Who

Bill Cairns, President and General Manager of Bromley Mountain Resort, Vermont

Recorded on

October 24, 2022

About Bromley

Click here for a mountain stats overview

Owned by: Joseph O'Donnell

Operated by: The Fairbank Group

Pass affiliations: None

Reciprocal pass partners: 1 day each at Jiminy Peak, Cranmore

Located in: Peru, Vermont

Closest neighboring ski areas: Magic Mountain (14 minutes), Stratton (19 minutes)

Base elevation: 1,950 feet

Summit elevation: 3,284 feet

Vertical drop: 1,334 feet

Skiable Acres: 300

Average annual snowfall: 145 inches

Trail count: 47 (31% black, 37% intermediate, 32% beginner)

Lift count: 9 (1 high-speed quad, 1 fixed-grip quad, 4 doubles, 1 T-bar, 2 carpets - view Lift Blog’s of inventory of Bromley’s lift fleet)

Uphill capacity: 10,806 skiers per hour

Why I interviewed him

Vermont is one of those states where you can see a lot of ski areas from the tops of other ski areas. I find this thrilling. I love all ski areas. Relish them. That such machines, so similar yet so distinct, could be so concentrated sparks within me some thrill of exotic immersion, of adventuring into zones dense and wild and compelling.

Of these peak-to-peak views, none is more dramatic than south-facing Bromley viewed from north-facing Stratton. In Vermont, which manages sprawl better than the rest of U.S. America, your view is most often of mountains, the endless Greens, treed and rippling toward Canada, radio towers blinking against the sky. But Bromley, etched magnificently into the expanse, owns the view from its larger neighbor.

Bromley and Stratton are two points of Southern Vermont’s so-called Golden Triangle. The third is Magic. The three ski areas have a weird joint history. Of owning and buying and selling and sometimes closing one another. Right now they’re all friends. Or so they say. They’re each so different that it’s hard to even think of them as competitors. Ultimate Indie Magic gets the beards and the FTW narrative. Ultimate Corporate Six-pack-a-tron Stratton gets the Ikon Pass-toting New Yorkers.

And what is Bromley? Bromley is Ultimate Bromley. I’m not sure how else to describe it. And Bromley skiers ski Bromley. And they love the place. And why wouldn’t they? The front side is blue square glory, fall lines straight and steady, cut New England narrow through the woods. There are chairlifts everywhere, flying in all directions from the base. Old doubles mostly. How ski areas once were before they simplified and streamlined. The Blue Ribbon side (like Pabst Blue Ribbon, like PBR – get it guys*), is a slightly shorter, black-diamond version of the frontside.

All of this oriented gloriously toward the sun. When there’s sun. In Vermont, in the winter, when it’s a thousand degrees below zero, that matters a lot. This is not a great position for snowpack. Most North American ski areas face north for a reason: shadows block the sun, preserving snow depth. But skiing into May is not the point of Bromley, or its goal. The place gets enough snow, and has a good enough snowmaking system, that it can usually make the first weekend in April. Which is when Bromley skiers are tired of skiing.

Or maybe they buy the Killington spring pass and keep going into June. In Vermont, you have options. The state has the same number of ski areas (26) as California, which is 17 times its size by area and 60 times larger by population. To succeed here, a ski area needs something compelling. Thirty miles south of Bromley lies the Hermitage Club, formerly Haystack, 1,400 vertical feet and 200 acres, a near Bromley clone size-wise. Yet the ski area has closed at least three times since its 1964 founding. No one could ever figure out how to compete with – or be little brother to – Mount Snow, the snowmaking Godzilla four and a half miles up the road. And yet Bromley, half the size of Stratton, which sits gigantic in the vista from Sun Mountain’s frontside trails, has operated for 85 consecutive seasons. It’s not like Bromley skiers don’t know they have choices. They just don’t care. Ultimate Bromley, with its little base village and its one high-speed lift and its zillion low-speed lifts and its sunshiney aspect, is home.

*That sound you hear is every hipster in Brooklyn simultaneously mounting their single-speed banana-seat bicycles and riding north toward Vermont.

What we talked about

The accidental career; Snow Valley, Vermont; Bromley in the ‘80s; the complex and interesting challenge of the ski business; where loyalty comes from; “our efforts are the same on a Tuesday in January as they are on a holiday Saturday at Christmas”; Vermont’s first chairlift; the incredible puzzle of modernizing Bromley’s snowmaking in the ‘90s; the importance of water pressure; “summer’s always been a big deal at Bromley”; grab a PBR and pop a tab for this Bromley Mountain origin story; Fred Pabst’s unlikely skiing legacy; snowmaking in the 1960s; Stig Albertsson buys the mountain; the arrival of the current owner, Joe O’Donnell, and his legacy and style as an owner; that one time Bromley owned Magic, or Magic owned Bromley, or Stratton owned Bromley, or something; why Bromley closed Magic; the return of The Golden Triangle; what happened when a fire hit Bromley 10 days before Christmas; the Fairbank Group arrives; last year’s massive upgrade to the Sun Mountain Express; why Bromley upgraded rather than replaced the lift; the incredible resilience of Hall chairlifts; the biggest challenge in running a fleet of decades-old lifts; where else a detachable lift might make sense on the mountain; a thought experiment in what would make sense to upgrade the Plaza chairlift and Lord’s Prayer T-bar; the utility and future of the old double-double; the incredible efficiency of modern snowmaking and the concomitant rise in lift-maintenance costs; managing snow quality with Bromley’s southern exposure; the Bromley snow pocket; Bromley’s lost trails; potential future glade and trail development; backcountry access now and in the future; the challenges of Forest Service expansion; “in some respects, the very best skiing at Bromley is not cut”; the base village; pricing season passes in the Epic and Ikon era and how Bromley has maintained its pricing power; rethinking the mountain’s lift-ticket pricing structure; why we’re unlikely to see a Bromley-Jiminy Peak-Cranmore joint pass anytime soon.

Why I thought that now was a good time for this interview

The Epic Pass hit New England like a tsunami. For decades, season pass prices had ticked upward like post-IPO Google stock. Then Vail bought Stowe, and everything instantly changed. As I wrote in March 2020 (a few days before I had something more urgent to write about), in an article headlined “The Era of the Expensive Single-Mountain Season Pass Is Over in the Northeast”:

For the 2016-17 season, the last before the Broomfield Big Boys scooped up Stowe, a season pass at that most classic of New England rough-and-tumble mountains was $2,313, according to New England Ski History. Pass prices to the other large Vermont resorts were similarly outlandish: $1,779 for Sugarbush, $1,619 for Okemo, $1,486 for Killington, $1,199 for Stratton, $1,144 for Bromley (!), $999 for Mount Snow, $992 for Mad River Glen, $974 for Jay Peak, $899 for Burke, and on and on.

Granted, these were probably not early season prices, and these are presumably adult no-blackout passes. But price differential from just four seasons ago – four! – is remarkable. And none of these passes, with the exception of Killington, which gave you Pico access, came with additional days at any other mountains as far as I am aware [2022 note: the Mount Snow pass, as I’m now aware, was a Peak Pass, which would have been good for unlimited access at three New Hampshire ski areas, Hunter, and all of Peak’s smaller ski areas in Pennsylvania and the Midwest]. In 2020, you can now get full unrestricted access to Stowe, Mount Snow, and Okemo for $979 on an Epic Pass [2022 note: this was the season before Vail lowered Epic Pass prices by 20 percent]. You get full Sugarbush and Stratton access for a $999 Ikon Pass, and a Beast 365 pass would be $1,344 and get you unlimited Killington and access to Sugarbush and Stratton every day of the season outside of a few blackout days.

In other words, for less than the price of a Stowe season pass four years ago, you can now have season passes to six of Vermont’s largest mountains. If you don’t mind dealing with blackout days, you could pick up a $729 Epic Local Pass and a $699 Ikon Base Pass and ski Vermont every day of the season for $1,428 (and Okemo and Mount Snow are still not even blacked out on the Epic Local Pass). And you can further reduce this by, say, picking up a $599 Northeast Epic Pass and a (if you’re renewing), $649 Ikon Base pass, which would give you blacked-out season passes to Okemo, Mount Snow, Stratton, and Sugarbush, and 10 days at Stowe and five at Killington, for all of $1,248.

I could go on. There is no need to. Skiers will figure this out for themselves, and quickly. Anyone buying a season pass in Vermont just four years ago was more or less locked into that mountain for the season, as the number of ski days required to justify the pass purchase was significant, and any days invested elsewhere probably seemed excessive and indulgent. In the three-year instant it took Vail to buy Stowe and Okemo and Peak and integrate them into a regional pass, and Alterra to buy Stratton and Sugarbush and introduce the Ikon Pass and then significantly expand access in the region, the consumer expectation has shifted from season pass as an aspirational indulgence reserved for locals and second-home owners to a bargain product that offers limitless access to not one but multiple high-quality mountains, not just across the East, but in the snowy towering West.

I then called out Bromley in particular:

In this environment, not even the burliest mountains can stand alone. Killington just conceded that. Boyne did something similar with its New England Pass last week, tossing an Ikon Base Pass in with its $1,549 Platinum-tier product, which provides unlimited access to its standout trio of Sugarloaf, Sunday River, and Loon.

All of this leaves skiers – especially mountain-hopping skiers like myself – in the best pass-shopping position imaginable. No matter which pass we buy, it will come not just with limitless days at our local mountain, but bonus or unlimited days at at least half a dozen other mountains that we can easily travel to.

All of which creates a very difficult reality for independent mountains: skiers now expect access far beyond their core mountain when purchasing a season pass, and they expect those passes to be massively discounted from what they were less than one presidential election cycle ago.

On both price and additional access, many independent ski areas are far behind. Bromley’s season pass, for example, is $925 (all prices are for adult, no-blackout passes, unless otherwise indicated). That’s early-bird pricing. It includes no free days at any other mountains, even though its parent company also owns or operates Jiminy Peak in Massachusetts and Cranmore in New Hampshire [2022 note: Bromley, Cranmore, and Jiminy Peak passes now include one day at each of their sister mountains]. It does offer some non-holiday discounts of up to half off day tickets at partner resorts, including Jay Peak.

This is a completely untenable position. Bromley is a fine mountain. It is terrific for families. It has some fun terrain off the Blue Ribbon Quad. It is very easy to get to. But it is right down the road from Stratton, which is far larger, has a far more sophisticated lift network, and is on the Ikon Pass, meaning a pass to Stratton is only $74 more than a pass to Bromley and also includes a pass to Sugarbush, days at Killington, etc., etc. Unless you have a condo on the mountain and you ski there and only there and have for years and years and have no aspirations or intentions of going anywhere else ever, there is no way to justify that pass price with no access to any mountain other than your own in today’s competitive ski pass environment.

One of two things needs to happen in order for independent mountains to remain competitive in the season pass realm: they need to join a coalition of other independent ski areas to offer reciprocal free days at one another’s mountains for passholders, or the price needs to come way down. And in most cases, the answer is probably some combination of both of those things.

Well I was wrong. Bromley never joined a pass coalition and its pass price keeps increasing, and yet every year, the mountain sells more passes. So I’ll own my mistake. My template was too simplistic, too focused on price and variety and size as a skier’s primary motivating factors, too anchored to the assumption that all skiers were like me, seeking the most mountains for the lowest cost. It would have been like saying Whole Foods business model sucks because Kroger has larger stores and sells groceries for less money. Consumers will pay a premium for exclusivity and quality. And Bromley offers both: good snow, fewer people. A predictable, repeatable experience for a tight community of families and condo owners. These things matter more than I had supposed.

Select independent ski areas all over the country are thriving in the megapass era by snubbing the trends of the megapass era: Wolf Creek, Mt. Baker, Bear Valley, Whitefish, Bretton Woods, Wachusett, Plattekill, Holiday Valley. Part of this is Epkon burnout, refugees seeking respite from the crowds. Part of it is atmosphere and community, skiers buying into a gestalt as much as a place or activity. Bromley operates in one of the toughest neighborhoods in skiing, seated within a two-hour’s drive of dozens of competitors, many of them bigger and cheaper, with more terrain variety and more snowfall and more and faster lifts. And yet the Sun Mountain keeps winning. There’s a reason for that, and I wanted to figure out what it was.

What I got wrong

I stated in the interview that Joseph O’Donnell had purchased Bromley in 1990, intimating that marked the start of his involvement with the ski area. Cairns points out that O’Donnell had worked with Bromley beginning in the 1980s.

Why you should ski Bromley

Mount Snow and Stratton, nice as they are, tricked out as they are, have downsides. Especially on weekends. Especially midwinter. Neither does a great job managing skier volume, and neither seems particularly interested in trying. I don’t know how much that really matters. It’s New England, and skiers expect crowds. It’s all part of the experience, like overgrooming and boilerplate and safety bars dropped on your dome before the chair is out of the barn.

How to escape the human anthill ski experience? Well, you could join the Hermitage Club, which at last check-in cost $50,000 upfront and $15,000 annually thereafter. You could ski Magic, which is uncrowded but snowmaking-challenged, with just 50 percent of the mountain covered and one fixed-grip double to the top (though the Black Quad may finally be close to launch). Or you could ski Bromley, with the snowmaking and grooming firepower of its bigger corporate neighbors, but without the mosh-pit atmosphere. Unlike most of Vermont, the place is tolerable even at its busiest.

And the sunshine effect is real. Stratton is often abandoned after 2:30 p.m. The sun dips, the snow bricks up, and everyone leaves. When the clouds aren’t bunching heavy over New England and the wind stays down, Bromley is just a more pleasant place to be. It doesn’t have the tough-guy terrain like Killington or the expanses of glades like Stratton. And it doesn’t need them. Bromley, the Ultimate Bromley, is just fine being exactly what it knows it has to be.

Podcast notes

We go deep on Bromley’s long history, but New England Ski History has a great overview of the ski area’s development, going back to the wild early days of recorded Vermont history.

Bill and I discuss the lost Snow Valley ski area extensively. Though this little spot, parked off Vermont state highway 30 between Bromley and Stratton, closed in 1984, it remains popular among backcountry skiers. Someone still maintains several runs, and the property was recently listed for sale (it was scheduled for auction in September, but I’m uncertain how that went). While it’s highly unlikely that anyone could redevelop Snow Valley as a lift-served ski area, it could become New England’s version of the uphill-only Bluebird Backcountry ski area in Colorado. Here’s a 1982 trailmap:

Bill discusses the rising cost of everything, but point in particular to the exploding price of chairlifts. He notes that the Sun Mountain Express cost Bromley $2.7 million in 1997, and estimates that it would run $7 million to install a similar lift today. Had chairlifts followed general inflationary trends, the lift would run around $5 million today.

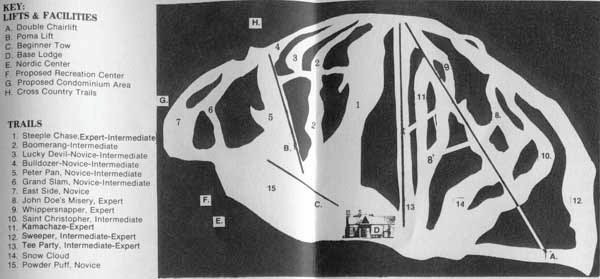

Bill references a 1950s trail called “Bromley Run,” that ran off the summit and didn’t return to the lifts. You can see it marked as trail 10 on this “Big Bromley” trailmap from 1950:

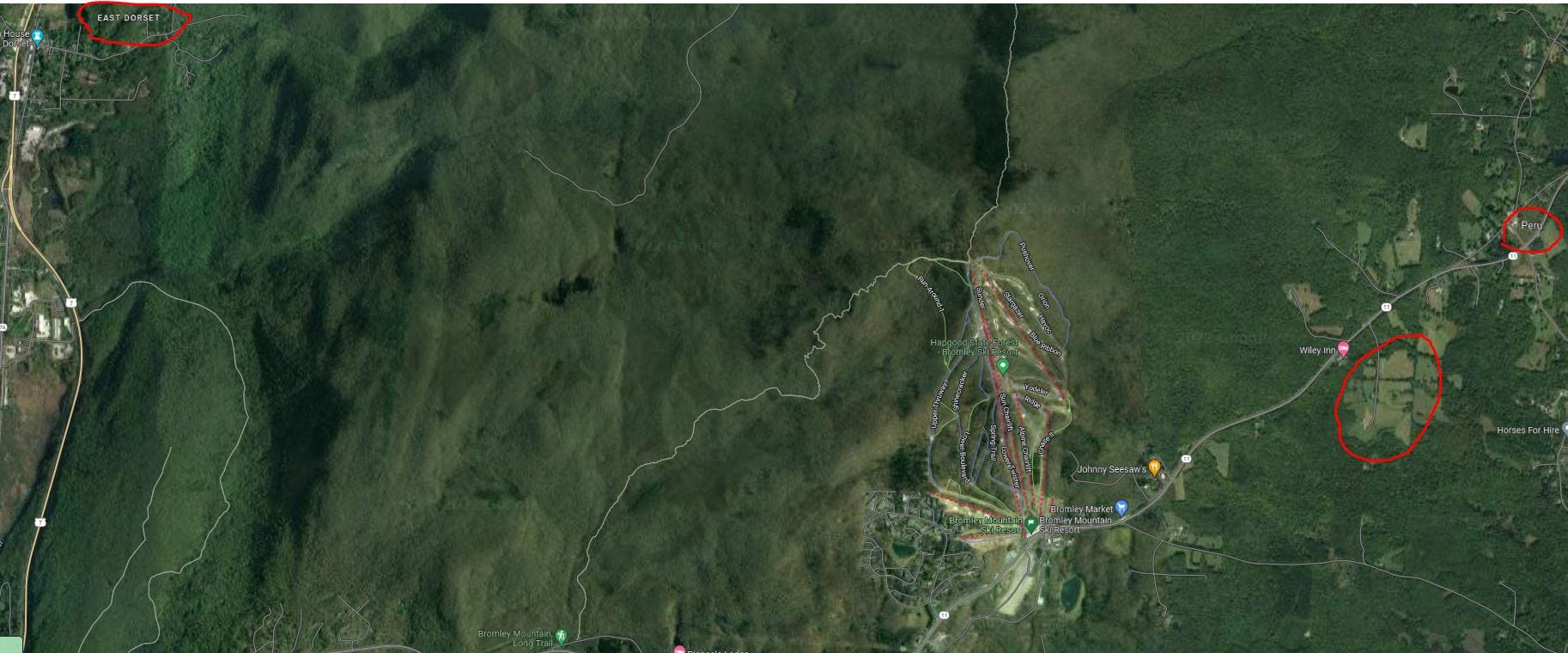

Bill and I discuss potential terrain expansions (unlikely), and the possibility of backcountry skiing – possibly guided – from the summit down to Peru, to the east, and East Dorset, to the northwest. He also refers to the Best Farm quite a bit, which is the large circled area off highway 11. The Fairbank Group’s website currently has this space scoped for real estate development. Here’s the ski area in relation to these various areas:

The Storm publishes year-round, and guarantees 100 articles per year. This is article 120/100 in 2022, and number 366 since launching on Oct. 13, 2019. Want to send feedback? Reply to this email and I will answer (unless you sound insane, or, more likely, I just get busy). You can also email skiing@substack.com.

Share this post