cereal.

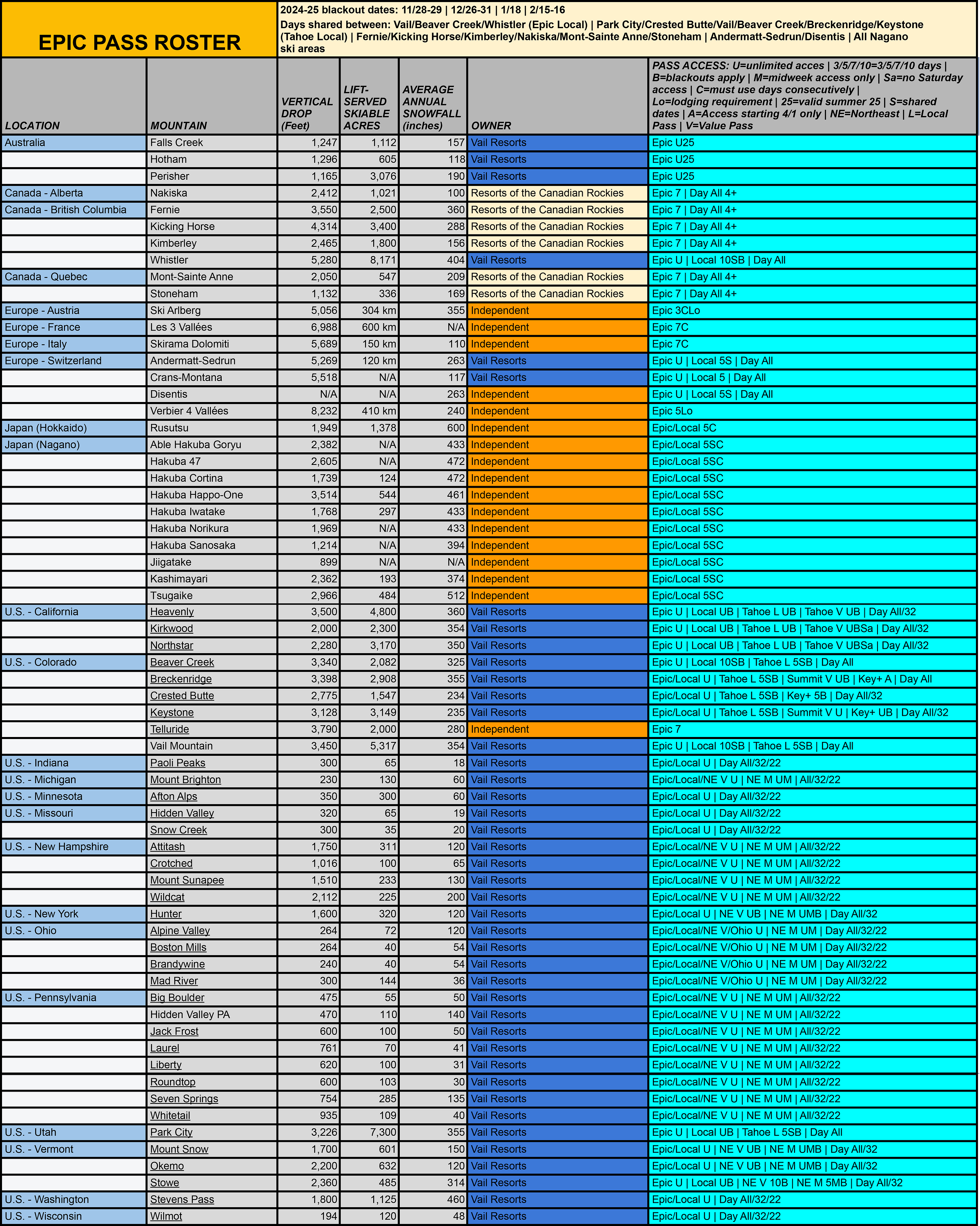

Good or bad or both or neither, Vail’s Epic Pass has transformed North American lift-served skiing. But this industry-changing product, which in the dozen years following its launch added 45 new ski areas, has grown stale. Epic has lost nearly as many ski areas since 2022 (Sun Valley and Snowbasin) as it has added (Andermatt-Sedrun and Crans-Montana, both in Switzerland, and a small ski area in Japan). Ikon offers skiers three times more options in the American West. Vail rarely tweaks access tiers to manage traffic at its most congested mountains, often flooding busy ski areas such as Hunter, Stevens Pass, and Okemo on peak periods. Operations in the Lower Midwest and Mid-Atlantic have been inconsistent, with too-short seasons and frustrated passholders. Upstarts such as the Indy and Power Pass are offering cheaper access to (often) more interesting and less crowded local hills across New England, the Midwest, the Mid-Atlantic, the Pacific Northwest, B.C., and the Southwest.

What was once skiing’s most exciting product is now just another ski pass among many. Nothing underscores this point more than the fact that, after 15 consecutive years of growth, Vail Resorts sold fewer Epic Passes in 2024 than it had in the prior year. While the unit drop was small – just two percent, from 2.4 million 2023-24 passes to 2.3 million this year – and sales dollars still increased by four percent, this is a potentially bad sign for a product that recorded double-digit growth for the nine consecutive years from 2013 to 2021:

Not all is dire in Epic Land. Vail Resorts has achieved its long-stated goal of shifting 75 percent of skier visits to pre-purchased products. The Epic Day Pass is a best-in-class product that has yet to achieve its full potential. And the partner roster, while stagnant for the past few years, is still lights-out, headlined by some of the world’s finest ski areas:

And, frankly, we don’t know that Ikon and Mountain Collective aren’t recording similar sales slides (Indy Pass, which started with microscopic sales in 2019, continues to grow, and a Mountain Capital Partners representative confirmed that sales of their Power Passes increased this year).

But it may be time for an Epic Pass reset. That doesn’t mean changing the core of what the product is, with its top-tier unlimited portfolio-wide access, clever regional variations, compelling hub-and-spoke network, and everyman’s price point. But it does mean rethinking the extent and variety of the partner network, mixing up access tiers, refocusing on the North American market, turbocharging operations at Vail’s smaller ski areas, introducing renewal incentives, and stabilizing resort leadership.

After taking deep looks at Ikon and Mountain Collective, it’s time to dissect Epic to see what’s working and how this once industry-shaking pass can return to earthquake mode: