The Only Problem with Claiming that Climate Change Is Killing Skiing Is That It Isn’t True

We’re trying too hard to simplify a complicated story

If you’re a regular here, I don’t have to tell you that lift-served skiing is doing just fine in America. The industry recorded 61.6 million skier visits last winter, the second-most ever and the sixth consecutive season – excluding the truncated 2019-20 campaign – to land among the nation’s all-time top 10. Operators have filtered those visits into investments, pumping more than $2 billion into lifts, snowmaking, lodges, employee housing, and other capital improvements in just the past three years. Examples of success abound, all over the map: Deer Valley in Utah is in the midst of the largest expansion in the history of North American skiing, Ober Mountain in Tennessee operated for 127 days last ski season, and formerly obscure and troubled ski areas such as Black Mountain in New Hampshire, Magic Mountain in Vermont, Holiday Mountain in New York, Hatley Pointe in North Carolina, and Norway Mountain in Michigan are thriving under persistent, energetic ownership groups. Multimountain ski passes have become so ubiquitous and popular that they have effectively reversed the business-consumer relationship that defined the industry for decades, as ski area operators who once competed to pull in the most skiers now focus primarily on controlling volume and maintaining a quality experience among a participant surge.

Lift-served skiing is not a dying industry or even a troubled one. These facts, however, appear to be powerless in the maw of a non-ski media that is determined to prove that climate change is killing skiing.

The latest example is an article from mountain bike-focused website Singletracks that examines the trend of mountain bike trail development at abandoned ski areas. The premise is interesting, and this is the first attempt I’ve seen to loosely collect such conversions, highlighting Sugar Loaf, Michigan; Marshall Mountain, Montana; Scott’s Cobble, New York; Mt. Telemark, Wisconsin; and Highland, New Hampshire – the only one that still runs its chairlift for bikes. It’s good information on a well-regarded and established website.

The trouble is the article’s long digression into why America has lost more than 1,600 ski areas. Here, the site repeats a familiar set of alarmist talking points:

Five major factors have coalesced to make operating a small local ski resort difficult, if not impossible: climate change and snow reliability, the snowmaking imperative and infrastructure costs, the liability crisis and insurance costs, economic pressures and business model challenges, and regulatory and operational barriers. We recently covered the massive insurance liability risk affecting Oregon ski resorts, but the overall upward trend of insurance prices is nothing new — it’s been underway since the 1977 case of Sunday v. Stratton Corporation.

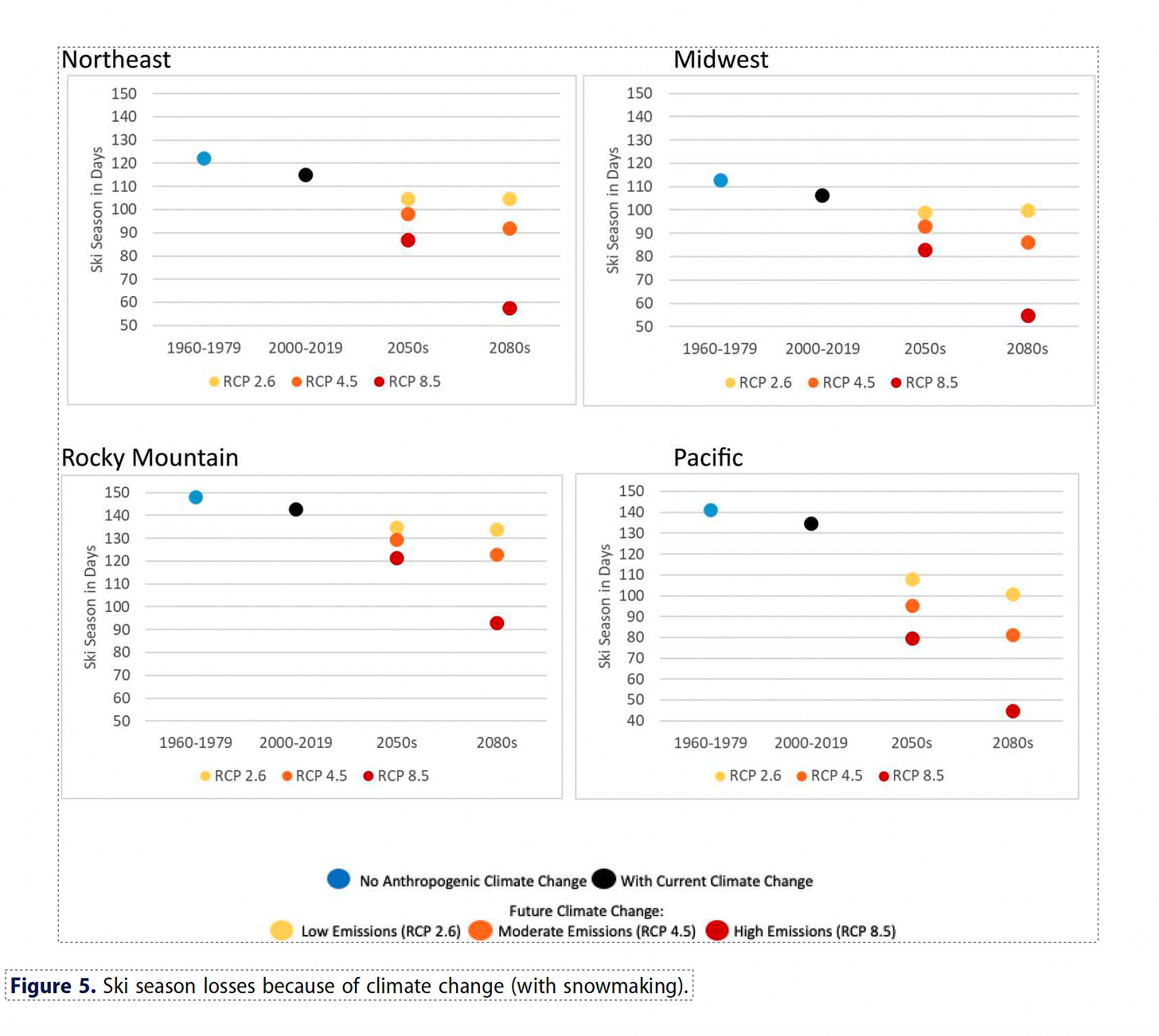

By far the biggest factor affecting these small ski resorts is climate change. Research examining more than 220 ski areas across four U.S. regional markets found that the average ski season has shortened by between 5.5 and 7.1 days during the 2000-2019 period compared to 1960-1979. And this trend is accelerating: projections suggest seasons will shorten by an additional 14-33 days by 2050 under various emissions scenarios, with some locations experiencing reductions of 27-62 days by that timeframe.

Climate change affects areas differently. While higher-elevation resorts in the Rockies and Sierras might only face shortened, inconsistent seasons (which still cost the U.S. ski industry an average of $252 million per year), the results for low-elevation ski resorts in the Midwest and Northeast are catastrophic. This is precisely why these regions have seen the most ski resort closures over the years.

None of this will sound terribly wrong to a casual reader. And on the surface, this equation adds up: LOTS OF SKI AREAS IN THE PAST + CLIMATE CHANGE = FEWER SKI AREAS TODAY. But it’s wrong: American skiing in the 2020s offers more and better-quality skiing to more skiers than at any time in the nation’s history. To understand this counterintuitive reality, let’s dissect the Singletracks article:

Most U.S. ski areas are still small and independent

Five major factors have coalesced to make operating a small local ski resort difficult, if not impossible:

It is difficult to operate a small local ski area. But it’s not impossible. In fact, most U.S. ski areas are still small, local, and – while this isn’t stated explicitly – independent.

First: small. Well, small is hard to define, but the simplest metric is skiable acres, and all 44 ski areas in Michigan combined are roughly the size of Vail Mountain, Colorado; ditto for all 50 active ski areas in New York. We can also define “small” by infrastructure, and this is a telling stat: just 139 of 509 active ski areas (27 percent) spin at least one detachable chairlift. And 115 U.S. ski areas (23 percent) run only surface lifts. Most U.S. ski areas are still small compared to the top 50 or so destination resorts.

Second: local. “Local” is a loaded word, typically used by skiers as a stand-in for “independent.” After all, Paoli Peaks, Indiana, is a hyperlocal ski area that draws skiers mostly from its immediate drive radius. But it’s owned by Vail Resorts, the largest ski area operator on the planet. Taos, Jackson Hole, and Alta – all major destinations – are independent (though ownership is often a complex network of stakeholders or funneled through a larger company). The easiest way to measure the status of America’s ski area ownership matrix is this: 151 (30 percent) of U.S. ski areas are operated by an entity that runs two or more mountains, meaning 358 (70 percent), are independently owned and operated.

Most ski areas failed when they became obsolete

… climate change and snow reliability, the snowmaking imperative and infrastructure costs, the liability crisis and insurance costs, economic pressures and business model challenges, and regulatory and operational barriers. We recently covered the massive insurance liability risk affecting Oregon ski resorts, but the overall upward trend of insurance prices is nothing new — it’s been underway since the 1977 case of Sunday v. Stratton Corporation.

This is mostly correct, though perhaps overly broad. I suppose chairlift affordability, labor costs, and utility rates could fit under “economic pressure and business model” or “regulatory and operational barriers.” But, yeah, I just wrote a story about the contribution of escalating insurance costs to the closure of tiny Four Seasons ski area in New York after 63 years. But – and this was the focus of the story – Four Seasons was not a victim, but an outlier, whose decades-long existence was more a testament to the efficacy of the dying ski-area-owner-as-hands-on-artisan/curator/hotelier model than an indictment of the insurance industry’s relationship to ski areas. But here’s the most important line in the article:

By far the biggest factor affecting these small ski resorts is climate change.

This is not accurate. The biggest factor affecting small ski areas is that they often have to compete against large ski areas. Let’s jump to the end of the Singletracks article, with the anecdote that inspired this ski-areas-to-bike-trails story:

I rode some ripping singletrack through an area known as Scott’s Cobble. I wouldn’t have realized that it was a defunct ski area unless my local guide had pointed out an old rope tow tower hidden in the dense undergrowth. The verdant Northeast forest was so thick that I could barely tell a ski run had even existed before! Once you knew what to look for, it was obvious, but without the tip, I would have just blown through without a thought.

Sure, it’s a bummer to lose a ski area. But context is important. Scott’s Cobble is one of 14 now-defunct ski areas orbiting Lake Placid, New York, two-time host of the Winter Olympics. In Lost Ski Areas of the Northern Adirondacks, Jeremy K. Davis, who also runs the New England Lost Ski Areas site, spells out the fate of this once-busy ski area, a 300-ish-footer that served the town of North Elba from 1938 to 1973:

In 1955, after nearly twenty years of being a rope-tow ski area, the Town of North Elba appropriated $15,000 (nearly $130,000 in 2014 dollars) to replace the lifts with a more modern Pomalift. … Skiers welcomed the improvement, which helped Scott’s Cobble become a modern ski area.

Just a few years later, nearby Whiteface would open, a ski area with tremendous vertical and terrain – especially compared to a smaller area like Scott’s Cobble, despite its recent upgrades. There was discussion that the area should be shut down and that its usefulness was over. Ronald MacKenzie, who had been part of the board of the Lake Placid Ski Club that had urged Scott’s Cobble to open in the first place, pleaded with the town to keep the ski area in 1960, stating that it still had a purpose as a training and learning hill. His pleas were heard, and the area remained open. …

The draw of Whiteface and other larger mountains continued to drain Scott’s Cobble of potential skiers. Its limited terrain and vertical could not compete with the larger developments. The area consistently lost money, nearly $4,000 a year through 1973. This loss cold not be sustained, and the town decided that the time for downhill skiing at Scott’s Cobble was over.

And that’s it. Cars mostly replaced horses for transit. The internet mostly replaced paper mail for paying bills. Credit cards mostly replaced cash for everyday transactions. And fewer, but larger, ski areas mostly replaced a glut of smaller ski areas for the skiing public. Scott’s Cobble, and all of the other tiny-tot ski areas in its vicinity, did not close because winter stopped happening in Lake Placid. They closed because Whiteface Mountain, whose 3,166-foot vertical drop is the tallest in the East and whose Slides terrain is the most extreme inbounds zone in the East and whose Cloudsplitter Gondola is the longest ski lift in New York and the third-longest in the East, opened in 1958 and gradually dominated the local skiing public’s attention. And also because Whiteface is owned, operated, and subsidized by New York State, an arrangement that is the source of bitter resentment among the taxpaying independent ski area operators that must compete directly with Whiteface and its sister mountains Gore and Belleayre.

Today, the closest beginner area to Whiteface – which itself has developed one of the most complete beginner centers in U.S. skiing, remaking its substantial green pods with three new chairlifts since 2020 – is Mount Pisgah, owned by the village of Saranac Lake, 40 minutes away.

This is not to say that the inevitable trend in skiing is toward fewer, larger ski areas, or that no-frills beginner hills have no role in the ski ecosystem. In our cultural enthusiasm for bigger, we probably, collectively, prematurely closed too many small ski centers that would be ideal for kids programs and the thousand-laps terrain-parks model that has been so crucial to Midwest skiing’s survival. And, in fact, we are seeing a slow resurgence of these dormant hills. Snowland, Utah and Nutt Hill, Wisconsin re-opened with lift service this winter after decades dormant. And Cuchara, Colorado, spun its 266-vertical-foot Chair 4 this winter after sitting idle since 2000.

Why didn’t Napoleon just scramble the jets?

A lot of Singletracks’ climate-change-is-killing-skiing analysis relies on the misreading of an academic paper:

Research examining more than 220 ski areas across four U.S. regional markets found that the average ski season has shortened by between 5.5 and 7.1 days during the 2000-2019 period compared to 1960-1979.

This is not what the research says. This particular paper used a computer simulation to estimate that the average ski season from 2000 to 2019 was shorter than what they may have been had no climate change happened relative to hypothetical ski seasons from 1960 to 1979, if ski resorts had deployed 2000s snowmaking technology in that era. If that’s confusing, this is the exact language used in the study:

Relative to 1960–1979, modelled average ski seasons (with snowmaking) in the 2000–2019 period have shortened between 5.5 and 7.1 days.

But we do have snowmaking, a fact that the study’s authors acknowledge and explicitly say has lengthened American ski seasons:

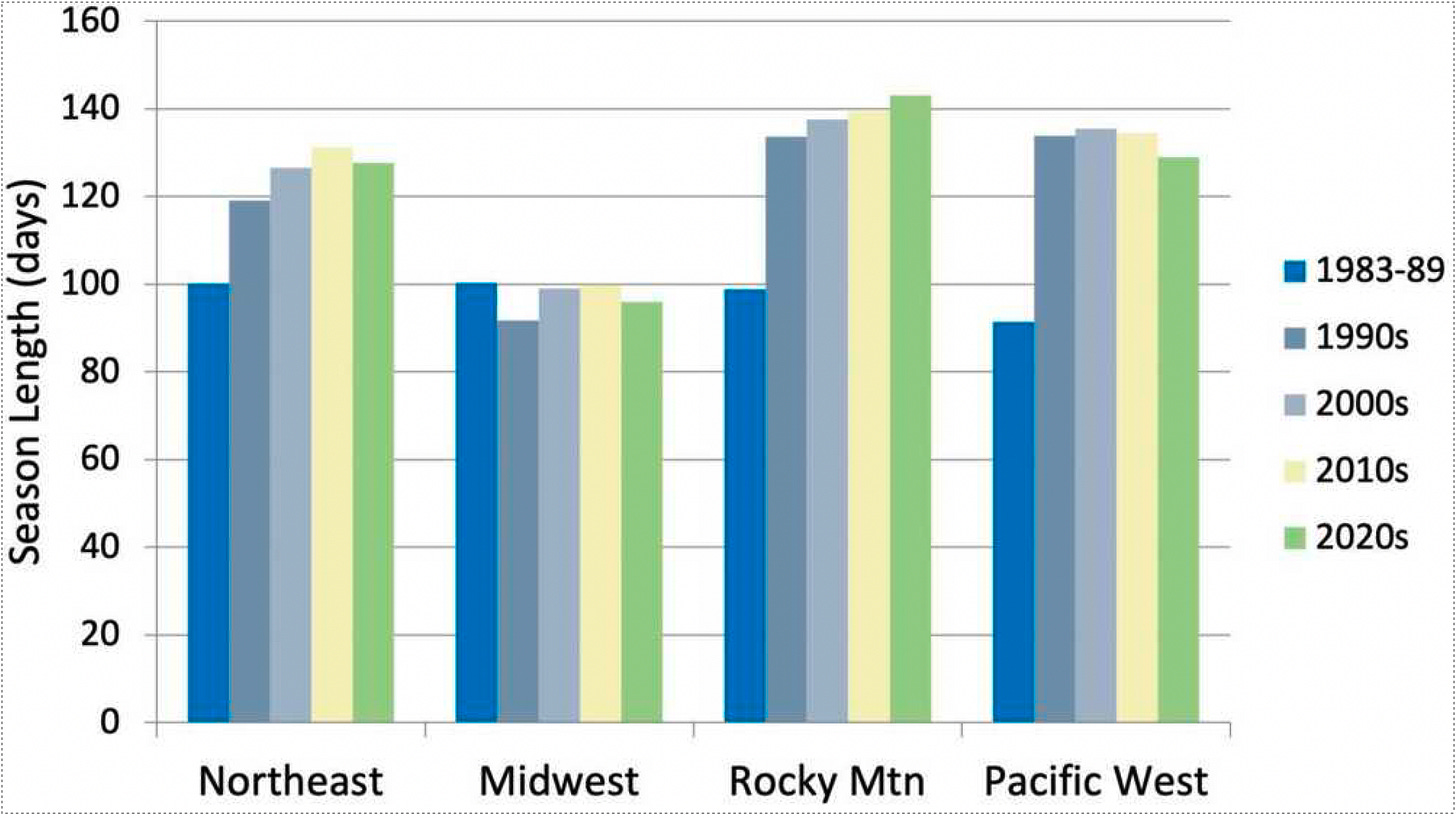

The massive investment in snowmaking enabled US regional ski markets to increase the average ski season length from the 1980s to 1990s (except the Midwest) and again from the 1990s to 2000s (Figure 4), even as temperatures increased and an average length of annual snow cover began to decline (Climate Central, 2022a, 2022b; Siirila-Woodburn et al., 2021). Only in the 2010s and early 2020s have average ski seasons stabilised or declined slightly (except for the Rocky Mountains), indicating that the adaptive capacity of snowmaking is no longer able to completely offset ongoing climate changes and that the era of peak ski seasons has likely passed in most US markets.

So average ski season length is up substantially since the 1980s in all regions other than the Midwest – an expected outcome of widespread advances in and deployment of snowmaking.

Again, the study does not use these actual season lengths, which were substantially shorter, in general, than the hypothetical numbers they produced. These fake seasons are indicated in the chart below (extracted from the study), with blue dots, which show how long an average ski season may have been had we applied modern snowmaking technology to 1960-to-1979 weather data:

But that is a strange way to measure ski seasons – why not just examine actual ski area open and close dates from each era? Many ski areas did not have snowmaking systems for all or part of that 1960-to-1979 period – and the snowmaking systems they did have made far less snow using far more energy than today’s hyper-efficient guns. This is like asking what the American Revolution would have looked like had Britain possessed F15s and helicopters. Probably not good for America. But who cares? That didn’t happen.

The number of ski areas matters less than we want it to

Singletracks, like so many other sources, leans too heavily on the raw number of ski resorts, presenting a Bubonic Plague-style tally of our ravaged ski regions:

In the Northeast, at least 670 ski resort closures have been documented by websites like the New England Lost Ski Areas Project, with another 31 closures documented in the Mid-Atlantic by DCSki. The Midwest has seen about 483 ski areas close over the years, according to the Midwest Lost Ski Areas Project. While many resorts have closed across the Western USA, the Midwest and Northeast have been disproportionately affected. Western states like Colorado have lost ~137 ski areas, while California has lost 134, 48 in Washington, 72 in Idaho, over 57 in Oregon, 12 in Utah, 10 in Wyoming, 10 in Nevada, and even more in states like Arizona, New Mexico, Montana, North Carolina, etc.

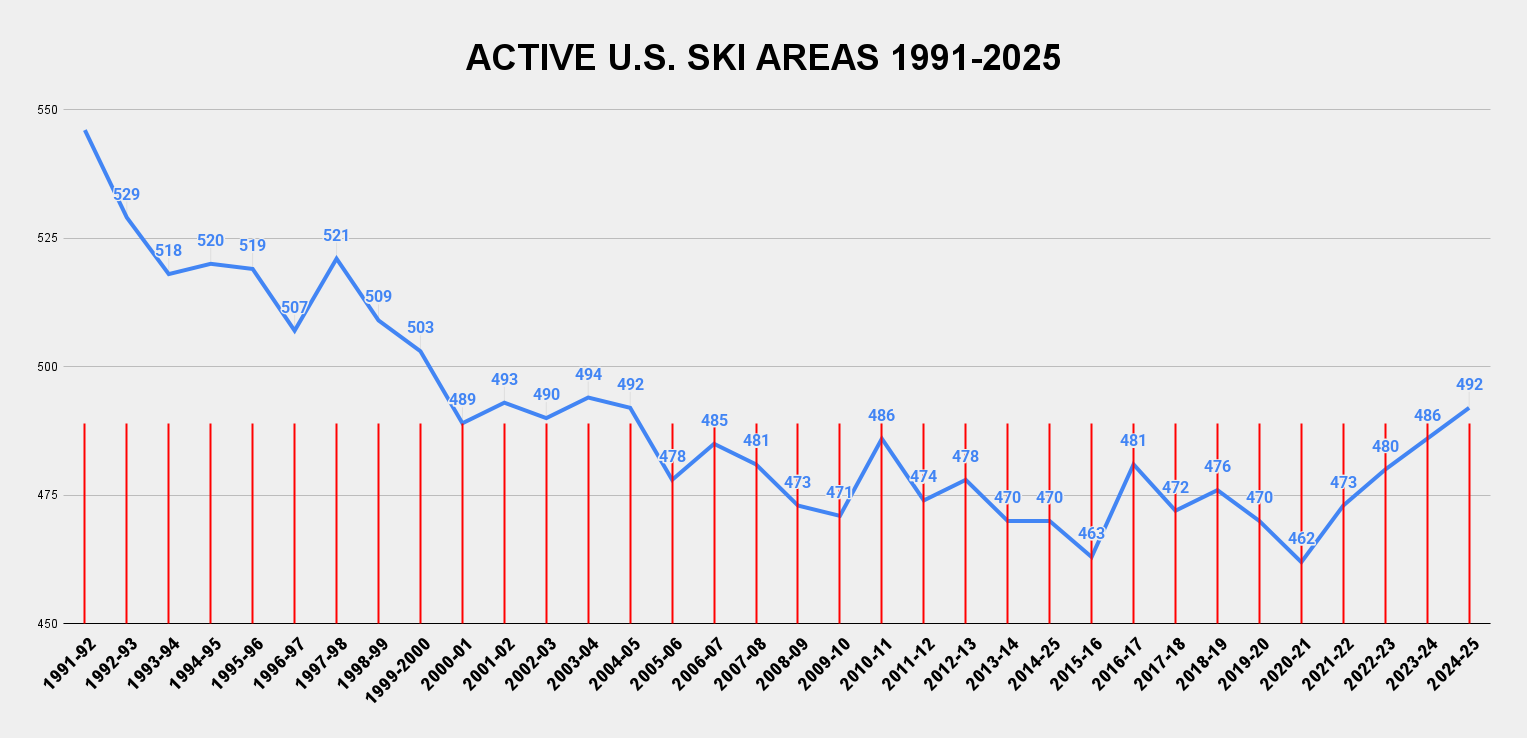

For those keeping track, that’s at least 1,664 ski resort closures — much higher than the ~513 drop from peak operation to today. Note that the 513 number is a net loss nationwide. As some resorts have closed, others have opened — but the overall trend has been toward fewer ski areas, and it doesn’t look like it will let up anytime soon.

It actually does look as though it will let up… about 25 years ago. After rapid declines in the 1980s and ‘90s, the number of active U.S. ski areas stabilized around 2000, and has climbed for the past four winters (the 2020-21 stat reflects the decisions of several small community ski areas to sit out that season and its complicated health-and-safety regimen):

There’s a lot more skiing than there used to be

I want to go, now, to the top of the Singletracks article, to make a larger point about ski terrain and operations:

Across the USA, rusting lift poles stand forlornly above abandoned ski slopes that haven’t heard the laugh of a child in decades. These decrepit lifts and open clearings through dense woodlands are slowly being reclaimed by the dense forest overgrowth until eventually, they disappear entirely.

It’s hard to imagine now, but in the 1960s, approximately 1,000 different ski areas operated across the United States. Today, that number has been cut in half, with roughly 487 resorts still operating. But those numbers don’t even tell the whole story.

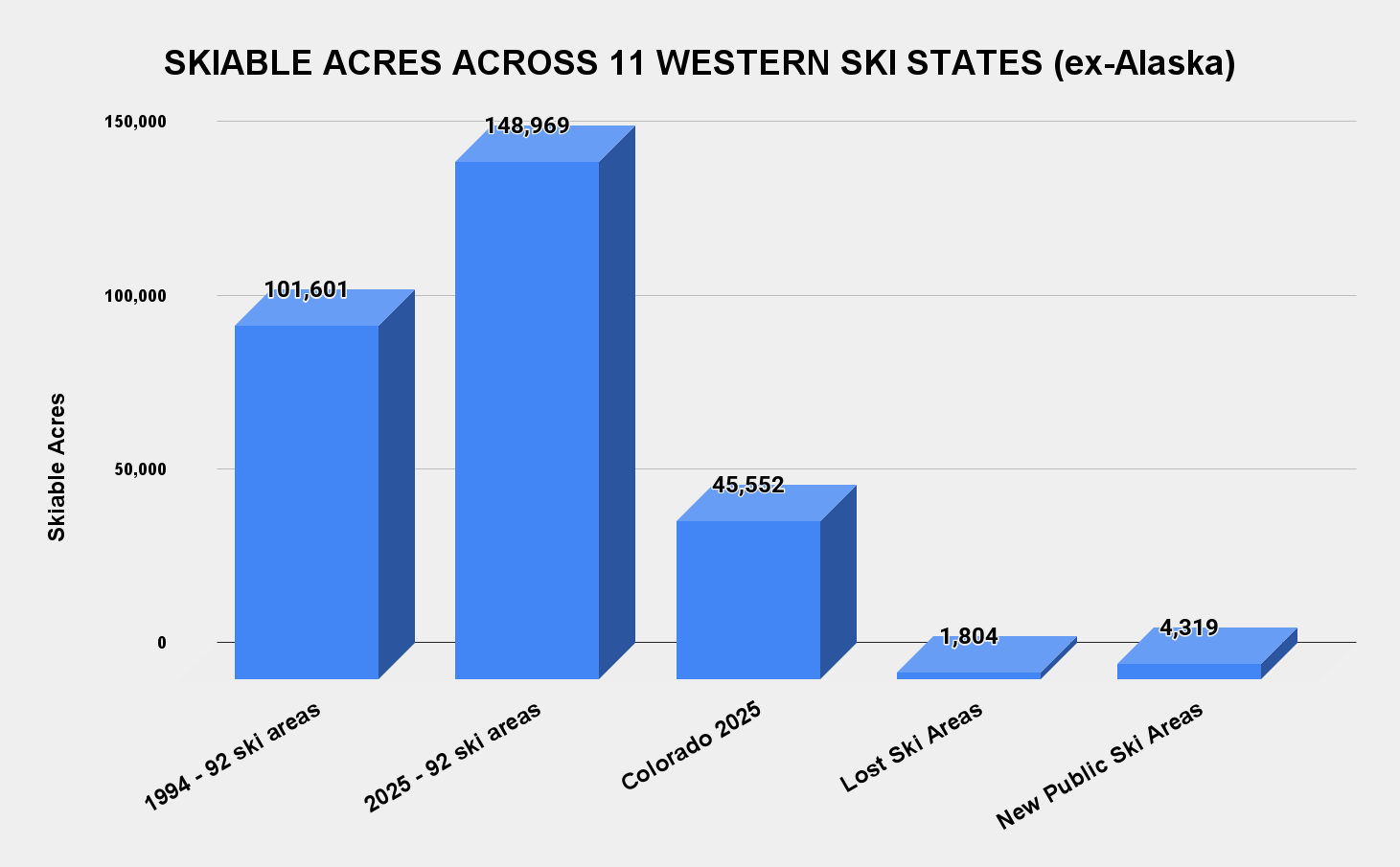

That’s true. Those numbers don’t tell the full story, because the full story is this: while fewer ski areas operate today than in the past, the total amount of skiable terrain is far larger now than it has ever been. As I documented last year, U.S. ski areas have added more than 54,000 skiable acres since the early 1990s - more ski terrain than exists in modern Colorado, our largest ski state by acreage:

These numbers account for closed ski areas, and only include the 11 contiguous western U.S. ski states. But what we see here is a fairly typical capitalist business arc: an initial surge of entrepreneurs competing for market share in an industry poised to explode, usually because of technological advancements (aided by a loose nascent regulatory structure around those technologies) that accelerated mass production and eased the experience for common consumers, followed by long-term consolidation and overall participant growth as the best business operators succeeded, pushing out the less skilled. Specifically, for skiing: a post-World War II surge in technology (mass production of chairlifts, snowmaking, metal-edged skis and plastic boots) and disposable income inspired hundreds of ski area builds in a low-regulation environment in which the federal government was actively pushing for recreational leases of public lands, especially in the West. At first, lift-served skiing would have been a low-expectation product for a low-knowledge consumer: skiing was new for almost everyone. But as some ski areas upgraded and others did not, consumers made their preferences clear, steering their dollars and attention to the highest quality experience. So today we have fewer, better ski areas offering more overall skiable terrain than we ever have.

Consider an analogy: some 3,000 auto manufacturers have existed in America. Then for a long time we had three: Ford, GM, and Chrysler. Only with the advent of better electric vehicles have we seen this number tick back upward in the past decade, then decline as companies like Nikola and Workhorse sputtered. But no one is going around saying that the auto industry is dying because a bunch of garage-band outfits failed to outcompete Ford in 1908. In 1985, The Los Angeles Times ran an article comparing the then-upstart personal computer industry to the by-then-long-established auto industry:

About 3,000 auto companies, many of them in people’s garages, have started and failed in this country. Now, we’re down to four U.S.-based car manufacturers. Meanwhile, we have about 500 computer companies and 4,000 software outfits, many of them still in people’s garages. A few years hence, everyone says, we’ll be down to a handful of computer makers.

One reason so many people leaped into these industries is that they thought Americans would buy every car and computer that was cranked out. People were buying so many cars in the 1920s that the auto moguls geared up for imminent sales of 6 million cars a year. Alas, that level wasn’t reached until 1955, and car producers by the hundreds fell by the wayside.

In other words, once a “car” wasn’t just a bicycle seat and a steering wheel steel-bolted to an exposed engine, consumers supported the makers of the most reliable and comfortable machines; just as once a “ski area” wasn’t 50 feet of vert served by a dogsled and an outhouse, skiers gravitated toward the ones with chairlifts, baselodges, and trail variety.

A planned decline

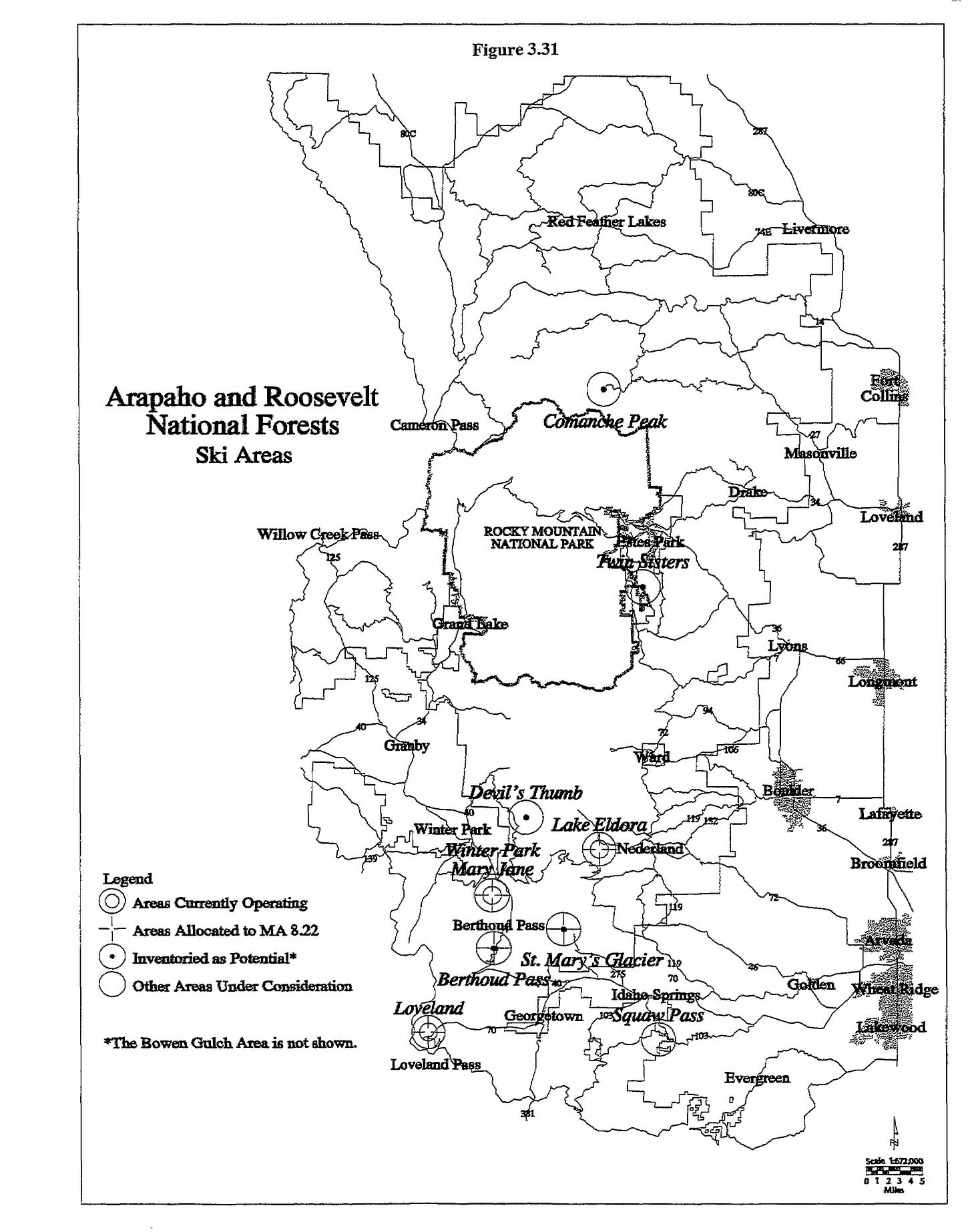

Archival documents suggest that the industry was more self-aware than we may now appreciate, and that the shrinkage in the number of ski areas was not only anticipated, but planned for. Check out this passage from a circa 1993 Arapaho and Rossevelt National Forest (ARNF) report:

Predictions are that the rapid growth of the ski industry in the 1970s and 1980s has ended and that in the next decade skier demand will be met through expansions at existing areas, with few new ski resort communities being established.

Not only did the report expect few new ski areas, it framed the closure of existing facilities as probably essential for the industry’s health:

A trend evident in Colorado is that larger ski areas tend to succeed and expand while smaller, marginal areas struggle to stay in business and many fail. Since 1982, 224 small ski areas (nationwide) have been forced to close due to an inability to compete with larger ski areas.

The imperative for reframing skiing for a modern era seemed to be the National Forest Ski Area Permit Act of 1986, which sought to modernize and standardize the ski area permitting process that had originally been authorized in 1915 and had not been updated since 1956. The priority: refocus on operating fewer, larger ski areas in the best and most accessible locations over making sure everyone lived near a ski area.

The report points, for example, to the by-then-defunct St. Marys Glacier ski area, which recorded reliable snowfall but suffered from “antiquated lifts, a small parking lot and deteriorated facilities currently located on private land [that] are obsolete by today’s standards.” Further, the ski area’s nasty access road, milquetoast terrain, and high sewage treatment costs put it at a disadvantage to all of those huge ski areas sitting right off Interstate 70.

ARNF, then, favored expansion of its Loveland, Eldora, and Winter Park ski areas, which, at the time, could collectively increase their skier capacity by 75 percent “by completing expansions that are currently in master development plans.” Winter Park alone could expand capacity by a stunning 851,200 skiers per winter, while Loveland could handle another 524,400. Officials already had proof that redirecting skiers toward better ski areas worked: rapidly modernizing Eldora and Loveland, the report noted, “grew signicantly” following the closures of nearby Berthoud Pass, Ski Broadmoor, and Ski Estes Park.

In conclusion: go skiing

Lift-served skiing is not dying. It is evolving. Climate change is part of that story, but only part, and one that has mostly been solved by ever-more-advanced snowmaking technology (yes, an energy-and-resource-intensive process, but one that typically borrows, rather than uses, water that melts back into the watershed at winter’s end; and like any business in an industrialized economy, skiing is connected to the grid). If the climate change calculus changes, so will my analysis. For now, I’ll just leave you with what I wrote in October under the header “what are lift-served skiing’s actual problems”:

Skiing - weather-dependent, mostly rural, universally recognized but niche in practice, expensive if you need it to be - is especially vulnerable to distorted, inflated, or imaginary problems.

Consider, for instance, the reductive narratives around climate change, a favorite come-to-a-conclusion-and-seek-supporting facts headline of the non-ski media. Superficial statistics support the assumption that our warming planet is increasingly hostile to snow-based recreation: the 1980 White Book of Ski Areas itemizes 630 active U.S. ski mountains. My best-case-scenario count for the 2025-26 ski season is 509. Well that’s not good. But we must consider additional facts: U.S. ski areas hosted 61.6 million skier visits last winter, the second-most on record and 21.9 million more than the 1980-81 ski season; the snowiest winter in the recorded history of the American West was 2022-23; and as the number of ski areas has decreased over the decades, aggregate ski terrain has increased by more than 20 percent, with expansions and new ski areas adding more than 54,000 acres of terrain since 1994 (even when accounting for resort closures).

So what’s going on here? Is this a dying industry or a thriving one? By asking questions rather than working backward from conclusions, we reveal a complicated narrative. Lift-served skiing exists within a set of complex systems, natural and manmade, each presenting challenges of varying difficulty. Unpredictable snowfall, it turns out, has a relatively simple, if expensive, solution: snowmaking. But manmade systems – bureaucratic, regulatory, activist, legal – have evolved more radically than the natural, and these are often more difficult to manage. The ski area operators I speak with daily worry about the escalating costs of liability insurance, labor, utilities, and infrastructure such as new chairlifts and buildings; expensive and protracted legal battles over even the simplest upgrades; adapting an analogue business to a digital world; building viable offseason revenue streams; and holding the real-world attention of a populace en thrall to their Pet Rectangles. Operators do worry about climate change, but those concerns, in the near-term, are mostly focused on the drier months – Sierra-at-Tahoe did not lose its 2021-22 ski season due to too little snow, but to too much wildfire.

Similar nuances exist around the narratives of skiing’s affordability, diversity, and consolidation: never as bad as we assume, complicated in ways that are hard to appreciate without deep analysis.

Great article (as always). I am reminded of my favorite lesson learned in Statistics - "Correlation is not causation." Climate change is an issue for the industry but claims of it's demise are greatly overstated!

re: your comment about snow returning to the watershed. Biosphere 2 is currently researching where water ends up when it rains on a mountain slope. They have sensors embeded all around an artificial slope in a closed system to find out how much seeps in versus runs off or evaporates. This could give interesting insight into how snow water stays in the area or not at ski areas. Keep a lookout for what they find (although it may be years out).