Willamette Pass Hopes to Double Size, Offer Relief to Strangled Pacific Northwest

This is MCP pulling an MCP

Ya’ll better recognize

Let’s say you are a resident of Eugene, Oregon. The population has exploded by 45 percent over the past 30 years. You are surrounded by people blowing those stupid duck whistles*. Your only beverage choices are Mochalatte craft beer or gluten-free grass-fed carrot milk. You understandably want to get the hell out of town and go skiing for the weekend.

You consider your options. Willamette Pass is the closest ski area to town, less than 90 minutes away. But terrain is limited. Last time you visited, the parking lot hadn’t been plowed and no one was directing traffic. The grooming looked as though someone had just pushed a few boulders downhill to pack the snow. Shockingly, a six-pack rolled toward the summit, but the neighboring triple chair hadn’t been turned on since E.T. was in theaters. The place may average 430 inches of snow per year, but it’s the gas-station hotdog of skiing – you know it will disappoint you before you consume it. So you resign yourself to fighting Planet Ikon at Mount Bachelor, roughly double the drive time around the mountains, or muscling your way up to Hood to take on the armada of invading Portland skiers at Timberline or Meadows. Or you just stay home. At least you can get your toasted seaweed eggs delivered by a dude on a motorbike.

The ski calculus of the Pacific Northwest is broken, especially along the I-5 corridor. While circumstances vary up and down the coast, the basic problem is this: too few ski areas serving a growing population of outdoorsy transplants with bags of tech cash slung over their shoulders and a ski rack-equipped AWD Subaru that they won’t stop talking about. As a result, traffic sucks, liftlines suck, the snow gets tracked out in four seconds, and everyone hates the Ikon Pass (which they also purchase). It’s the Granola Bro Paradox: an influx of people who care deeply about the outdoors are ruining the experience of being in it.

But the Pacific Northwest will not get any new ski areas to help ease congestion. There’s a better chance of a U.S. nuclear arms sale to North Korea than a new ski resort being built, planned, or even suggested within 600 miles of the Pacific Ocean (OK, you can do it in Canada). So the only option to address growing demand is this: expand the size or capacity of the region’s existing ski areas.

This is happening, in slow motion. Vail has built three new quads at Stevens Pass since buying the resort in 2018, replacing two ancient doubles and a triple. Alterra has endlessly tweaked pass offerings, parking plans, and transit options to calm the approach road at Crystal. Boyne is upgrading and adding lifts at Alpental and modernizing its fleet at the sprawling Summit at Snoqualmie ski areas across the interstate. Timberline purchased down-mountain Summit ski area, linked to it with ski-down trails, and plans a super-gondola connecting the two (a shuttlebus serves that purpose for now). Meadows and Bachelor both upgraded important out-of-base lifts to six-packs last summer. Mission Ridge has been planning a big expansion since warriors rode wooly mammoths into battle.

These are all welcome and encouraging improvements. But these ski areas are already-established regional destinations. The Pacific Northwest has needed a new fixer for a while. Someone who was willing to drive past the mansions, get into the blue-collar back hoods, and start fixing up the rust-buckets. When Mountain Capital Partners announced, in late 2022, that they were assuming operation of Willamette Pass, we knew big things were coming. As I wrote at the time:

“…let’s be honest: this transition is objectively and unambiguously good news for Willamette Pass. Everything will change here and fast. MCP’s emphasis is on fixing up infrastructure, on long seasons and snowmaking, on new lifts and refurbished masterplans. … MCP, as the Pacific Northwest is about to discover, is no ordinary operator.”

MCP quickly renovated their new house, adding snowmaking, fixing the parking lot, buying a new snowcat, and reactivating that antique Midway chair. The company also, of course, immediately added the mountain to their knockout Power Pass, which is free for kids under 12 and a bargain for adults (the adult Power Pass Core, which offers unlimited Willamette Pass access with holiday blackouts, was just $299 at early-bird prices; it’s $349 right now). Willamette Pass now resembles a real ski area.

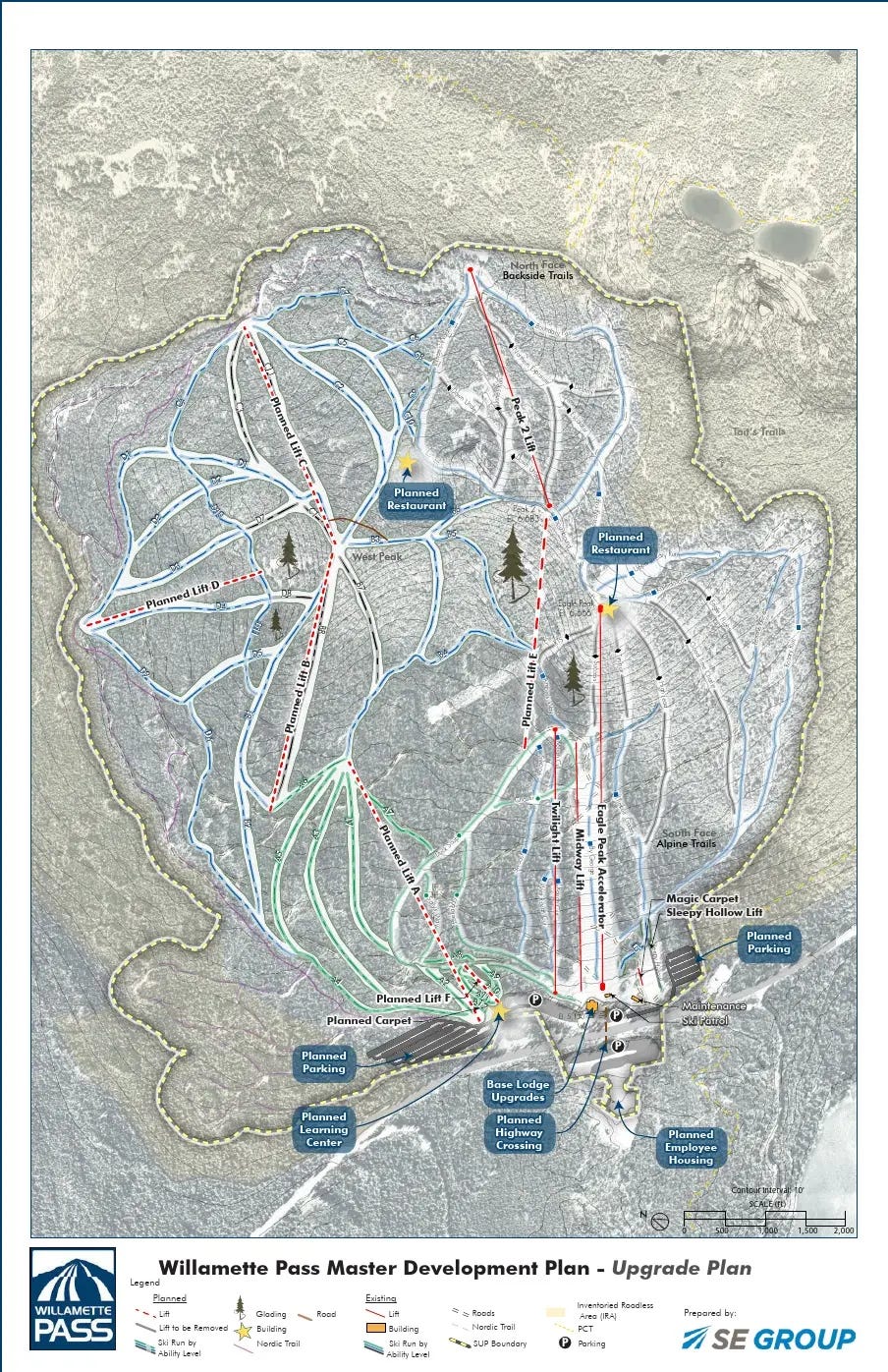

With the driveway swept and the hedges trimmed, MCP is ready for the real work: expanding the house. The mountain’s recently updated Forest Service masterplan would double the skiable acreage, add six new lifts, upgrade the baselodge, and throw in new parking lots, on-mountain restaurants, and on-site employee housing. Here’s the plan:

The type and capacity of the planned lifts is unclear as of now (While Forest Service masterplans are public documents, they can be nearly impossible to locate on their byzantine websites, other than within a few well-organized divisions such as Colorado’s White River National Forest; I’ve requested a copy of this document from MCP and will update this article with lift details if I receive it). And the notion of expanding the ski area is hardly new. Willamette Pass has teased some version of these trails, which would cover adjacent West Peak, on its trailmap for years:

But MCP’s version is more specific, expansive, and compelling. And it’s backed by this very important qualifier: this is a company that knows how to accomplish big things. They purchased and are about to combine two South American ski areas; improbably transformed long-overlooked Nordic Valley, Utah into a legitimate player with a huge expansion; updated the broke-ass lift fleet at Arizona Snowbowl; and supercharged snowmaking all over the portfolio, among countless other projects.

That’s not to say that this expansion will be automatic or easy. Forest Service masterplans are basically a basket of ideas. Each proposed lift, trail, and structure is subject to extensive public comment periods and environmental and regulatory approvals. And Willamette Pass straddles two national forests, the Willamette and Deschutes, potentially doubling the bureaucratic building pains. And even though the ski area is surrounded by thousands of square miles of raw forest, someone is likely to file 10 lawsuits arguing that the expansion would destroy woodpecker habitat or disrupt the flow of ancient beaver dams or traumatize the local pinecone population.

But MCP has worked with the Forest Service before. The company’s Sipapu, Sandia Peak, Arizona Snowbowl, Lee Canyon, Purgatory, and Brian Head ski areas all sit at least partially on Forest Service land. MCP has vastly improved all of them (with the exception of Sandia Peak, which MCP just acquired), in almost every way. This is the blueprint for what’s coming next in Oregon. No word yet on whether dairy-free cappuccino IPAs will be on tap in the cafeteria, but, from a skiing point of view, Willamette Pass is finally becoming a legitimate option for locals fed up with the volcano crowds.