Telluride, Citing Impasse with Ski Patrol, to Close Saturday

Strike is set to start one year to the day after Park City patrollers walked out

Telluride Ski Resort plans to close on Saturday, Dec. 27 in response to a planned strike by the mountain’s ski patrol, the resort announced on Wednesday, saying that “Telluride Ski Patrol has rejected the resort’s last, best, and final offer.”

“As a result of the Ski Patrol’s decision to strike, we have made the difficult decision to close the resort on Saturday,” said Telluride Ski Resort representative Steve Swenson. “At this time, we do not know how long the strike will last. We will continue working on a plan that allows us to reopen safely as soon as possible.”

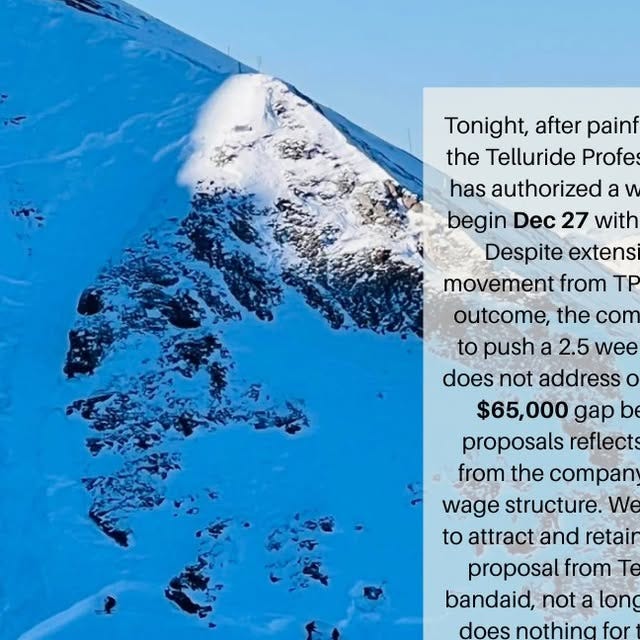

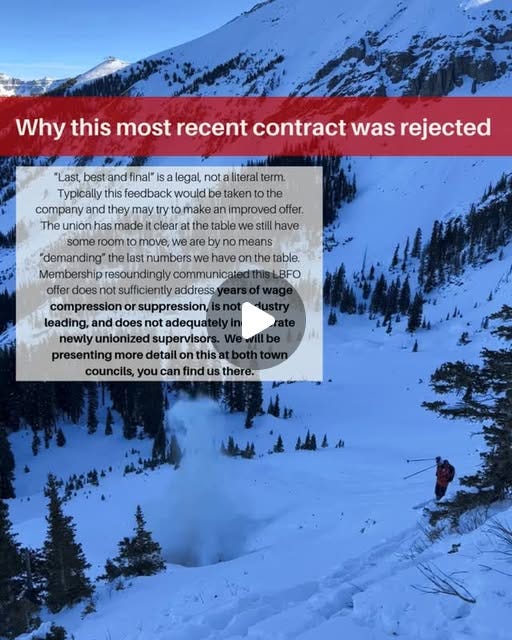

Telluride’s ski patrol, which organized in 2015 under United Mountain Workers (UMW), announced the strike earlier Wednesday, citing a “$65,000 gap between 3 year proposals” that “reflects unwillingness from the company to fix a broken wage structure.” Without citing specifics, the patrol’s public statements repeatedly cite a “broken wage structure” that has made it difficult to recruit and retain patrollers with the expertise needed to manage Telluride’s technical, treacherous terrain.

Should the strike proceed, it would be the second such action by a UMW ski patrol over the past two Christmas holiday weeks at a major western resort in the U.S. Last year, approximately 200 patrollers at Park City Mountain Resort, America’s largest ski area, organized a nearly-two-week-long strike beginning Dec. 27. Vail Resorts, which owns and operates the ski area, kept the resort open for the strike’s duration, but with a constrained terrain footprint that spiraled into long lift lines, bad press, and disgruntled skiers. The company later offered 2025-26 credits to impacted guests, and the negative attention surrounding the strike likely contributed to CEO Kirsten Lynch’s abrupt departure in May.

Telluride owner Chuck Horning, who has recently (well, maybe always) feuded with the town over lift ticket taxes and a replacement for the town gondola, blamed patrol for the pending shutdown.

“Telluride Ski Resort did not make the decision to strike, nor did we choose the timing,” Horning said in a statement released by the resort. “We are deeply disappointed that the Ski Patrol has chosen to take this action during such a critical time for our guests, employees, and the broader community. The Ski Patrol has previously stated in public town meetings that a strike would be their ‘nuclear option.’ We are concerned about the significant impact this decision will have on our community.”

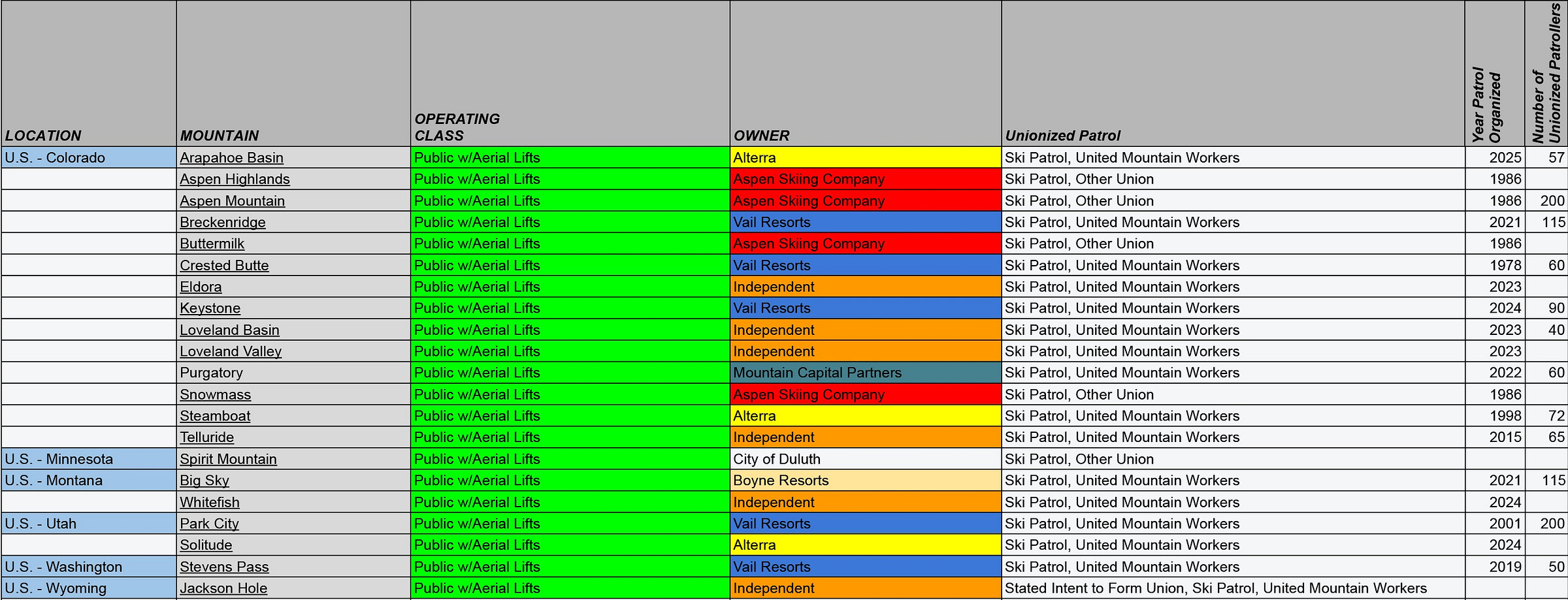

Unionized ski patrols have nearly doubled in number over the past four years, with 10 new units organizing across independent and conglomerate-owned ski areas. More than 1,100 patrollers at large destination western resorts have formed chapters of UMW, which is organized under the 700,000-member Communications Workers of America union. In November, patrollers at Jackson Hole, Wyoming took initial steps toward unionization.

So now what? What happens if a major U.S. ski resort closes during the country’s biggest holiday week? Can they actually do that? Here are four initial thoughts as we watch this storm roll through.

1) Can Telluride really close?

Telluride is one of 116 U.S. ski areas operating on U.S. Forest Service land. While small portions of the resort footprint fall on private or town land in Telluride and Mountain Village, the rest of it belongs to the rest of us – at least if we can afford the lift ticket. Does the Forest Service have no role in compelling Telluride to find a solution here?

If there isn’t anything the government can do immediately, can they do something long term? Telluride has been dysfunctional for years, churning through top leadership and failing to upgrade infrastructure at rates commensurate to other Colorado destinations. The breadcrumbs always seem to lead back to Horning, who seems to like fighting and blaming everything on everyone else rather than finding solutions. Can’t the Forest Service just say “yeah you’re not good at this,” cancel the lease, and seek a new operator? I could find you 10 who would do a better job and who would be there with a blank check tomorrow.

2) What is the actual value of a big mountain ski patroller?

Were I asked to draft a job description in search of big-mountain patrol candidates, I would probably come up with something like this: seeking ski patrollers for Big Time Mountain. Ideal candidate will possess a mountain goat’s agility, a meteorologist’s grasp of weather and snowpack, an ER doctor’s trauma-response capability, a monk’s demeanor, and an ’80s action-hero’s adeptness with handheld explosives. Also must be an expert skier. Who likes to wake up at 2 a.m. And doesn’t mind living two hours away because we are paying just barely above minimum wage for this highly specialized job. Because you get a free ski pass I guess.

Yeah I know I know – the market decides what you’re worth. Well, right now, the market is telling us that a class of employees who organized sparingly for the past five decades is suddenly doing so in accelerating numbers. It’s possible that recent raises for frontline staff occupying less training-intense roles have made highly trained patrollers feel less valued. And no one but patrollers – other than a pair of lift-maintenance teams – have pushed unionization efforts. Ski areas seem to be asking “what’s the smallest amount I can get away with paying these people,” rather than “what are these mountain ninjas worth to our operations?” And the best way to determine that value may be…

3) Can we UAW this thing?

When I hosted UMW President and Park City patroller Max Magill on the podcast earlier this year, I asked him if the eventual goal was one patrol union that could bargain as a block across resorts, as United Auto Workers does across, say, Ford plants, rather than via satellite divisions with 50 members here and 80 there. He acknowledged the benefits of such a system without committing to any particular direction.

The ski industry is at an inflection point here. The path of least resistance would likely be for ski area operators to proactively approach both the UMW and their own patrols, and say, “hey, we see this trend happening, and we want to work with you to make sure you have what you need to do your job and are compensated enough to live in this town, but we think it would be better for everyone if we negotiated industrywide – or at least region-wide – standards rather than negotiating dozens of individual contracts.”

Or the operators could fight, which would swim against prevailing public sentiment, mess up people’s vacations, and probably cost more to repel than just pay for. Telluride Ski Patrol says the amount of the negotiating gap here is $65,000 over the three years of the contract (though the exact amount is unclear). How much will Telluride lose by closing this week?

4) We need to admit that Telluride – and the American mountain town in general – is broken

Anyone else remember this commercial?

The script is succinct, masterful, sticky. Thirty-two years later, I still ask smaller merchants if they take Amex before tapping my card because of it:

About 65 miles south of the nearest stoplight, and two miles up in the Rocky Mountain sky, you’ll find skiers’ heaven, also known as Telluride. The skiing’s perfect, and the views are even better. Whether you’re going to extremes, or just going for a lesson, don’t go without your Visa card. Because at Telluride ski resort, they’ll let you take The Plunge, but they won’t take American Express.

Visa: It’s everywhere you want to be.

I’d never heard of Telluride when that commercial dropped, sometime around late 1993. I’d skied twice and hadn’t cared for it. But that was in the Midwest, on dirtbumps where you could see the bottom of the hill from the top, and not much else but the bottom since the top was only 200 feet in the air. Here was something else: Colorado, wild, mythical, exotic. It was a place that seemed impossible to believe in.

Looking back from 2025, the version of Telluride bite-snapping across the screen is just as hard to believe in, but for entirely different reasons. Yes, the lack of helmets, the skinny skis, the sticky wickets, the neon, and the sweaters all timestamp the era. But the spot’s greatest anachronism, to a 2025 viewer, is the casual, skis-over-shoulder meandering through downtown, still quaint, snowed-in, slightly ramshackle, a place not yet fully emerged from its 1970s nadir as near-dead end-of-the-road former mining town.

Depending upon your point of view, skiing, which formally arrived in 1972, either saved or killed Telluride. As an international brand in a globalized world, this 2,000-acre ski resort (tied for just 34th largest in America) is an unqualified success, with a reputation far bigger than the skiing itself. As a functioning town where people who don’t own nine helicopters can afford to live, it’s a failure. Average home prices in the town of 2,607 have more or less doubled in the past five years and currently hover just over $2 million, according to real-estate site Zillow. Median household income ranges from $75,000 to $100,000, depending upon the source.

“The unfortunate reality is that wages at Telluride have fallen behind and high costs of living have resulted in higher than historical turnover rates, leading to short staffing and the erosion of our institutional knowledge,” Telluride Patrol wrote recently on their Instagram page:

What broke Telluride? A lot of things, which we can summarize as a failure to build enough housing and a failure to manage what the housing that is built is used for. This isn’t unique to Telluride, which is a good thing. As an “abundance agenda” that pushes for more housing and infrastructure with less regulation gains momentum across the country, we will eventually find a ski town that figures out how to fix itself.

From all the reporting, it sounds like the owner is arrogantly self-centered, and not interested in supporting the community or the professional patrollers. It also sounds like the owner probably doesn’t care about the cost of the patrollers contract, but rather is looking to impose his my-way-or-the-highway business strategy. That’s sad. The community, the customers, and the employees all deserve better.

As Stuart Winchester noted, Telluride is mostly located on United States Forest Service (USFS) land. That gives the general public an interest in the safe operation of the ski area, both as a recreational opportunity, and as fee payer supporting the national treasury.

The Telluride federal permit requires an area specific operating plan, which in turn requires sufficient and trained emergency responders familiar with the terrain. No doubt they must also have an ATF permit for explosives, which has additional requirements usually handled by professional ski patrollers. I haven’t read the current Telluride permit or operating plan, although they are available through a FOIA request (expect a long delay on any FOIA requests under current federal policy). The basic permit structure is available at https://www.fs.usda.gov/specialuses/documents/FS-2700-5b%20092020Final-RE.pdf, and indicates the level of control the regional USFS office would have over operations.

USFS can suspend the permit if the ski area isn’t able to meet established safety standards, which probably triggered the owners decision to shut down temporarily, rather than face a suspension. That’s a pressure point I hope the patrollers union will leverage.

First things first, Merry Christmas Stuart and all the best for the new year. Professional ski patrols have been historically under appreciated and under paid. When Dick Bass still owned Snowbird he fired all or almost all of the patrol over wages and hired cheap inexperienced replacements. He appropriately caught a bucket load of crap but as a self described large mouth bass he didn’t seem to care. Meanwhile he filled the lobby of the Cliff Lodge with priceless antiques and expensive art but no place for guests to work on skis. I recall chatting with one evening and wondering if he knew that a 207 wedged perfectly in his marble bathrooms to be tuned. I did, I was carefull, didn’t hot wax n scrape and didn’t tell Bass. Some of the patrol her fired were my friends. I prime directive of operating a ski area is no patrol, no operate. As an adventurous skier I always appreciated the skills of the professional patrols but not the NSP amateurs who frequently have the ski skills and judgement of Florida Man. Pay ski patrol more and the fat corner office boys less.