Wolf Ridge, North Carolina Changes Name to “Hatley Pointe”

Mountain, under new ownership, teases significant progress on snowmaking upgrades and lodge renovation

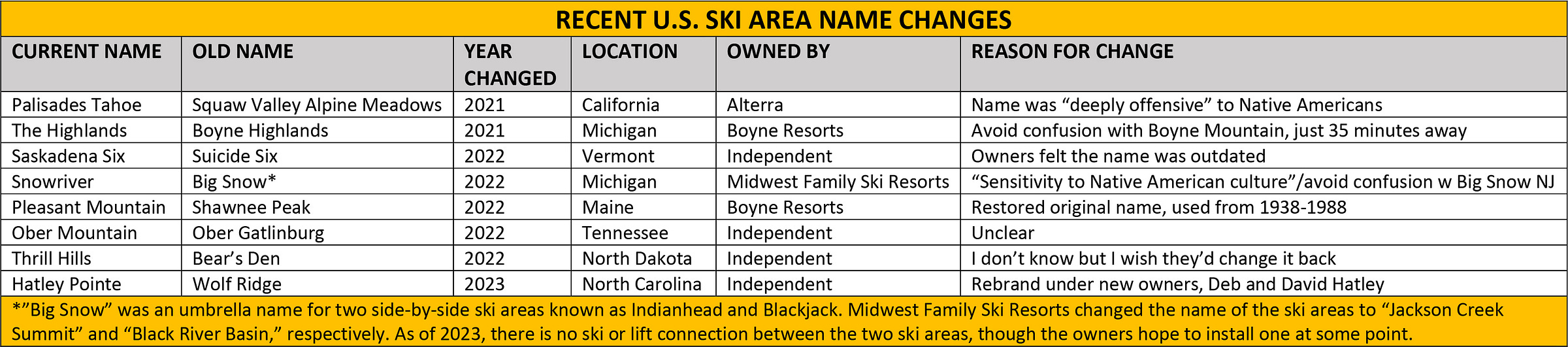

Ski areas change their names for all sorts of reasons. Palisades Tahoe, California; Saskadena Six, Vermont; and Snowriver, Michigan ditched monikers that had aged poorly: Squaw Valley, Suicide Six, and Indianhead, respectively. Boyne Highlands, Michigan became “The Highlands,” mostly to avoid decades-long confusion with nearby Boyne Mountain. And Boyne Resorts restored the Pleasant Mountain name to its newest property, then known as “Shawnee Peak,” 34 years after a Pennsylvania resort operator had changed the original name to match his Poconos ski area. Here’s a look at all of the U.S. ski area name changes in the past two years:

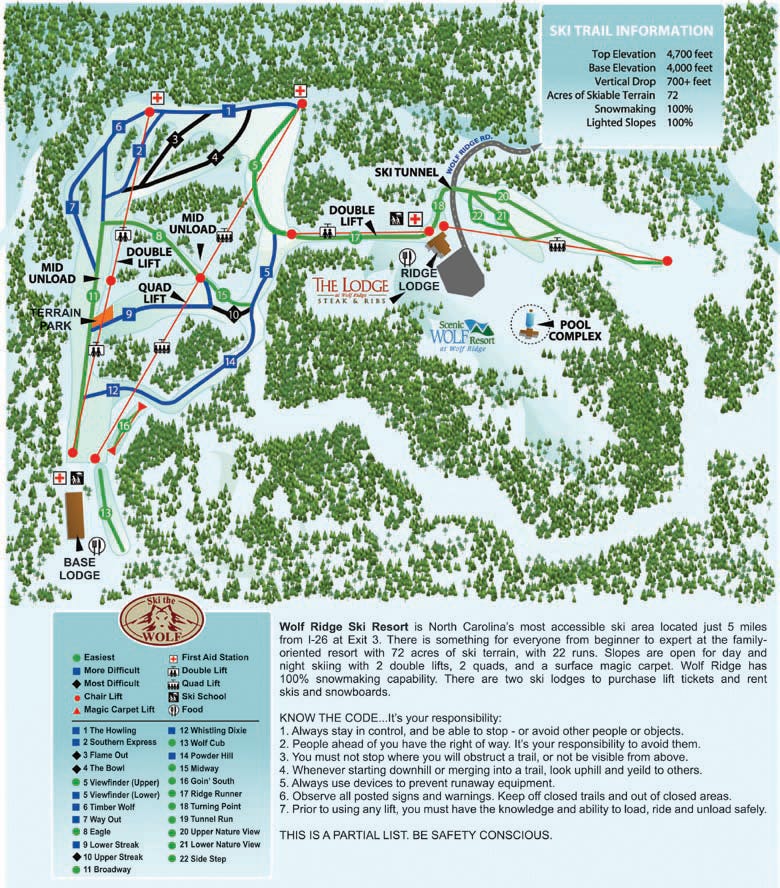

The last one on that list is official as of today: the North Carolina ski area known as Wolf Ridge will become “Hatley Pointe” under its new owners, Deb and David Hatley. The resort announced the name via this video, made public today:

The resort’s new website is also live. “We want to give the mountain a new era and a new life,” Deb Hatley told The Storm in May. This is at least the second name change for the ski area, which was known as “Wolf Laurel” through at least 2005.

The name change, however, is a footnote compared to the massive renovations underway on the mountain. The video features Deb Hatley seated among the gut-renovated base lodge. The scale and energy of the project echoes the complete overhaul of Timberline, West Virginia in 2020. A declining mountain, stripped to its bones and reborn with a full-service restaurant and VIP season passholder lounge. Modern, appealing beyond the skiing itself, almost grand. A ski resort, rather than a simple ski area.

From a skiing point of view, the video underscores the extent of the top-to-bottom snowmaking upgrades, with 16-inch pipe strung up the incline. Here, Hatley, a self-described novice skier, reassures us that she understands the first and only thing that matters to a Southeast ski area: snowmaking.

“Our temps are marginal, and we really have to capitalize on those colder climates and colder weeks and days,” she says in the video. “And so that's a really big piece that we're redoing, and I believe that people are going to notice and really appreciate it.”

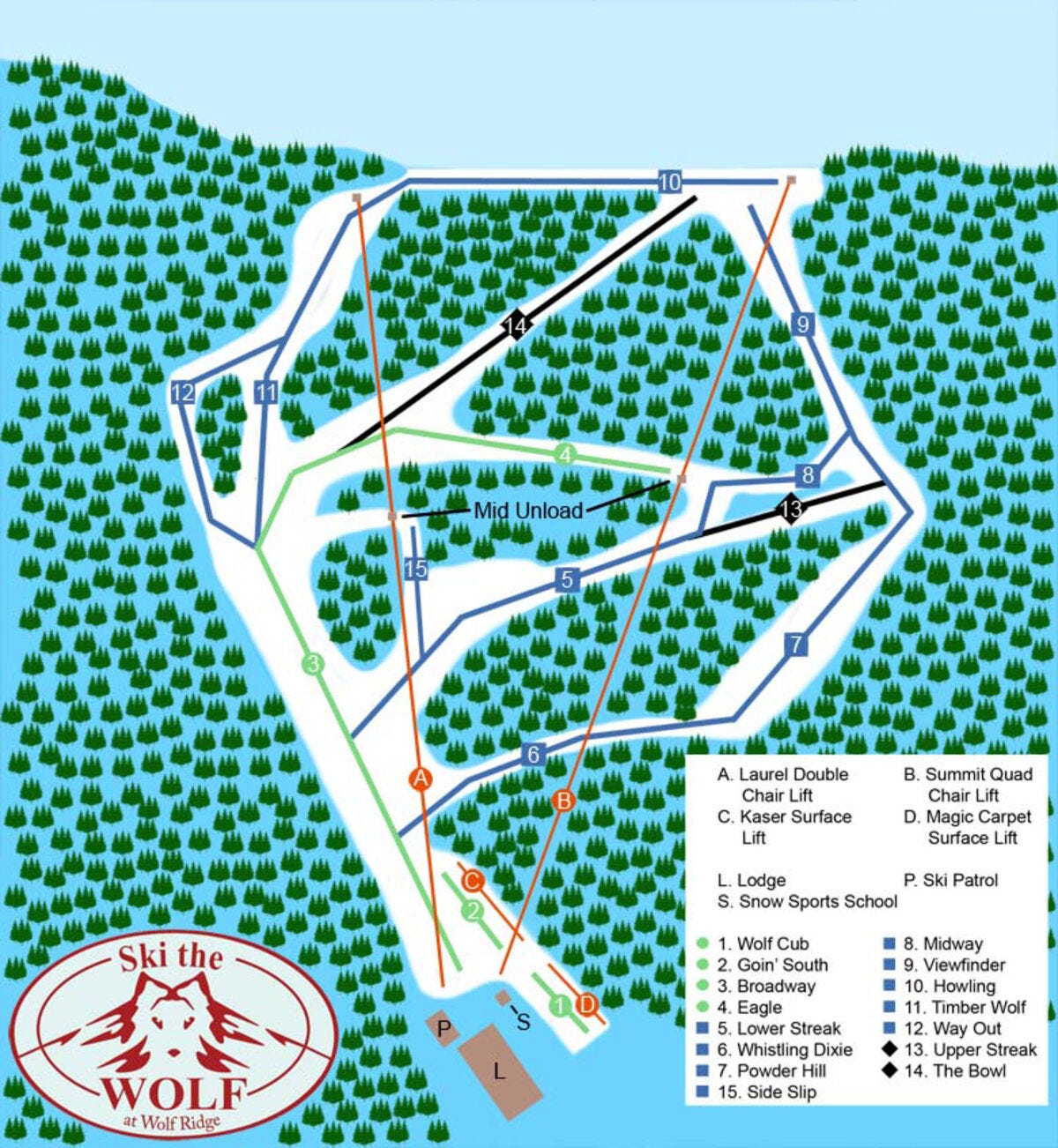

There is still plenty to do, of course, but pumping up snowmaking output was crucial for a ski area that didn’t manage to make it out of February alive this past season. The upper-mountain Ridge Lodge, burned to the ground in 2014, needs to be rebuilt. The Hatleys intend to revive the dormant terrain and lifts – a double and a quad – around that lodge, and to upgrade the frontside double chair, possibly with a high-speed lift, Deb told The Storm in May.

Those projects will take time. What the Hatleys can implement faster is a cultural shift to a more boutique, service-oriented experience.

“The service side of things is, I feel, going to be one of our biggest strengths,” Deb says, alluding to the Hatleys experience running high-end resorts. “That is something that's embedded into our culture of our company, and something that we are going to be really training the future staff here in this place as to, you know, you are here to serve these people.”

Much of the rough-and-tumble ski industry is allergic to such explicit appeals to skiing’s fluffier side. Hearty bearded bros pounding a tailgate breakfast of PBRs before powder-bounding off a 60-year-old double chair for seven hours is the ski-hero archetype of the moment. But it does not really capture the sport’s zeitgeist. Skiing is mostly families, mostly intermediates, mostly three-laps-and-a-lunch-break Saturdays. Hatley gets this.

“They're not just here to go and ski and snowboard down a mountain,” she says. “They're also here to create unforgettable experiences with their family and their kids. And that's something that I'm big about. It's something that matters a lot to me, and that's like, the heart of myself is making someone feel very special and appreciated and thought about whenever they come to a space.”

This sort of message plays very well in the Southeast, where most of the surviving ski areas are stapled to a larger, year-round resort. For the past several years, Wolf Ridge has been a shrinking, under-invested property that could rarely hack out a three-month ski season. The ski area has closed in February four times since 2018, and only made the first week of March in the other two seasons. That is not a sustainable business, especially in the Epkon era, when Charlotte skiers can hop a 7:05 Delta flight, touch down in Salt Lake at 9:25 in the morning, and be skiing Snowbird or Park City by lunchtime.

Hatley Pointe is a reset, on the brand and on a stale business. I’m sure some locals will be nostalgic for the old name, with its wily connotations of beastly, thrilling nature. I’ll miss it too. But most will forget “Wolf Ridge” the moment they step into that new lodge and understand that “Hatley Pointe” signals a new, sustainable era for a tough business in a tough climate.

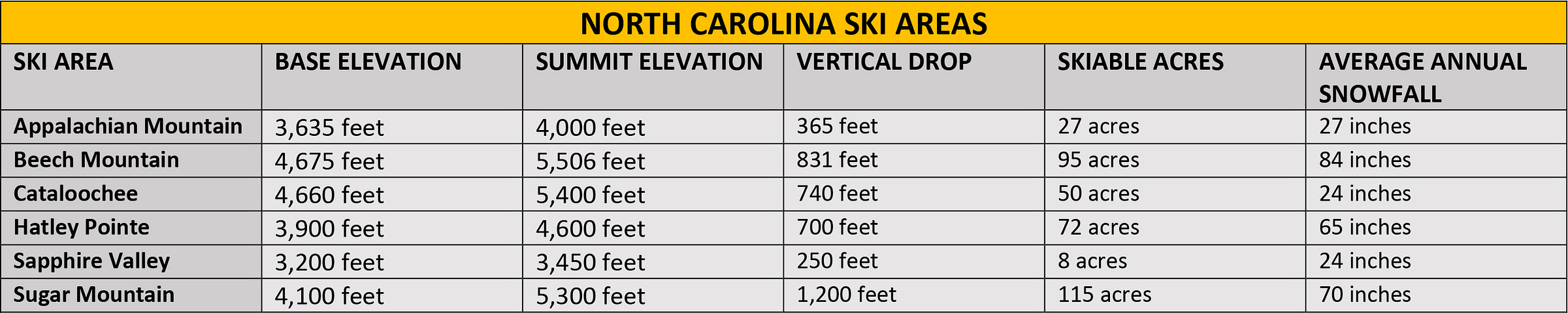

North Carolina skiing doesn’t get much attention nationally, but it is an incredibly important ski market. It is the ninth most-populous state in America, a rising Sun Belt power with a growing upper-middle-class population. Georgia, the eighth most-populated state, and one with zero ski areas, sits just south. Despite this huge regional population, North Carolina is home to just six active ski areas:

Beech and Sugar Mountain have aggressively modernized, installing a combined eight new chairlifts since 2015. That sort of investment is not possible without passionate skiers dumping their paychecks into the cash register. The market exists to support a version of Hatley Pointe that resembles – or even surpasses – its competitors. The ski area owns a respectable vertical drop, passable terrain, and an incredible location – just a few miles off Interstate 26, a short drive from Asheville. It has good bones, as the developers say, but bad skin – crummy snowmaking, two dormant lifts plus a 52-year-old SLI double chair and a 1988 Doppelmayr quad. It’s fine for beginners, but most will quickly lose interest and hop a flight west.

To survive long-term, Hatley Pointe needs to evolve into a place that skiers covet as a homebase between their trips west. That means modern facilities on the hill and off. The Hatleys’ first moves are promising. Anyone who calls this bump home – or is considering it – should feel really good about what they’re seeing so far.