Ode to the Ticket Wicket

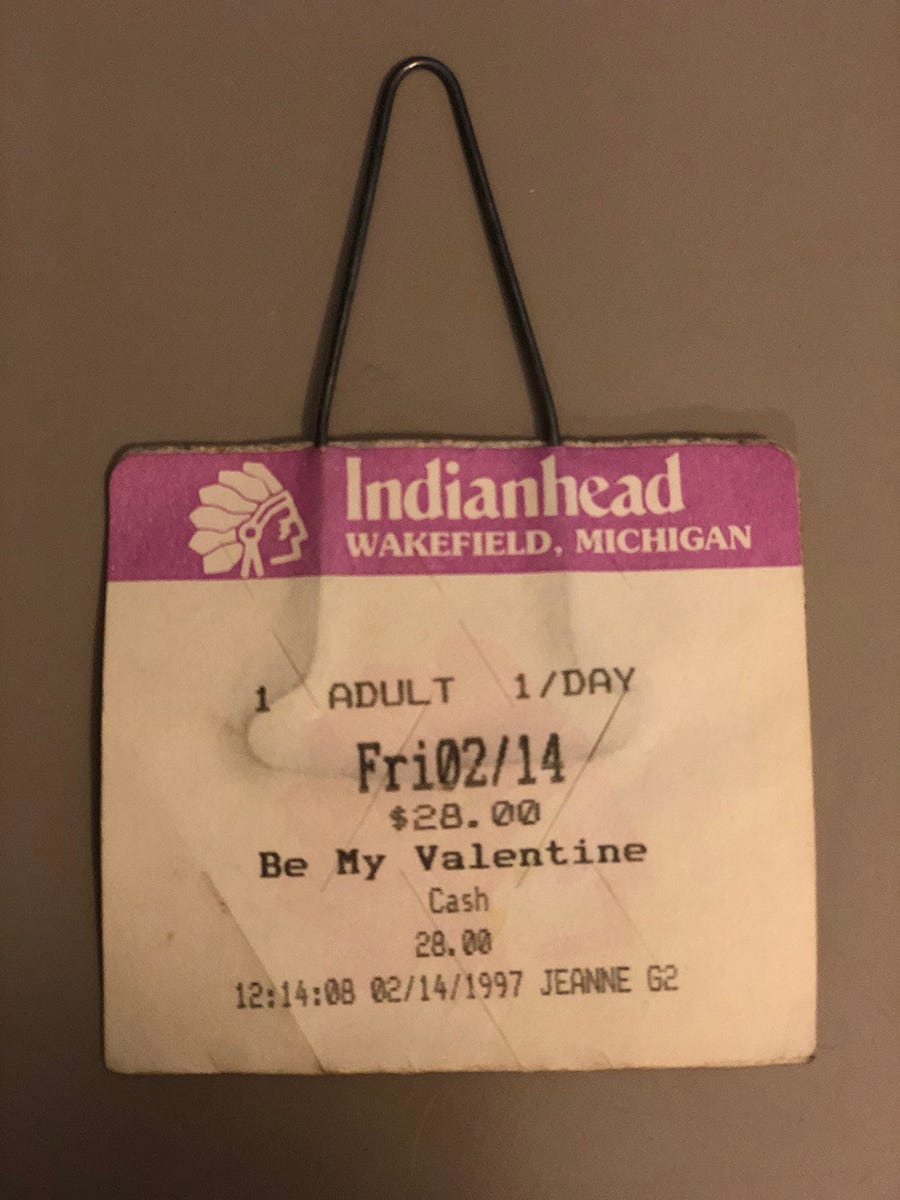

There’s a box in my basement, hinged and wooden and flip-topped. It sits on top of a book shelf, stacked among similar boxes, some plain and some decorous, that together warehouse the ticket stubs to every concert, baseball game, Broadway show, theme park and movie I’ve attended since I was 8 years old. There are three or four of these other boxes, their contents mostly disordered, shuffled, random, a ticket to a 1985 Detroit Tigers game atop a movie stub from Jurassic Park’s June 1993 opening day atop a ticket to a 2001 Chicago Cubs game at Wrigley Field. But there is nothing random about the contents of this steel-hinged box. Only one kind of thing lives inside: my lift tickets.

The oldest among them lay bunched along key rings that had once been hooked through the zipper of a long-discarded Spyder jacked, humped and rusting wickets curling one after the next in perfect symmetry over the steel ring before funneling into the creased and many-shaped and mottled jostle of folded lift tickets. Each of these clusters memorializes a season, like tree rings documenting the long-fallen rains, communicating a fat or lean year, a record not so much of the weather as of my dedication to getting out into it.

Ordered, still, in the sequence I slid them on decades ago, the tickets on each keyring constitute a travelogue and a historical flip book, a time machine that is in most cases the only tangible relic I have of any given day on skis.

Some are date-stamped and some are not. A few have barcodes, and the number that do increases as the years advance. Many have the price stamped on them, though their current dollar value is universally zero. Some carry artwork of skiers and mountains that looked antiquated even in the ‘90s.

Repeating zigzag patterns zip across others, the florescent neoprint design schemes of 1980s streetwear and album covers transposed in its meaningless squiggles and angled lines.

There too are historical oddities and outmoded business models, like the three one-day lift tickets that copper Mountain issued me for a three-day trip over the New Year’s holiday as 1995 turned to ’96 (I have no idea why the hotel gave me, an 18-year-old college freshman, tickets stamped in association with the Oklahoma Physicians Association).

There are relics of a snowier past, of long-shuttered ski areas sustained at one point without snowmaking, like Skyline outside of Grayling Michigan, and scraps of forgotten bumps, town hills like the hills we all started on. Mott Mountain and Apple Mountain, both in Central Michigan, and Nebraski, lodged improbably between Omaha and Lincoln off Interstate 80.

I don’t know why I started saving them, other than that I have always been a collector and have always hoarded anything tangible as a way to grasp onto the ephemeral. But once I began saving them, their condition became important to me. I developed a meticulous process of folding and peeling and refolding in order to transfer the ticket uncreased and symmetrical from its sticky back to the wicket. After snipping the wickets with wire cutters after a first early ‘90s season, I developed the keyring method, to keep the tickets hooked neatly for eternity in their keyring scrapbook. I would watch in horror as my friends would tear the ticket up the center to remove it along with its bent and mangled wicket, or paper them one over the next like a lazy handyman dropping linoleum over older linoleum over hardwood.

In that time when my ski coat was my only coat – when the idea that a person would simultaneously own more than one of something so expensive as a winter coat, and each for different purposes, seemed bizarre and outrageous to me – I would wear these wickets proudly. As winter wore on and these tokens multiplied like a grown thing I carried them like merit badges, each a thing accomplished – a day of skiing – that was symbolically conjured for adoration by these dangling mementoes. Like a sports fanatic outfitting himself at all times with regalia that marks him as a fan of his favorite team, I strolled cocksure and smug in my plumage, broadcasting to the world that a skier – a frequent, fanatical skier – walked among them.

The skinny skis! The rad haircut! The bunched lift tickets exploding off the jacket zipper! Don’t “where’s that kid’s helmet?” me, Mister - this was the ‘90s. Your author at Searchmont, Ontario in 1996.

As the years progress in the geological layers of my humble box, the knots of ring-bound wickets grow thinner. It is not, necessarily, because I began skiing less, though some lean years indeed came. Partly this is because those charmless plastic wickets that began proliferating in the early 2000s defy the neat symmetry of stacked wickets and splay outward in an unruly mass, like dropped playing cards. These I cut off and discard at season’s end, flattening the ticket beneath a heavy book for some weeks before entombing them within the box.

Rather, the stacks grew thinner through the years because the lift ticket is dying. Everybody knows this. RFID cards, tucked in coat pockets and proliferating for years, have rendered them obsolete. I skied thirty-eight days last season and collected thirteen lift tickets, only five of which dangle from metal wickets. The rest are lost in the RFID ephemera. Another five – four from Belleayre, one from Gore – mark the last call of their kind, as both switch this season to gated lift access.

Of those five classic wickets, four came from a long weekend ski trip to Michigan in January (the fifth came from that ultimate vault of the old school, Mad River Glen; just imagine a RFID gate arched over the entryway to the single chair).

I had not skied Michigan in years. I had assumed that the state – a frozen and snowy place as passionate about the sport as any – had joined the rest of the ski world in its technological migration. How delightful, then, to arrive at Caberfae on that zero-degree Saturday and be handed a geometric color-block lift ticket that was a slightly updated version of its 1990s ancestors entombed in my Brooklyn basement.

A 1995 Caberfae lift ticket on the left, the 2019 version on the right.

Even my friend, a Caberfae season ticketholder, had to present her pass in exchange for a fresh wicket setup. In the liftlines, you could spot the hardcore skiers, their jackets dripping with dozens of tickets, dangling off multiple zippers in neat bundles, their volume and variety wordlessly telegraphing a kind of status, the snowy equivalent of military ranks and history as communicated through the placement and volume of medals and epaulets.

I am aware that this is a stupid thing to care about. Even if individual lift tickets eventually disappear altogether – and I think that’s unlikely, given the prohibitive costs of RFID to smaller independent areas – that will have no correlation with our ability to continue skiing, just as the volume of The New York Times sitting on the newstand has little to do with the publication’s success and reach. Anyway, our sport faces far greater existential dangers than the loss of this tangible souvenir.

But I care about it anyway. I am old enough to have lived into early adulthood without ever using the internet. I well remember the analogue world of artifacts that came before it, and I am sad to see that world fade. I mean, I get it. The ticket is extraneous now. We have other ways to document our experiences. My Slopes ski tracker app records the granularia of my days – every run, every lift, every stop, the velocity and clock time associated with every one of those things. I take more pictures and videos by noon on my average ski day than I snapped during the entire decade of the 1990s.

But these digital artifacts, complete as they are, and as permanent as they theoretically are, feel disembodied. There is no direct connection between you and the resort, no token handed over to you as part of the financial transaction, no slice of art transmitting something about the mountain’s attitude or essence or place in time. There is nothing to take with you or grab onto, to look down at a month later from another chairlift on another mountain, to cut off at the end of the season and stack in a box, where you may look at it a year later or twenty years later or never again.

I have to admit that I am bashful about this box. I am entirely aware of how ridiculous this collection appears to most people. The number of lift tickets that most serious skiers retain is exactly zero. Who cares what you were doing on March 11, 1996 (skiing Searchmont, Ontario)? How many times you skied there that season (four)?

It’s a fair question, but an easy one: because I do. And I always have. And I don’t understand those people who don’t have some kind of interest in their own history, who don’t take pictures or save anything or remember if that sick powder day at Jay Peak was three years ago or eight.

But more people are like that than not, and in the majority-rules market economy in which the North American ski industry operates, that means that the long decline of the lift ticket is only likely to accelerate. That’s fine. Like a buggy master at the dawn of the automotive age, I’ll enjoy this horse ride for as long as it lasts, even as more and more of my own journeys are in a Model T.

The Storm Skiing Podcast is on iTunes, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, TuneIn, and Pocket Casts. The Storm Skiing Journal publishes podcasts and other editorial content throughout the ski season. To receive new posts as soon as they are published, sign up for The Storm Skiing Journal Newsletter at skiing.substack.com. Follow The Storm Skiing Journal on Facebook and Twitter.

Check out previous podcasts: Killington GM Mike Solimano | Plattekill owners Danielle and Laszlo Vajtay| New England Lost Ski Areas Project Founder Jeremy Davis | Magic Mountain President Geoff Hatheway

Another article I totally agree with and I do the same thing with all my lift tickets. Glad there are more than one of us.

Love seeing the old wickets. I have almost every wicket I every bought. Not that many, but as a longtime passholder (Gore and Plattekill), most of my wicket days were excellent days.