Rob Katz Returns As Vail Resorts CEO – 8 Changes to Make Now

The Epic Pass changed skiing, but then skiing blew right past the Epic Pass - how Vail can catch up, fast.

Vail Resorts named Rob Katz CEO on Feb. 28, 2006. Over the next 15 years, he would transform the company and, in the process, the entire American ski industry’s business model. Under Katz, Vail introduced the Epic Pass and exploded from a five-mountain, regional operator into a 37-resort monster with outposts across North America and Australia. Epic Pass sales surged every year following the product’s 2008 debut, often by double-digit percentages. For the 2021-22 campaign, which Katz led for most of the March-to-December Epic Pass sales period, Vail sold 2.1 million Epic Passes and clocked 17.3 million skier visits. Finance Bro took note: the company’s stock price skyrocketed from $33.04 in February 2006 to $354.76 the day his successor, Kirsten Lynch, stepped into the CEO role on Nov. 1, 2021.

In the 1,303 days until Lynch resigned and Vail re-named Katz CEO on May 27, the company continued to change and, by many metrics, grow. Vail’s Epic Day Pass evolved into a best-in-the-industry, six-tiered, build-your-own-pass product. Vail established an owned footprint in Europe, purchasing two well-known Swiss ski resorts. Employee retention improved following a minimum-wage boost to $20 per hour and other benefits. Vail aggressively modernized the skier experience, moving Epic Passes onto smartphones, consolidating resort-specific information onto the My Epic app, and rolling out a seasonlong gear rental program. The company also adopted a softer competitive tone, a departure from the bar-brawling Katz era, during which Vail, among other cowboy adventures, mounted a hostile takeover of Park City and skunked Colorado’s ski area trade organization.

But Epic Pass sales stagnated under Lynch, then declined. Following a 20 percent 2021 price cut (under Katz), that lead to a nearly 50 percent increase in units sold, pass unit sales inched up just six and four percent over the following two seasons, before declining for the first time ever leading up to the 2024-25 winter. The stock price never crashed, but it slumped, standing at $151.50 on the last day of Lynch’s tenure (it closed at $156.01 today). Owned-resort skier visits fell following the poor 2023-24 winter, but are on track to decline an additional three percent for a 2024-25 ski season in which the National Ski Areas Association reported a 1.6 percent nationwide skier visit increase and America’s second-best ski season ever.

A cast of bad guys could take credit for this declining interest in the Epic Pass and Vail’s ski areas: high-profile community revolts in Vail and Park City, walk-up lift ticket prices that would embarrass a luxury handbag store, a disastrous Christmas week Ski Patrol strike at the company’s largest U.S. ski area, and a general sense – garnered from persistent negative on-the-snow field reports, perceptions of deferred maintenance, and sometimes comically short seasons at its regional ski areas – that Vail Resorts had begun to take its North American customers for granted.

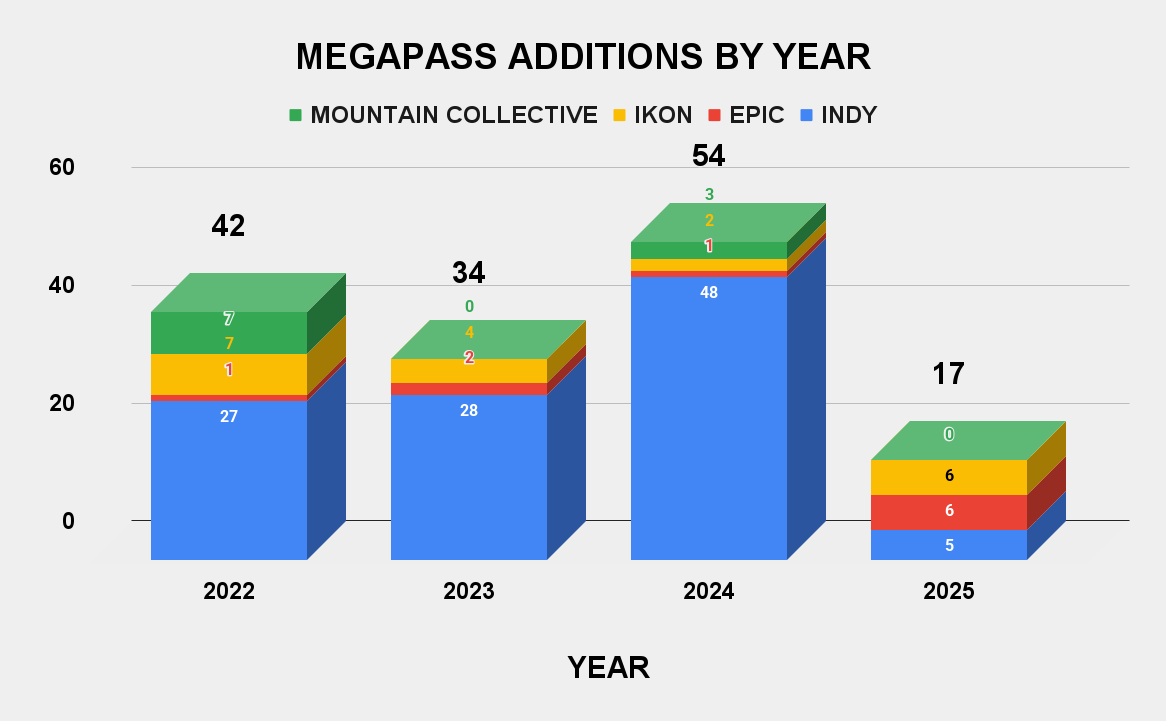

All of which may have been fine, had Vail not begun losing the pass innovation battle that it had so effectively spawned. Between 2022 and April 2025, the Ikon Pass added 19 new partners, Mountain Collective added 10, and Indy Pass added an astonishing 108. Vail lost three (the two Sun Valley mountains and Snowbasin), and added just four, all outside of North America. Ikon and Indy constantly tweaked access tiers and blackout dates, while Vail maintained far more generous holiday access at even its busiest ski areas, leading to widespread overcrowding on peak days. The Epic Pass network, large as it was, began to feel crowded into too few geographies, with an insufficient number of true destinations to accommodate an ever-growing number of passholders.

Whether Katz can re-invigorate Vail Resorts in the same way that he transformed the company into American skiing’s most prominent entity remains to be seen. The ski market that Vail disrupted has caught up with and surpassed the onetime disruptor. The playbook for Katz 2.0 will have to differ from the 2006-2021 era: few obvious growth pathways remain, Vail’s brand equity has lost much of its glimmer, and the revenue that multi-mountain pass membership generates for large independents has reduced their incentives to sell to a larger operator. It remains unclear whether skiing actually is – or ever can be – a growth industry, or if Vail’s head start helped artificially drive visitation and pass sales numbers by consistently stacking new local passholder bases onto one balance sheet.

But Vail can take many obvious and immediate steps to arrest, and ultimately reverse, the declines in pass sales, skier visit numbers, and stock price. Here are eight:

1) Make Vail the best everywhere

Here’s a hopeful 2017 snippet clipped from Inside Hook, going into Vail Resort’s first season as owner of humble Wilmot Mountain, 200 vertical feet of Wisconsin glacial dump clipping the Illinois border. The section header captures the predominant ski industry anxiety and expectation of the era (boldface text below mine).

“Vail standards, Midwest setting.”

Growing up in the Chicago suburbs, [then-Wilmot GM Taylor] Ogilvie spent his winters at Wilmot. What he remembers are the “old clanky chairlifts” and eating in the car because the lodge was too crowded for his family to sit. The millions that went into this project paid for three new high-speed, four-person chairlifts [this is untrue; the quads are fixed-grip machines], a reconfiguration of the lodge to accommodate 400 more seats and Colorado-grade snowmaking [this is a little backwards; “Colorado-grade” snowmaking tends to be of the just-enough variety; more impressive would be a Colorado ski area with “Midwest-grade” snowmaking]. And if you need some real mountains, you can pick up Vail’s Epic pass, which gets access to Wilmot as well as Vail, Beaver Creek, Heavenly, British Columbia’s Whistler Blackcomb and even resorts in Austria, France, Italy and Switzerland.

This is what we all hoped for, right? These master ski area operators stomping into the hokey-doke hinterlands and showing these Midwestern yucksters how to run a ski area.

Instead, as Vail has stacked Midwest resorts, these longtime community ski staples have too often delivered shortened seasons, inconsistent schedules, ever-fluxuating leadership, and reduced operating days and hours. Paoli Peaks, Indiana operated for 22 days during the 2022-23 ski season. The state’s other ski area, Independently owned Perfect North, operated 86 days that same winter. That’s in part because Perfect North has so optimized its snowmaking system that it can punch all 245 of its snowguns on at once, burying its 100 acres in less than two days. Check out the absolute blast furnace burying the bump on Jan. 4, 2024 (click for video):

And here’s Vail’s entry the next day: 65-acre Paoli Peaks updating followers that “the team started [snowmaking] from the bottom and will continue to work our way across the resort.”

Everyone who works for Vail should be embarrassed by this. You are Vail. Possessor of: resources, institutional knowledge, entire metropolitan markets, data, an amazing passport to the hither and yon. No skier will ever be happy with everything, and there is nothing that will make every skier happy. But if a family that opened a ski area on a lark in 1980 can run 86-day ski seasons in Indiana, then the self-proclaimed agent of the Experience of a Lifetime damn well better figure out how to do the same thing – and better.

I have no direct evidence of this, but I suspect that part of the story behind Epic Pass unit-sales drops is Vail Resorts’ lack of respect for its Midwest and Mid-Atlantic feeders. Somewhere between 2016 and 2020, “Vail standards, Midwest setting” became “the rubes have no choice, to hell with their dumb little speedbumps.” The leadership shuffle is constant (more on this below), snowmaking feels constrained (Vail officials insist it is not; locals consistently tell me otherwise), and seasons are often shorter than those of nearby competitors. “Vail bought my local” has become a complaint, where it should be harbinger of something great, like Oklahoma City improbably landing an NBA team.

End this. Treat every mountain as though it were Vail Mountain. Treat every opening day as though it were Keystone vs. A-Basin in October. Make sure people in Columbus are saying, “well, Mad River is only 300 feet tall, but Vail installed this snowmaking system that makes the firebombing of Dresden look like the candle array on a one-year-old’s birthday cake.” To prove how bad you want the crown, wage friendly battles of the sort that corporate-owned Boyne Mountain does each May with uber-indie Mount Bohemia - first to close donates $1,000 to the charity of the winner’s choice. Run a four-month ski season in Missouri and make sure everybody knows how hard that is.

I skied powder at A-Basin on May 7 with 100 percent of the lifts spinning. Down the road, Breck was open, but with only five lifts live and a small percentage of their acreage available. The rest of Vail’s Colorado mountains were long-closed. Why?

South-facing Black Mountain, New Hampshire closed with top-to-bottom skiing on May 3 this year. Thirteen miles away, north-facing, higher-elevation Wildcat, which under previous ownership had rarely closed before the third weekend in April, had already been shuttered for nearly a month. Why?

Every single year, several Alterra-, Boyne-, Powdr-, and MCP-owned ski areas push their seasons into May and June. Vail gives us a half-May of Breck and the top of Blackcomb. Why?

Go kick ass. You’re Vail. The America of ski companies. But like America, Vail used to win wars. Now they just go “dang it” and leave.

2) Bring in the pass whisperers

Since removing Jackson Hole and Aspen’s four mountains from the Ikon Base Pass in 2020, Alterra has made more than two dozen alterations to Ikon Pass access. Sometimes they throw the gates open, as when Stratton and Sugarbush moved from five days to unlimited on Ikon Base or when A-Basin ditched holiday Base pass blackouts. Other times, Alterra moves in a more restrictive direction, shifting Crystal from unlimited on Base to five days with blackouts, or moving Alta and Deer Valley off Base. Every time, the formula appears to be the same: track pass usage and impact on a specific ski area, then adjust access to reverse negative impacts on the skier experience.