Who

Jim Quimby, General Manager of Saddleback, Maine

Recorded on

March 6, 2023

About Saddleback

Click here for a mountain stats overview

Owned by: Arctaris Investments

Located in: Rangeley, Maine

Year founded: 1960

Pass affiliations: Indy Pass

Reciprocal partners: None

Closest neighboring ski areas: Sugarloaf (52 minutes), Titcomb (1 hour), Black Mountain of Maine (1 hour, 9 minutes), Spruce Mountain (1 hour, 22 minutes), Baker Mountain (1 hour, 33 minutes), Mt. Abram (1 hour, 36 minutes), Sunday River (1 hour, 41 minutes)

Base elevation: 2,120 feet

Summit elevation: 4,120 feet

Vertical drop: 2,000 feet

Skiable Acres: 600+

Average annual snowfall: 225 inches

Trail count: 68 (23 beginner, 20 intermediate, 18 advanced, 7 expert) + 2 terrain parks

Lift count: 6 (1 high-speed quad, 3 fixed-grip quads, 1 T-bar, 1 carpet)

Why I interviewed him

The best article I’ve ever read on Saddleback came from Bill Donahue, writing for Outside, with the unfortunate dateline of March 9, 2020. That was a few days before the planet shut down to prevent the spread of Covid-19, and just after Arctaris had purchased Saddleback and promised to tug the ski area out of its five-year slumber. Donahue included a long section on Quimby:

But to really register the new hope that’s blossomed in Rangeley, I needed to drive up the winding hill to Saddleback’s lodge and talk to Jimmy Quimby. Fifty-nine years old and weathered, his chin specked with salt-and-pepper stubble, Quimby is the scion of a Saddleback pillar. His father, Doc, poured concrete to build the towers for one of Saddleback’s first lifts in 1963 and later built trails and made snow for the mountain. His mother, Judy, worked in the ski area’s cafeteria for about 15 years. “We were so poor,” Quimby told me, “that we didn’t have a pot to piss in, but I skied every weekend.” Indeed, as a high schooler, Quimby took part in every form of alpine ski competition available—on a single pair of skis. His 163-centimeter Dynastar Easy Riders were both his ballet boards and his giant-slalom guns. They also transported him to mischief. In his teenage years, Quimby was part of a nefarious Saddleback gang, the Rat Pack. “We terrorized the skiing public,” he said. “We built jumps. We skied fast. We made the T-bar swerve so people fell off.”

Just days after his 18th birthday, Quimby left Maine to serve 20 years in the Air Force as an electrical-line repairman and managed, somehow, to spend a good chunk of time near Japan’s storied Hakkoda Ski Resort, where he routinely hucked himself off 35-foot cornices while schussing in blue jeans. When he returned to Maine in 1998, he commenced working at Saddleback and honed such a love for the mountain that, when it closed in 2015, his heart broke. He simply refused to ski after that. “I decided,” he said, “that I just wouldn’t ski anywhere else.” Friends in the industry offered him free tickets at nearby mountains; Quimby demurred and hunkered down at Saddleback, where he remained mountain manager. The Berrys paid him to watch over the nonfunctioning trails and lifts during the long closure. “I’m a prideful person,” he explained. “OK, I did do a little skiing with my grandchildren, but they’re preschoolers. I haven’t made an adult turn since Saddleback closed.”

Quimby is now working for Arctaris, which owns Saddleback Inc., but that’s a technicality. His mission is spiritual, and when I met him in his office, I found that I had stepped into a shrine, a jam-packed Saddleback museum. There were lapel pins, patches, bumper stickers, posters, and also a wooden ski signed in 1960 by about 35 of Saddleback’s progenitors. Quimby’s prize possession, though, is a brass belt buckle he bought in the Saddleback rental shop in the 1970s. “I used to wear it every day,” he told me, “but when Saddleback closed, I put it on a dresser and never wore it again.”

Quimby stood up from the desk now, to reveal that he was wearing the buckle once more. In capitalized brass letters, it read “SKI.” His eyes were glassy with emotion.

“We’re going to do this,” he said quietly, speaking of Saddleback’s resurrection. “We’re going to make this happen.”

They did make this happen. One feature of improbable feats is that they are often taken for granted once achieved. The number of people who confessed doubts to me privately about the viability of Saddleback is significant. It won’t work because… it’s too remote, there are not enough skier visits to spread around Maine, there are too many bodies buried on the property, the previous owners emptied the GDP of a small country onto the property and it still failed. All fair arguments, but for every built thing there are reasons it should have failed. The great advantage of humans over other animals is our ability to solve the unsolvable. I push a button on my phone and a person 5,000 miles away sees a note from me in an instant. That would have been dubbed magic for 100,000 years and now it is a fact of daily existence. Humans can do amazing things. And the humans who dug Saddleback out of the grave did an amazing thing, and it’s a story I just can’t get enough of.

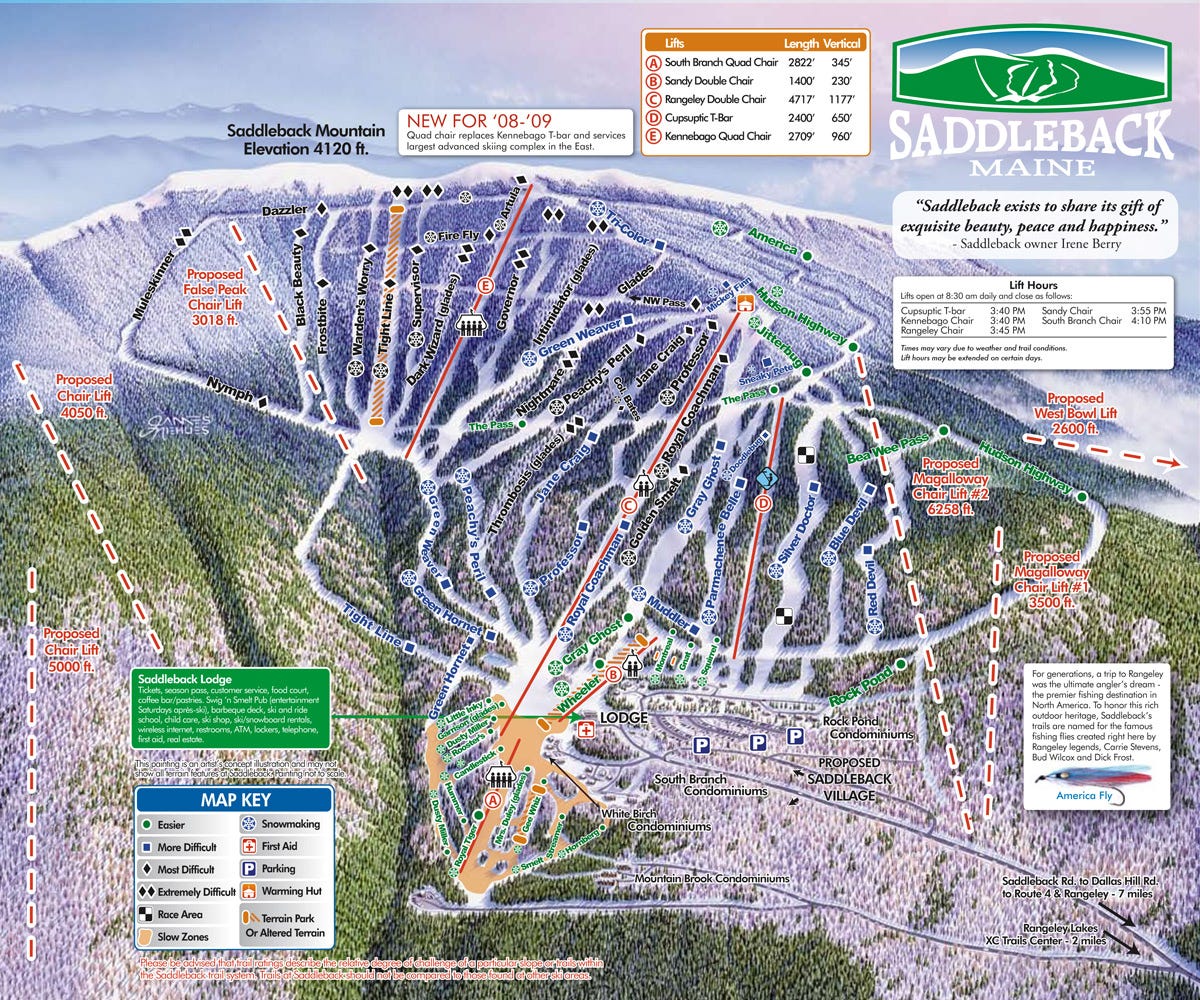

What we talked about

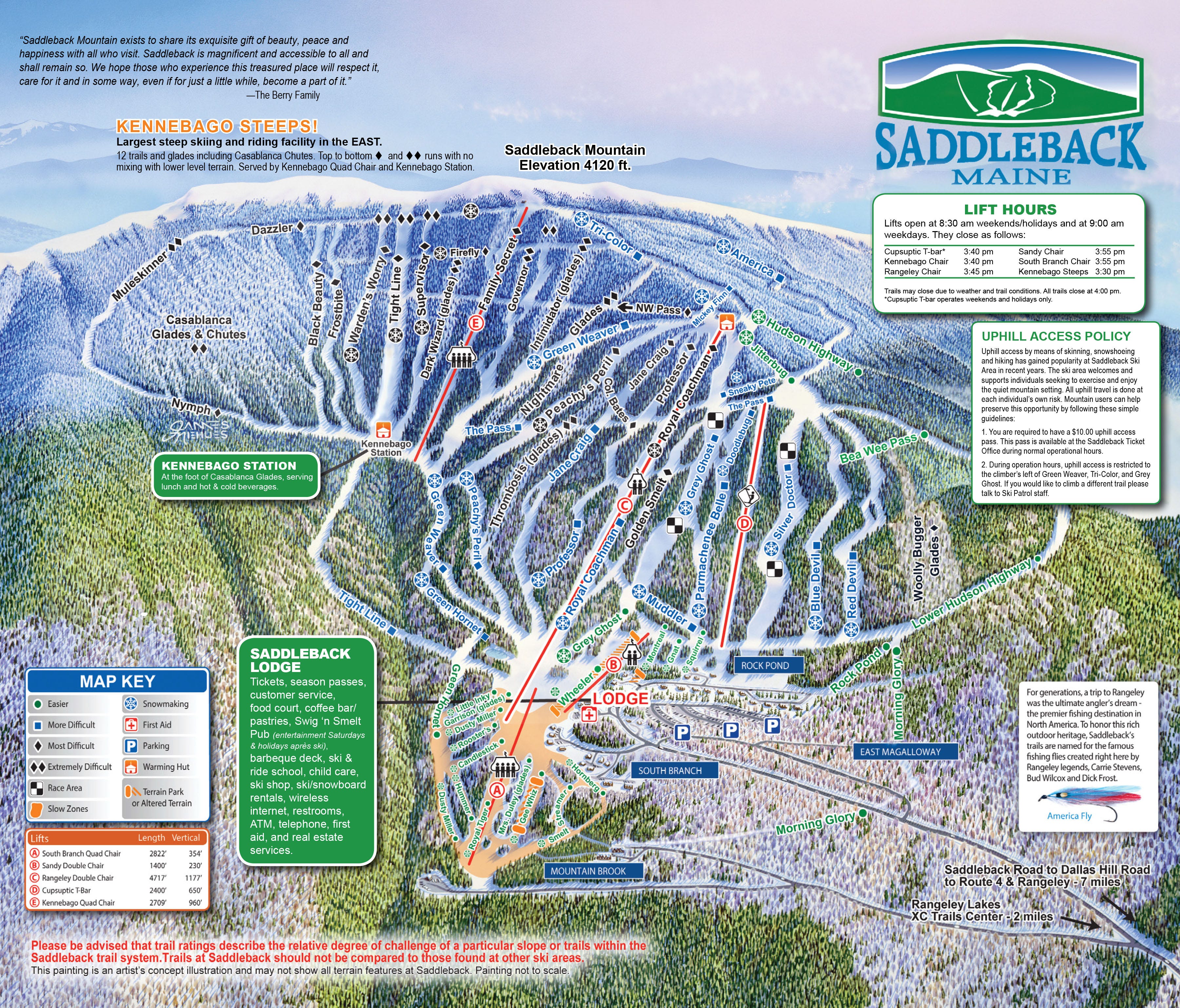

Saddleback’s strong 2022-23 ski season; the Casablanca Glades; the ski area in the sixties; “Saddleback was my babysitter”; Rangeley reminisces; when the U.S. Air Force stations a ski bum in Northern Japan; the Donald Breen era of Saddleback and a long battle with the Forest Service; Saddleback’s relationship with the Forest Service today; the Berry family arrives; an investment spree; why Saddleback closed in 2015; why the Berrys replaced the Kennebago T-bar with a quad and whether they should have upgraded the Rangeley lift first; Quimby’s reaction when Saddleback closed; how Quimby kept Saddleback from falling apart during his five years as caretaker of a lost ski area; why Arctaris finally revitalized the ski area after so many other potential buyers had faded; the most important man at Saddleback; the blessing and the curse of rebuilding a ski area in the pandemic year of 2020; how close Saddleback came to upgrading Rangeley to a fixed-grip, rather than a detachable, quad; how much that lift transformed the ski area; the legacy of Andy Shepard, the former general manager who oversaw the ski area’s comeback; Saddleback the business in year three of its comeback; surveying Saddleback’s ultra-new lift fleet; why Saddleback replaced the 900-year-old Cupsuptic T-bar with a brand-new T-bar; why the ski area chose Partek to build the new Sandy quad and how successful that lift has been; the story behind the old Saddleback trailmaps with theoretical lifts scribbled all over them (yes, this one):

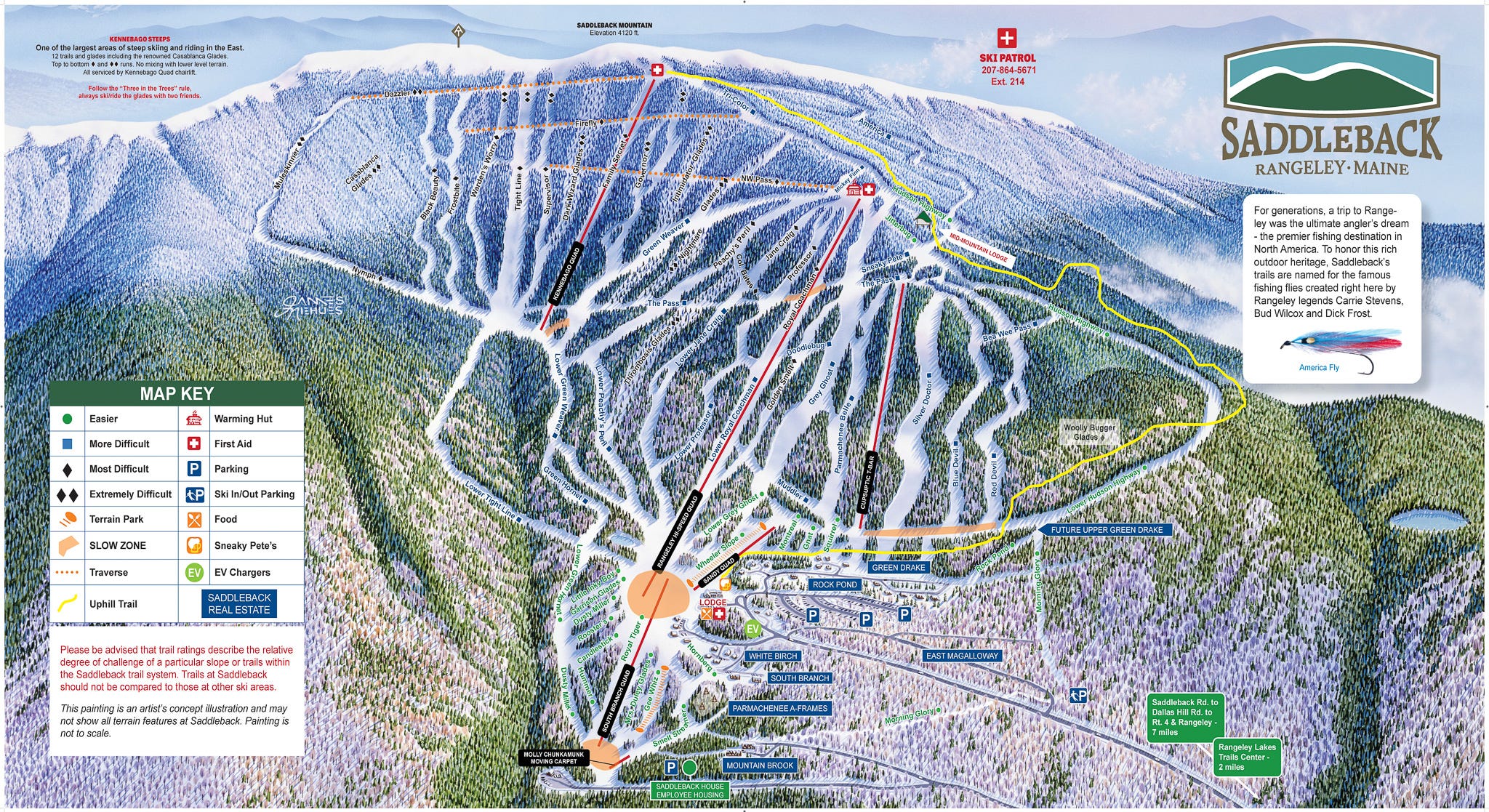

… whether Saddleback will expand terrain any time soon; the ski area’s next likely chairlift; the potential for a hotel; the mountain’s masterplan; how important the Indy Pass has been to Saddleback’s comeback; and Indy blackouts and whether they will continue.

Why I thought that now was a good time for this interview

With lift towers rising up the mountainside and hammers clanging through the valleys and autumn frosts biting the New England hills, Andy Shepard hacked out an hour for me in October 2020 to discuss the previous six months at Saddleback. He itemized the tasks that Saddleback’s crews had achieved in the maw of Covid. An incomprehensible list. Rebuild everything. Clean everything. Hire an army. Demolish and build a chairlift. Stand up a website and an e-commerce platform. All in the midst of the most confusing and contentious time in modern American history. The mission was awesome, and so was the story behind it:

Congratulations, you did it. But the second that new detachable quad started spinning in December 2020, Saddleback became just another New England ski area, just another choice for skiers who already have dozens. So now what? What of all those old masterplans showing terrain expansions and lifts extending halfway to Canada? When can we get more places to stay on the hill? Can we get snowmaking on the trail back to the condos finally?

Two and a half years later, it was time for a check-in. To see how Shepard and Quimby and the crew had quietly transformed what was long a backwater bump into one of the most modern ski areas in the country. To see how the Indy Pass – which hadn’t existed when Saddleback went into its shell – had turbocharged the mountain’s comeback tour. And to see, indeed, what is next for this New England gem.

What I got wrong

I wasn’t wrong on this so much as late to publish: Quimby and I discussed season passes at the end of the podcast. At the time, details on the 2023-24 pass suite had not yet been released, and we talked a bit about where pricing would land. These details have long gone public, but I kept the section intact because Quimby details why the ski area was compelled to raise rates from previous seasons (the increase ended up being modest in the context of ongoing inflation, from $699 this season to $799 for next).

Also there’s a reference in our conversation to Sandy being a detachable quad, but the 227-vertical-foot quad is in fact a fixed-grip lift.

Why you should ski Saddleback

Man is this place big. Two broad ridges staggered and stacked and parallel, with dozens of ways down each. Glades all over. Amazing fall line skiing. Lift lines? Not many. Maybe on Rangeley, maybe on big days. But mostly, the place is a glorious wide-open banger, stuffed into a north country snow pocket that most always stands above New England’s notorious rain-snow line as storms roll through.

“Yes but is it worth the drive?” asks Overthinks Everything Bro. Yes it’s worth the drive. “But I have to pass 19 other big ski areas to get there.” So? If a genie erupts out of my next can of Bang Energy Drink, my first wish will be to eliminate this brand of thinking from existence. Passing other ski areas to ski Saddleback is not like passing a McDonald’s at exit 100 to eat at a McDonald’s at exit 329, more than 200 miles down the road. You’re passing a number of distinct and unique ski areas to experience another distinct and unique ski area. A Saddleback run will imprint on your experience in a way that your 400th day at Waterville Valley will not.

Not all of us, I realize, are so driven by novelty and the unknown. To many of you, turns are turns. Yee-haw. But I’m not suggesting you drive four hours out of your way to lap a town ropetow. This is a serious mountain, with terrain that has few peers in New England. It is special, and it is most definitely worth it.

Podcast Notes

On the ski area’s battle with the National Park Service

Quimby and I had a long discussion on Saddleback’s 15-plus-year war with the National Park Service over former owner Donald Breen’s expansion plans. While Saddleback sits on private land, the Appalachian Trail runs over the mountain’s summit, giving the government a say in any development that may impact the trail. As with most things New England, New England Ski History provides a comprehensive synopsis of what amounts to Saddleback’s lost generation:

With Saddleback finally financially stable and controlling 12,000 acres of land, Breen sought to tap into its vast potential in the mid 1980s. In 1984, Breen told Ski magazine, "Saddleback has the potential to be one of the largest resorts in this part of the country" and could become "the Vail of the East."

While a massive development was possible, including above treeline skiing as well as a bowl on the back side of the mountain, initial plans were made for a phased $36 million expansion "opening up the entire bowl where the ski area sits with three more lifts and numerous trails."

Working to gain approvals, Saddleback offered to donate a 200-foot easement to the National Park Service for the Appalachian Trail while retaining the ability to have skiers and equipment cross the corridor if needed. Countering the ski area's plans, the National Park Service recommended taking 3,000 acres of Saddleback's land. As a result, instead of investing in the mountain, Breen was forced to spend large sums of money to defend his property from eminent domain.

Attempting to break the impasse in the early 1990s, Saddleback offered to pare back expansion plans and sell 2,000 acres to the National Park Service. The National Park Service responded with an offer for one sixth of the amount Saddleback wanted from the property.

By the mid 1990s, Saddleback was offering to donate 300 acres of land to the National Park Service, while retaining the right to cross the Appalachian Trail with connector ski trails. The National Park Service once again refused, sticking with its eminent domain plan. Later Congressional testimony revealed that the Breen family was forced to negotiate with and give concessions to the Appalachian Trail Conference, only to have the agreements retracted by the National Park Service. In addition, the National Park Service would refuse to turn over documents relating to its involvement with other ski areas, or to put parameters of potential agreements in writing.

After having spent a decade and a half of his life trying to work with the Forest Service, Donald Breen took a step back from negotiations in 1997, handing the reins over to his daughter Kitty. The Maine Congressional Delegation was brought in to attempt to get the National Park Service to negotiate.

At Senator Olympia Snowe's urging, Saddleback offered to sell the bowl on the back side of the mountain to the Park Service in exchange for being able to develop its Horn Bowl area. The National Park Service rejected the offer, insisting the expansion was not viable, that the ski area could sustain increased skier visits on its existing footprint, and that Saddleback's undeveloped land had little financial value.

Negotiations continued into 2000, at which point Saddleback had increased its donation offer to 660 acres, while the National Park Service still wanted to take 893 acres by eminent domain. Five proposals were put on the table while the National Park Service threatened to turn the matter over to the Department of Justice for condemnation. Finally, on November 2, 2000, the National Park Service and Saddleback reached a deal in which the Breens donated 570 acres along the Appalachian Trail corridor, while selling the 600 acre back bowl for $4 million. While the deal meant Breen could move forward with his development of the resort, the long battle with the government had consumed millions of dollars and nearly two decades of his life. Now in his 70s, Breen was ready to retire. In 2001, the massive resort property was put on the market for $12 million.

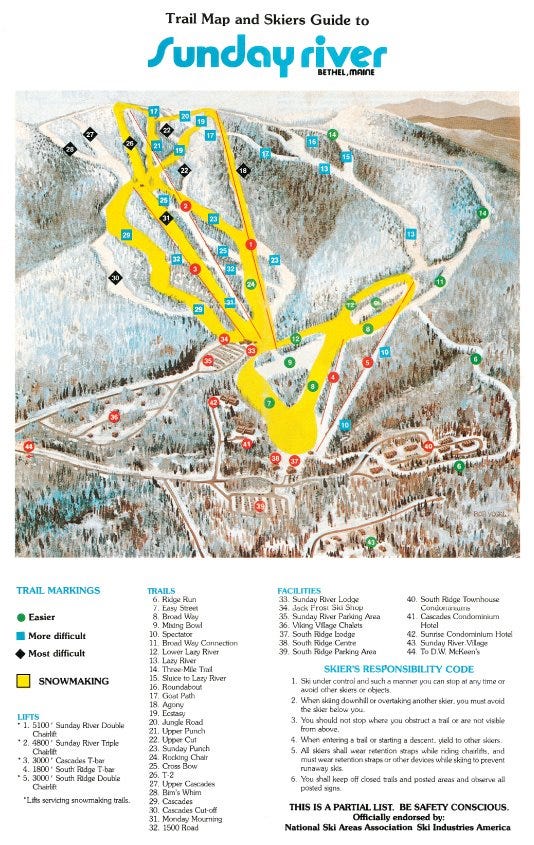

To understand just how deeply this conflict stalled the ski area’s potential evolution, consider this: when Breen and the Forest Service squared off in 1984, Sunday River, less than two hours away and closer to pretty much everyone, looked like this:

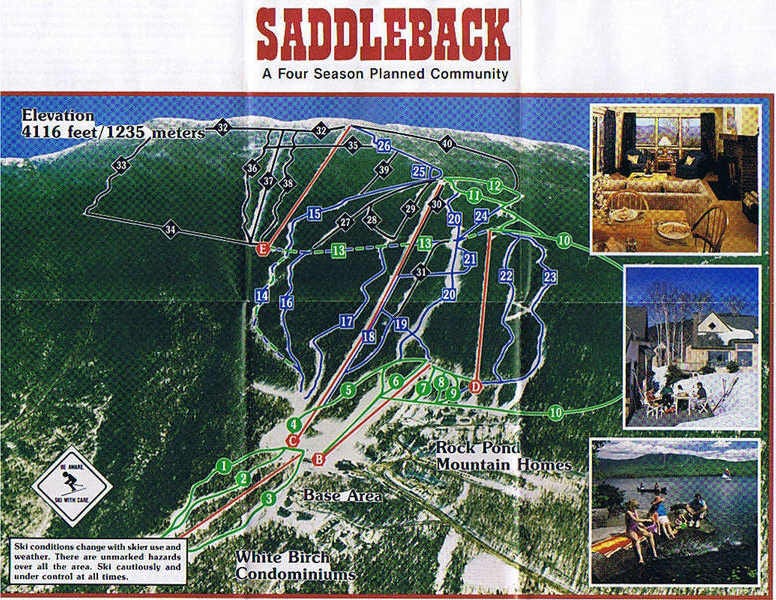

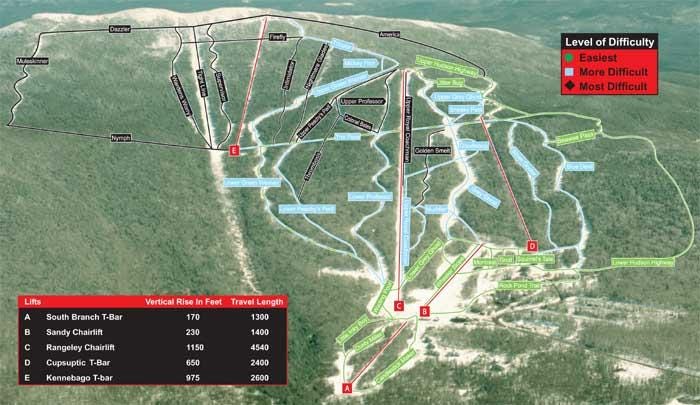

And Saddleback looked like this:

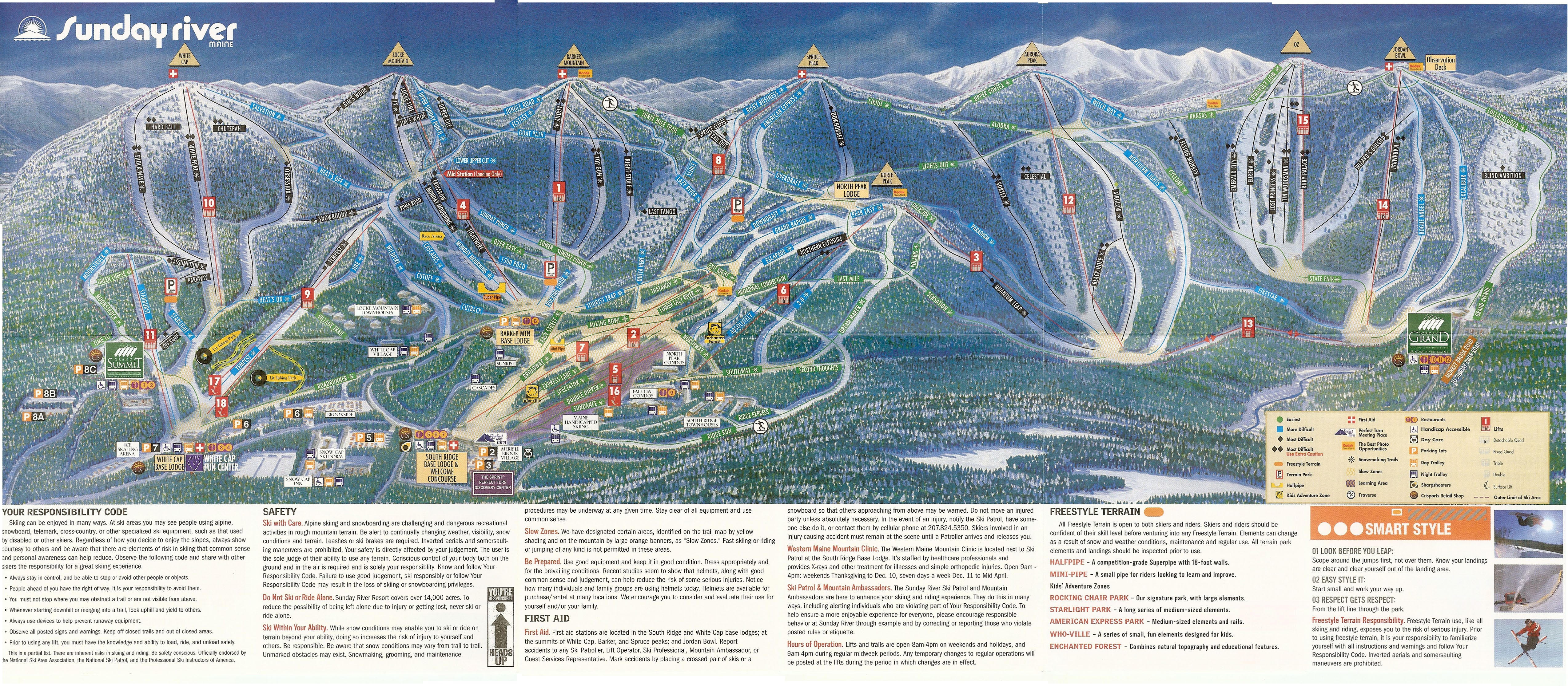

While both had just five lifts – Sunday River sported a triple, two doubles, and two T-bars; Saddleback had two doubles and three T-bars – Saddleback was the larger of the two, with a more interesting and complex trail network. But while Breen fought the Forest Service, his mountain stood still. Meanwhile, Les Otten went ballistic at Sunday River, stringing terrain pods for miles in each direction. By 2001, when Breen sold, Sunday River looked like this:

While Saddleback had languished:

Whatever market share Saddleback could have earned during New England’s Great Ski Area Modernization – which more or less exactly coincided with his Forest Service fight from 1984 to 2001 – was lost to Sunday River and Sugarloaf, both of which spent that era building rather than fighting.

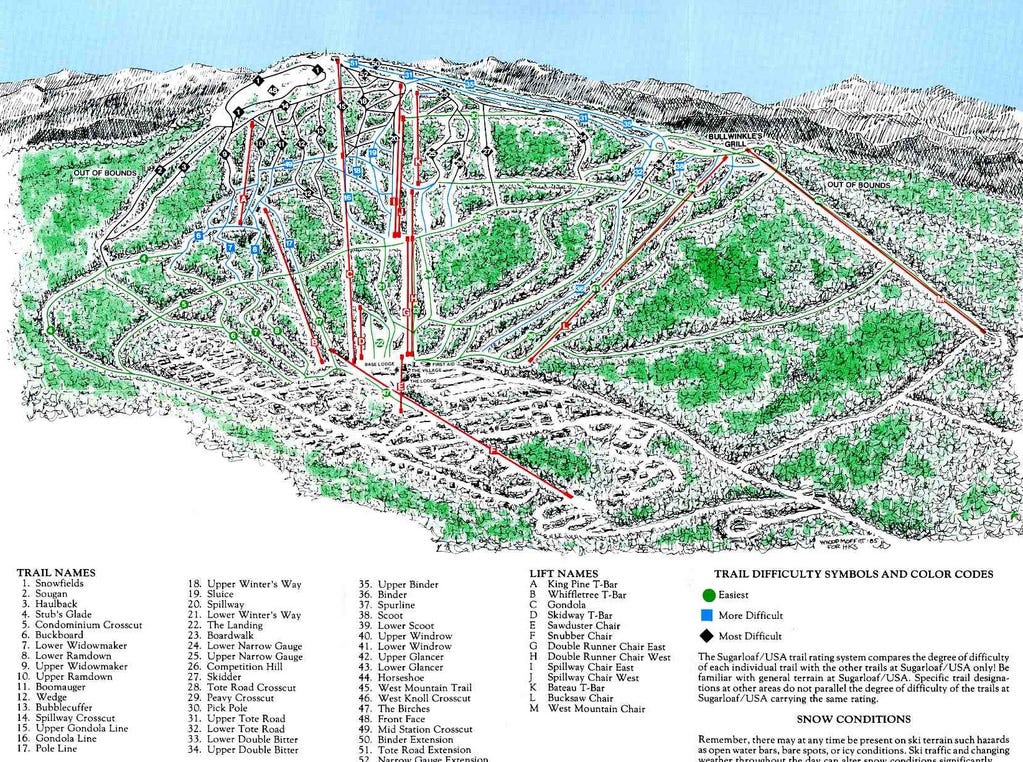

And yes, I also thought, “well what did Sugarloaf look like in 1984 and 2001?” So here you go:

On the Berry family

Breen sold Saddleback in 2001 to the Berry family, who absolutely mainlined cash into the joint. Over the next decade, the family replaced the upper (Kennebago) and lower (Buggy) T-bars with fixed-grip quads, and substantially blew out the trail and glade network. Check the place in 2014:

But two big problems remained. First, that double chair marked “C” on the map above is the Rangeley lift, the alpha chair out of the base. It was a 1963 Mueller that could move all of 900 skiers per hour. And while skiers could have ridden Sandy to the Cupsuptic T-bar (if both were running), to the Pass trail to access the Kennebago quad and the upper mountain, that’s not how most people think. They want to go straight to the top. So they’d wait.

Which leads to the second problem. Queueing up for a double chair that was pulled off of Noah’s Ark when you could be skiing onto high-speed (or at least modern) lifts just down the road at Sunday River or Sugarloaf is frustrating. Lines to board the lift could reportedly stretch to an hour on weekends. Facing such gridlock and frustration, most casual skiers who stumbled onto the place probably thought some version of, “This is cute, but next weekend, I’m going to Sunday River.”

And they did. If the Berrys could have upgraded Rangeley, the whole project may have worked. But financing fell through, as Quimby details in the podcast, and the ski area closed shortly after. But to underscore just how crucial the Rangeley lift is to Saddleback’s viability as a modern resort, Arctaris, the current owners, reportedly paid more to replace the chairlift ($7 million), than they did for the ski area itself ($6.5 million).

On potential buyers between the Berrys and Arctaris

Quimby notes that a parade of suitors tromped through Saddleback between 2015, when the ski area closed, and 2020, when it finally re-opened. The most significant of these was Australia-based Majella Group, whose courtship New England Ski History summarizes:

On June 28, 2017, the Berry family announced they had reached an agreement to sell Saddleback to the Australia-based Majella Group. Grandiose plans were announced, as Majella declared it would be "turning Saddleback into the premier ski resort in North America." Initial plans called for reopening for the 2017-18 season with a new fixed-grip quad replacing the Rangeley Double and a new Cupsuptic T-Bar. However, despite announcements that "physical work" had started in September and that the company was "committed to opening in some capacity for the 2017-18 ski season," the area remained idle that winter and the sale was not completed.

Nearly one year after the original sale announcement, the Majella Group CEO Sebastian Monsour was arrested in Australia for alleged investor fraud, revealing a financial house of cards. The Majella branding was removed from the Saddleback web site that fall and the ski area sat idle during the snowy winter of 2018-19.

So things could have been much worse. Had Majella completed the purchase and then fallen apart, Saddleback would likely still be idle, caught in a Jay Peak-esque vortex of court-led asset salvation, but without the benefit of operating revenue.

On Mount Washington

Quimby notes that the weather at Saddleback can be “comparative to Mount Washington and that’s no joke.” For those of you unfamiliar with just how ferocious Mount Washington weather can be, here’s a synopsis from the Mt. Washington State Park website (emphasis mine):

…in winter, sub-zero temperatures, hurricane-force winds, blowing snow and incredible ice claim the peak, creating an arctic outpost in a temperate climate zone. Known as the Home of the World’s Worst Weather, Mount Washington’s winter conditions rival those of Mount Everest and the Polar regions.

The mountain’s summit holds the world record for the “highest surface wind speed ever observed by man,” at 231 miles per hour. As I write this, the summit temperature is 4 degrees Fahrenheit, with 62-mile-per-hour winds driving the windchill to 28 degrees below zero. It’s April 2.

There’s surely some hyperbole in Quimby’s statement, but the spirit of the declaration is clear: if you go to Saddleback, go prepared.

The Storm publishes year-round, and guarantees 100 articles per year. This is article 30/100 in 2023, and number 416 since launching on Oct. 13, 2019. Want to send feedback? Reply to this email and I will answer (unless you sound insane, or, more likely, I just get busy). You can also email skiing@substack.com.

Podcast #121: Saddleback General Manager Jim Quimby