If The Little Cottonwood Gondola Was Powered By Kittens and Coal, the Anger Still Wouldn’t Make Sense

Advocacy groups move to delay LCC Gondola construction with lawsuits.

We wouldn’t want a gondola to ruin the view of that beautiful highway

Opposition to the proposed gondola up Little Cottonwood Canyon has always hit me as a little bit stupid, particularly when it’s framed as some great mission to save the environment. Check out this excerpt from a recent lawsuit filed against UDOT to stop construction, per The Salt Lake Tribune:

Among other claims, the lawsuit [to throw out UDOT’s environmental study as flawed] says the proposed gondola through the canyon would, “affect the natural habitats of golden eagles and other fauna; contaminate and endanger a critical watershed; disrupt recreation areas unrelated to resort skiing such as climbing, hiking, and backcountry skiing; and permanently alter the breathtaking views of the canyon.”

You know what the most disruptive thing you can possibly build into the wilderness is? A paved road. You know what permanently altered the view of that breathtaking canyon? State Route 210, the road punched through its gut in the 1940s. What do you suppose has a higher chance of “contaminating and endangering a critical watershed” – thousands of individual oil-leaking, exhaust-spewing vehicles, or a gondola with 22 towers that each occupy a few hundred square feet of land?

Anyone who’s serious about protecting the environmental integrity of LCC ought to be advocating that they close SR-210 permanently and replace it with low-energy, low-impact alternatives such as the gondola and, perhaps, a train. The road could remain open to emergency vehicles and, perhaps, residents.

When protesters are not complaining about imaginary environmental impacts, they are complaining about the lift’s price, ignoring the astronomical expense of road maintenance and avalanche mitigation. The gondola will cost an estimated $728 million, which sounds like a lot until you realize that mountain roads cost more than $4 million per lane, per mile to build – and that’s in 2014 dollars. There’s also the cost to the individual of purchasing and outfitting vehicles that can manage extreme winter weather on steep terrain – the gondola would mostly negate the need for such Monster Truck One-Upmanship, as it would move the resorts’ base down to around 5,000 feet (from 7,760 feet at Snowbird and 8,530 feet at Alta), below the major snowline.

A UDOT spokesman told The Tribune that the lawsuit may delay implementation of so-called Phase 1 elements of the LCC traffic-control plan, including tolling and increased bus service, while the agency prioritizes resources. The plan appears to be to deploy the Early Winters strategy, which stopped a potential Washington ski resort with a philosophy of petty nitpicking. Per Methow Valley News:

“The first realization was that we would be empowered by understanding the rules of the game.” Coon said. Soon after it was formed, [Methow Valley Citizens Council, MVCC] “scraped together a few dollars to hire a consultant,” who showed them that Aspen Corp. would have to obtain many permits for the ski resort, but MVCC would only have to prevail on defeating one.

Administrative and legal challenges delayed the project for 25 years, “ultimately paving the way to victory,” with the water rights issue as the final obstacle to resort development, Coon said.

That article is from 2016. These activists are still so proud of themselves, decades after killing Early Winters. But what did they achieve, besides stopping something that could have been transformative for the entire region? What could have been an extra ski resort in a state that desperately needs more skier capacity is instead “open space” that is zoned for the development of exactly five homes.

This is what’s happening in Utah. A band of reflexive nimrods, brainwashed on the U.S. American imperative to spend unhealthy percentages of their income on personal vehicles tricked out with military-grade terrain-scaling features, recasts the most obvious fix to the traffic and visual clutter that mars one of America’s most gorgeous canyons as an engine that would instead destroy it. This is one of those things, like Americans’ obsession with air-conditioning or ketchup, that looks absurd with even a little distance. Little Cottonwood Canyon was never meant to accommodate thousands of vehicles per day. It was never meant to accommodate vehicles at all. SR-210 holds the highest avalanche hazard index of any road in North America. Removing personal cars from that road is such an obvious solution that it rates alongside toothpaste application as Things That Shouldn’t Have to Be Explained.

But the fight will go on, until one side or the other breaks. And I doubt that will be anytime soon.

While you’re in Park City, don’t bother skiing Park City

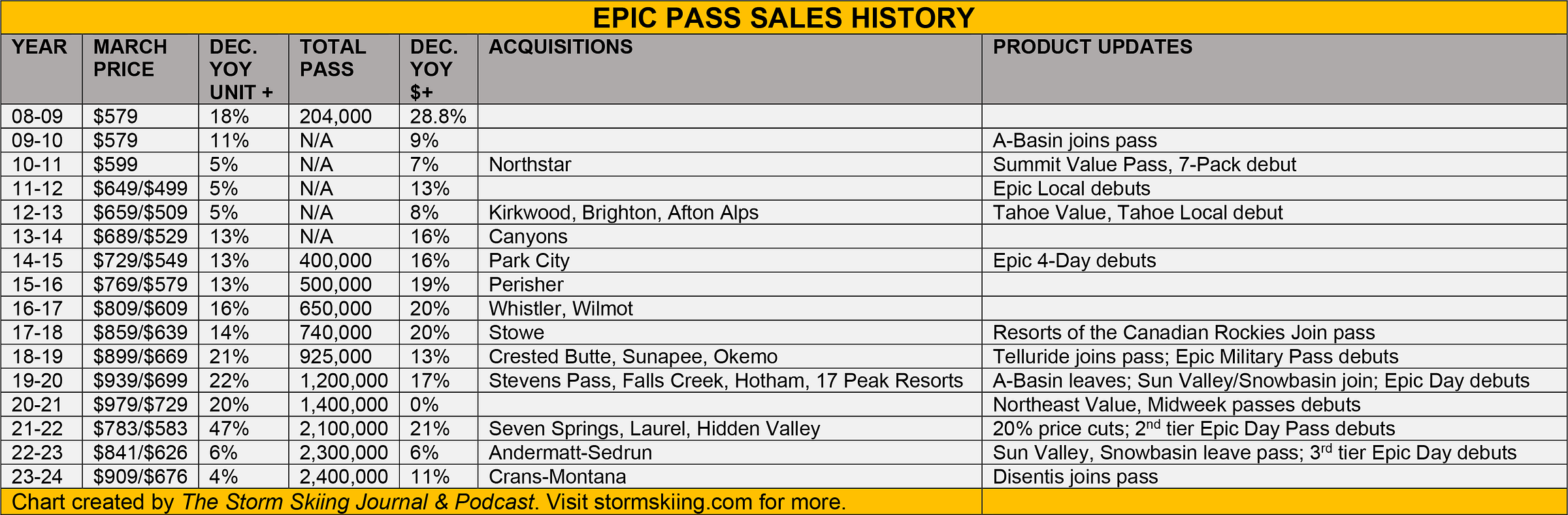

In October, Vail quietly terminated Chief Marketing Officer Ryan Bennett. While we can’t assume plateauing Epic Pass sales led directly to the separation, last week’s earnings release suggest the company’s hyper-growth days are over. Epic Pass sales increased just four percent in units sold (the lowest increase on record), and 11 percent in sales dollars year-over-year, with 2.4 million total pass products sold – only 100,000 more than 2022. Here’s a look at year-over-year Epic Pass sales since the product debuted in 2008:

It looks as though just about everyone who intends to buy an Epic Pass is buying an Epic Pass, and Vail is running out of people who don’t intend to buy one but should buy one. The mountains aren’t getting any bigger (one-off expansions accepted), and winter isn’t getting any longer. Vail hasn’t purchased a new U.S. ski area in two years. It’s the Netflix problem on snow – when just about everyone who is likely to subscribe to your service subscribes to your service, how do you continue to grow?

Vail, like Netflix, has been swiveling its binoculars overseas. As with a content creation company, Vail is going to hit some cultural obstacles. Just as what’s funny to Americans doesn’t always land in Italy, America’s roughneck version of skiing doesn’t always appeal to Euros, who ski with an espresso in one hand and a newspaper in the other, leisurely reading as they skate down the piste.

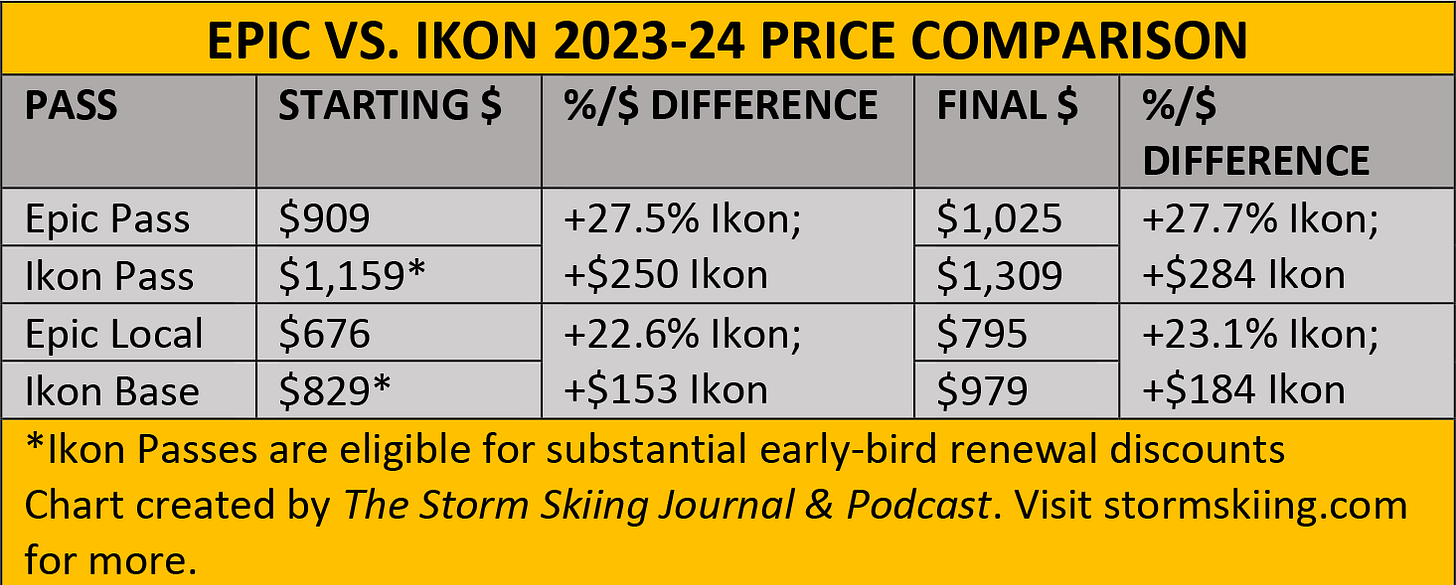

So how does Vail re-ignite growth? Strategic pickups in so-far neglected markets – the Southwest, Upper Rockies, and Southeast – is one way to go, albeit an expensive one. Vail can continue to buy in Europe, but I’m not sold on the Epic Pass scaling in Europe barring an explosive critical mass of acquisitions on the continent. The path of least resistance here is to raise prices. Even a material increase would leave a considerable gap between Epic and Ikon rates. Check the differential between Epic and Ikon early-bird and final 2023-24 prices:

Ikon can somewhat justify that premium with a beefier lineup that includes 32 western North American destinations to Epic’s 11. But Ski Tourist Bro isn’t going to need 32 choices. Vail Mountain and Park City and Heavenly are just as good as Copper and Deer Valley and Palisades Tahoe from an average skier’s point of view. The Epic Pass could be more expensive, and it probably should be.

Vail’s in a weird place where it needs to consider both lowering and raising prices. Skiers have been retrained to buy their passes six months before they ski – they’re going to keep doing that even if prices tick up 10 or 15 percent. The Epic Pass would still be a bargain at $1,200. Day tickets, on the other hand, look as though they’re being managed by the same people who set over-the-counter prescription drug prices. $750 for one antiparasitic Daraprim pill that cost $13.50 last week? What an innovative business strategy. $299 for a lift ticket that, adjusted for inflation based upon 2007 (pre-Epic Pass) rates, ought to sell for around $137? Man, Vail must be lined up on the steps of Harvard Business School on graduation day to capture these brilliant minds.

An acquaintance texted me today to tell me he was on his way to Park City with his girlfriend, and he’d come across my recent podcast interview with VP/COO Deirdra Walsh. We hadn’t spoken in a number of years, and he was congratulating me on the platform. He would not, however, be skiing on his trip to Park City. “The pricing is wild,” he said. Indeed: $237 to ski this Friday ($249 at the window); $255 for Saturday ($269 at the window). Go next door for lift tickets? Ha. Deer Valley lift tickets run $259 per day this Friday and Saturday. I told him to check out Sundance ($129 per day), or Nordic Valley (currently $43 online for Friday and $55 for Saturday).

This is not, by the way, some broke-ass buddy who crawls out of the bottle to beg for a couch every three years, but a dude with a solid job and the ability and desire to travel. But here we are, in December 2023: when someone asks me where they should ski on their ski trip to one of America’s great ski towns, home to two of America’s greatest ski resorts, I tell them to go ski somewhere else. Make that make sense.