Should Kids Under 18 Ski Free? Antelope Butte, Wyoming Offers a Test Case

“I want to send a resounding and clear message that we need to do something different” – Antelope Butte board member and Indy Pass and Entabeni Systems Director Erik Mogensen

Sometimes kids ride for free. On airplanes before they turn 2. At Disneyland before their third birthday. Both my kids excel at the art of turnstile-ducking in the New York City Subway, where kids up to 44 inches tall (this height is widely flouted), ride for free.

Skiing has versions of this. Kids 4 and under get a free Epic Pass (Ikon charges $149). Mountain Capital Partners’ Power Pass – good at Arizona Snowbowl, Purgatory, and the rest of the company’s portfolio – is free for kids 12 and under, with no adult pass purchase required. Many of Powdr’s mountains toss in a youth pass with the purchase of an adult pass: Snowbird passholders can add anyone 18 or under on for free; the age drops to 15 at Copper; Pico offers complimentary complementary passes up to age 12, but the adult passholder must be the kids’ legal guardian. There are also a handful of community-operated, surface-lift-only ski areas that are free for anyone, anytime: Harrington Hill, Vermont; Newcomb, Dynamite Hill, Emery Park, and Chestnut Ridge, New York; Tower Mountain, Michigan; Blizzard Mountain, Idaho. But most of these operations are semi-functional, and often go multiple winters without spinning the lifts at all.

But no ski area, as far as I know, has made a season pass offer so sweeping and simple as that of Antelope Butte, Wyoming, which, late last week, announced that any child age 17 or younger could snag a 2024-25 season pass to the mountain, with no adult purchase required.

It is a gesture that is at once noble and quixotic: a gorgeous but remote and low-volume ski area opening its slopes to anyone who can manage to travel there across the Wyoming vastness. It is either a pilot program in crafting a youth-skier pipeline or a low-consequence wilderness experiment by a ski area seeking alternate operating models. Perhaps both. Either way, it is the latest experiment by Entabeni Systems and Indy Pass owner and Antelope Butte board member Erik Mogensen to nudge independent ski areas out of engrained habits and along more financially sustainable paths.

1,000 vertical feet 1,000 miles from anywhere

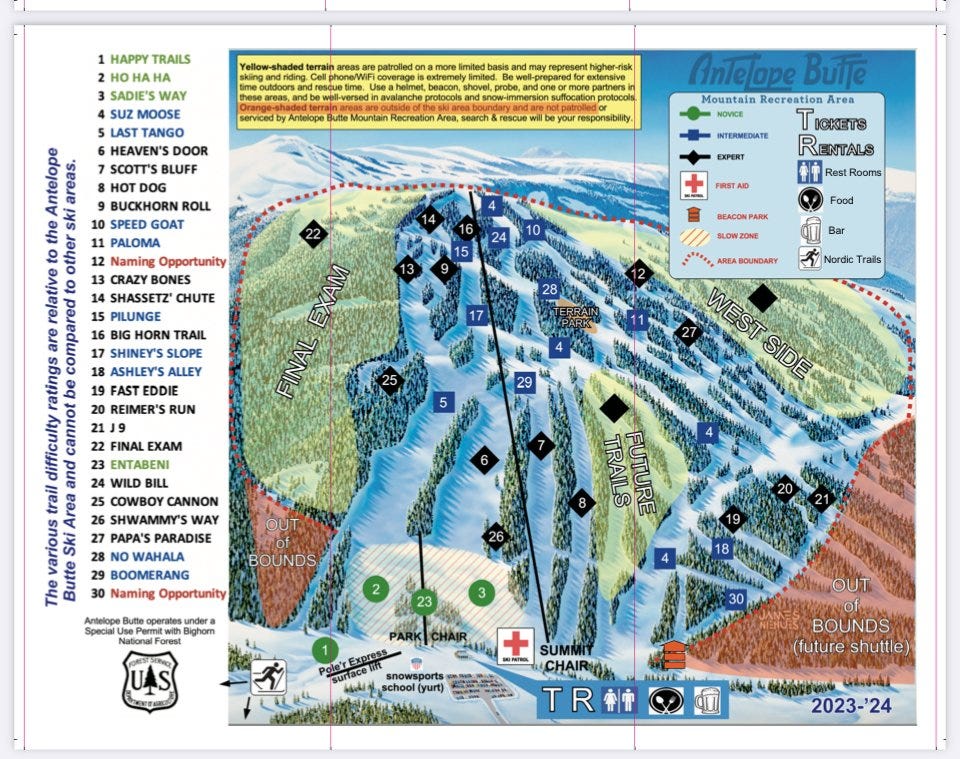

This is Antelope Butte, Wyoming:

The Summit Chair is a Riblet double that rises 960 vertical feet (from 1962 to ’88, it was the Iceberg Ridge chair at Crystal Mountain, Washington) and serves the ski area’s entire 225 acres. Like everything in Wyoming, the 10th-largest but least-populous U.S. state, Antelope Butte is remote, lodged on the west side of the Bighorn National Forest. The closest town is Shell, population 83, half an hour west. Greybull, population 1,669, lies 15 minutes beyond that. Bighorn County, which at 3,159 square miles is twice the size of Rhode Island (1,545 square miles), is home to just 11,521 residents, roughly one percent of the New England state’s population of 1,095,962.

All of which can be interpreted in a couple of different ways: 1) Dang, this is a rough neighborhood to try and run a small ski area, or, 2) This is exactly the kind of place where establishing a sustainable model for a small ski area is crucial to the future of snowsportskiing.

Both, it turns out, are true. Antelope Butte shuttered in 2004 and sputtered back to life around 2018. In that interim, there was really nowhere else nearby to ski. There are not as many ski areas in Wyoming as one might suppose: just 10, and the next closest is Meadowlark, 109 miles and more than two hours by car to the south. Sleeping Giant (which failed to open this past winter) sits more than three hours west. The closest big ski area is Red Lodge, more than three hours northwest over the Montana border.

A citizens group called the Antelope Butte Foundation (ABF) raised millions to bring the ski area back online as a nonprofit. The foundation re-activated the lifts, renovated the lodge, joined the Indy Pass. A controversial board shake-up last year simplified the ABF’s governance structure. Among the new board members was Mogensen, who’s assumed a sideline as a sort of benevolent activist investor of lift-served skiing, a third party who concocts novel ways for marginal operations to sustain themselves in the rapidly changing, ever-more-technology-dependent marketplace.

In October, Mogensen forestalled the previously announced closing of 88-year-old Black Mountain, New Hampshire by assembling a group to seek new owners. In December, he was at the center of another group that provided financial assistance to re-open long-shuttered, natural-snow-dependent, roughneck Hickory, New York. Entabeni itself is built on providing e-commerce and other tech to ski areas that would never be able to develop these digital solutions themselves, often with no upfront fee.

By waiving the child’s admissions fee at Antelope Butte, Mogensen is pushing a mission that, he says, is larger than the financial success of one small ski area.

“As a board, we feel our primary obligation as a non-profit ski area is to support youth and the greater community, rather than raising prices to build more lifts and expand facilities,” said Mogensen. “Our mission is not to create a big fancy ski area, but to get more people skiing and riding more often. Price is the biggest barrier in skiing right now.”

With that barrier out of the way, Antelope Butte has another frontier to cross: distance.

How far will they come to ski a local (and is that even the point)?

Roughly .17 percent of the U.S. population – 581,000 people – live in Wyoming. And most of them live nowhere near Antelope Butte. The state’s most-populous county, with around 100,000 residents, is Laramie, home to Cheyenne, which is approximately twice as close to mega-huge Steamboat (three hours), as it is to tiny Antelope Butte (5 hours and 40 minutes).

So Antelope Butte is not Jackson Hole. We already knew that. And, barring some sort of mass bussing movement, it is unlikely that many kids from farther than Sheridan, population 19,235 and an hour and 15 minutes east over the Bighorns, will cash in their Antelope Butte season pass.

But could the notion of unshackling skiing from its cost, at least for kids, prove such a powerful growth catalyst that it somewhat re-orders skiing’s broader business model? A similar recent European experiment in free soccer tickets suggests the strategy could at least reset local perceptions of Antelope Butte. From The New York Times:

Neither Paris F.C. nor St.-Étienne will have much reason to remember the game fondly. There was, really, precious little to remember at all: no goals, few shots, little drama — a drab, rain-sodden stalemate between the French capital’s third-most successful soccer team and the country’s sleepiest giant.

That was on the field. Off it, the 17,000 or so fans in attendance can consider themselves part of a philosophical exercise that might play a role in shaping the future of the world’s most popular sport.

Last November, Paris F.C. became home to an unlikely revolution by announcing that it was doing away with ticket prices for the rest of the season. There were a couple of exceptions: a nominal fee for fans supporting the visiting team, and market rates for those using hospitality suites.

Everyone else, however, could come to the Stade Charléty — the compact stadium that Paris F.C. rents from the city government — free.

In doing so, the club began what amounts to a live-action experiment examining some of the most profound issues affecting sports in the digital age: the relationship between cost and value; the connection between fans and their local teams; and, most important, what it is to attend an event at a time when sports are just another arm of the entertainment industry. …

By opening its doors, the club believed it might lift attendances, attract families and nurture some long-term loyalty. But it was just as concerned with telling people it was there. “It was a kind of marketing strategy,” Fabrice Herrault, the club’s general manager, said.

“We have to be different to stand out in Greater Paris,” he noted. “It was a good opportunity to talk about Paris F.C.”

Months later, most metrics suggest the gambit has worked. Crowds are up by more than a third. Games held at times appealing for school-age children have been the best attended, indicating that the club is succeeding in attracting a younger demographic.

Paris F.C.’s tickets were never desperately expensive — Aymeric Pinto, a fan who has been attending for a decade, said that attendees had been paying the equivalent of only about $6, but abolishing even that shallow barrier has made a noticeable difference. …

Still, for Paris F.C., the overall pattern has been encouraging. The free-ticket strategy will cost the club about $1 million — a combination of lost revenue and added spending on security and staff — but the company line, and supporters’ feedback, is that it has been worth it.

In the case of Antelope Butte, the idea is that kids who would not otherwise ski will fall in love with it at the hill, and will not only become adult passholders, but customers at larger resorts throughout the industry.

“I want to send a resounding and clear message that we need to do something different, and that we're willing to do something different, and we have to try different things in order to get a different and better result,” Mogensen told The Storm.

The experiment is already yielding business results. Antelope Butte’s early adult pass sales have more than doubled over this time last year, and overall pass revenue is up 139 percent, even with 803 free kids passes claimed as of Wednesday morning. Donations have surged 5,000 percent.

“Bottom line revenue is up significantly, even though we gave the pass away for free under 18,” Mogensen said.

As with Paris F.C.’s soccer experiment, Antelope Butte will absorb the initial cost of the free passes, primarily, Mogensen said, through board member-provided subsidies. Long term, “we believe that we can support it every year through the operation of the ski area,” he said.

The lift ticket, of course, is just a portion of the cost of skiing. The board, Mogensen confirmed, is examining ways to provide children with equipment rentals and transportation to and from the hill, particularly on weekends.

If Antelope Butte can fill in those blanks, Mogensen believes that he’ll be close to solving an old skiing problem that Entabeni Systems’ data has made clear: kids don’t tend to ski unless their parents do.

“There's an almost one-to-one connection between kids that are on the hill and some relationship to a parent that's on the hill or bought a product,” Mogensen said. “There just were very few kid-only customers across Entabeni over the last few years. And that's because skiing takes a lot of work. It's a lot of money, it's a lot of expense, a lot of equipment.”

A data-driven mission

Despite his tech focus, Mogensen holds a people-first view of skiing. Yes, hardcore skiers love new lifts and powder and big mountains. But it is the social elements – parties, pond skims, race leagues – that draw the majority of people to the majority of ski areas, especially non-destination community bumps like Antelope Butte, Mogensen says.

This is not just a gut feeling, but a belief built on collecting and analyzing data through Entabeni Systems, whose software is in place at Antelope Butte and many other ski areas. “This was a unique opportunity for me to take years of data and years of trying to think differently, and be able to play with live fire at Antelope Butte and have a board and a community that would support that,” Mogensen said. “We're setting an example and we're tracking it very closely. We have a system in place that your local ropetow is not going to have. We know every visit. We know everyone we sold the pass to. We know exactly how many times they ski. We know exactly what food they buy. We know everything. So at the end of the year, we can do a true regression analysis and see where this made sense and fine-tune the model, but one for the bigger ski area or for the bigger ski area market.”

Not everything that works at Antelope Butte, Mogensen understands, will scale to larger ski areas, or even necessarily translate to a similar ski area in a different region. The point, really, is to build a model that tailors and fine-tunes each ski area’s operations around its observable culture, as translated through data.

“I would really like to show people that it is possible to do something like this,” he said. “It doesn't mean every ski area needs to go do the same thing, and the point here is not necessarily just kids skiing for free. Everyone's mission can be a little different, but the point is being really homed in on the mission, being really good at collecting data and then doing something with it.”

The Storm publishes year-round, and guarantees 100 articles per year. This is article 28/100 in 2024, and number 528 since launching on Oct. 13, 2019.

If you are not aware Howelson Hill a Steamboat Springs city park in operation since 1915 offers free skiing Sunday for all !

Interesting. Even though odds of a powder day would seem to be remote, worth a stop on the way to Red Lodge, Jackson, Targhee… if I am towing the camper.