Here’s How My Ski Season Ended

And how the good people of Maine came to my rescue

The first time is never the first impression. Not really. By the time I swing the van into the parking lot and boot up in the backseat with the engine running and drop hand warmers into each glove and stand at the passenger-side sliding door wrestling my skis out of the Thule box, I’ve done all the scouting. Studied trailmaps past and present. Compared them to satellite view on Google Maps. Noted the age, size, and capacity of the lift fleet. The mountain’s proximity to other resorts, borders, major highways or landmarks. It’s all part of my process and I love the process.

In the East, most ski areas surprise you. A few – Killington, Hunter, Whiteface – rise like snowy kingdoms over their approach roads. But most, even the big ones, hide. Mad River Glen blows 2,000 feet into the sky and sometimes it’s hard to see from the parking lot. Typically: The GPS indicates you’re a half mile away and yet, no sign of skiing. Sometimes you’re in a neighborhood and sometimes you’re on a straightline backroad and sometimes you’re riding through one of those Northeast smalltowns cobbled together with the Lego blocks of dispersed centuries, a big-windowed brick saloon here and a Cape Codder there and a Sunoco/Dunkin’ Donuts at the end of the strip. But always, eventually, there’s skiing, right where the robot promised it would be.

Always a rush when at last I see it. Like some reverse Amazon, delivering myself to the goods. A fantasy, actualized. I am addicted to this. To novelty and discovery and variety and newness. To the thousands of versions of the same thing that is the worldwide tapestry of lift-served skiing. Twenty-two times this season I repeated the process: Pico and Attitash and Pats Peak and Sunapee and McIntyre and Butternut and Otis Ridge and Woods Valley and Bristol and Sawmill and Smugglers’ Notch and Holiday Valley and Cockaigne and Peek’n Peak and Mount Pleasant and Tussey and Wachusett and Nashoba Valley and Ski Ward and Cranmore and Shawnee Peak.

And on Friday, February 11, Black Mountain of Maine.

Sunshine and surprise snow

I skied with the Angry Beavers, of course. There is nothing else quite like them in New England. There may be nothing else quite like them anywhere. In the past decade they have done a thing the non-profit ski area itself could not have: drilled an expansive network of glades into the mountainside. They did it for free and they did it for love and they did it because it feels good to sculpt a mountain and they did it for the addiction to challenge and dynamic movement and puzzle-solving that unites all tree-skiers.

They are artists, their work glorious. For the pitch, you can thank the mountain, their canvas. But the rest – the spacing, the line choice, the absence of poke-through-the-snow obstacles, the sheer volume – is all thanks to the Beavers. Their paintbrush a chainsaw, their paint skiers gliding through the snowy woods.

I’d intended to ski Seven Springs on this day. Then Suicide Six. As the refreeze line moved north, so did my plans. Black had gotten two feet in the previous week. The trees would be live. Settled, I turned north. But I didn’t beat the refreeze. The day before at Cranmore I fought for turns in plated snow, crusty layers echoing through the forest. Like I was skiing across gravel or cinderblocks.

But on Black Mountain – a surprise. Two inches overnight. Booting up in the high-ceilinged lodge – buffed and balconied and unexpected in a place so pridefully retro – the overnight groomer, Jeff Knight, swaggered in. He was grinning and insistent in his Carhartt: “Better get up there. It’s nice.”

I skied with a group of locals - George and Elana and Jerry Marcoux, father of Angry Beaver leader Jeff Marcoux - and Deanna Kersey, the mountain’s marketing manager. Together we rode the lift and skied the groomers and paused at Lunch Rock and they pointed at things and told stories about them. But Michael Hogan was there to show me the trees:

All day in the glades. The snow morphing with the aspect, the light and the shade. The sun high like a sentry. Forty degrees by noon. The mountain faces east, with a slight tilt south. The snow grew heavy in the untracked trees skier’s left. We kept skiing. The triple chair rises 1,140 feet and there’s another 200 feet to hike but we never did. In the trees 1,140 feels like 2,000. The runs neverending.

Run 460

On my final run of the season we swung skier’s right off the lift, seeking shade, tracked-out snow for easier turns. We found them in Crooked glade. Emerged on black-diamond Penobscot. Ungroomed. Snow heavy in the sunshine. A little sticky. As though someone had caulked the hillside. Try this or more glades? Let’s try this. It was my 13th run of the day. My 460th of the season. It was 1:22 p.m. I let my skis run. Gained speed. Initiated turns. I was leaning into a right turn at 18.9 miles per hour when I lost it.

I don’t really know what happened. How I lost control. I know what didn’t happen: the binding on my left ski – 12-year-old Rossies I’d bought on spring clearance at Killington – did not release. Amazing pain in my leg. My body folded over backwards, bounced off the snow. A rattling through the shoulder where I’d had rotator cuff surgery last summer. I spun, self-arrested. Came to a stop on a steep section of trail, laying on my left side, my leg pinned into bent-knee position.

I screamed. The pain. I could not get the ski off. I screamed again. Removed my helmet. Let it drop. It spun down the hill. Adrenaline kicked in. A skier appeared. He helped me take my ski off. DIN only at 8.5 but the binding was frozen. Finally it released. I tried to straighten my leg. Couldn’t. I assumed it was my knee. Isn’t it always a knee? More skiers arrived. Are you OK? No, I’m in a lot of pain. They left to get help. Patrol arrived with snowmobiles and sleds and bags of supplies. Michael came walking back up the hill.

Everything after, rapid but in slow-motion. Does that make sense? Gingerly onto the sled, then the stretcher, then the Patrol-shack table. EMTs waiting. Amazing drugs incoming. Off, with scissors, my ski pants. Removing the boot, pain distilled. Not your knee – your leg. Broken bones. Did not penetrate the skin. Into the ambulance. Rumford Hospital: X-rays and more pain meds mainlined. A bed in the hallway. From the next room a woman, emphatic, that she don’t need no Covid vaccine in her body. All night there. The staff amazing. I would need surgery but there were no surgeons available until the next day. A room opened and they wheeled me in. In a druggy haze they splinted my leg. A train of drunks and incoherents as the bars emptied out. Sleep impossible.

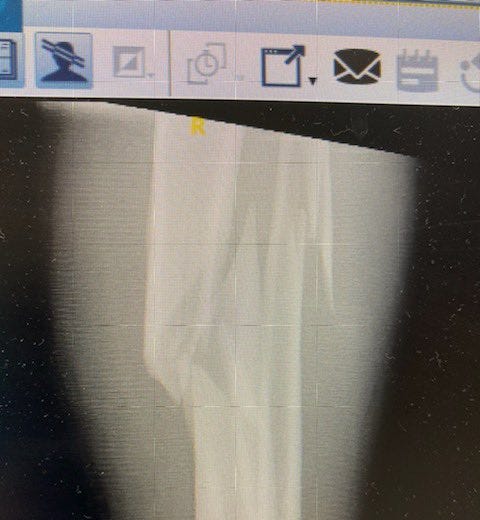

The next morning a long ambulance ride to Central Maine Medical in Lewiston. There a surgeon, a skier himself, amazed by my break – tibia and fibula. “Spectacular,” he called it. “You have strong bones. They resisted the break. When they broke, they exploded.” A spiral fracture splintering into what he called butterfly fragments. “Normally those are three or four millimeters long. Yours were 20. Just amazing.”

Surgery happened in an instant. At least for me, drugged and grateful to be a citizen of the future, of this amazing century with this impossible technology. Here is what he fixed:

And then. What a mess I was in. Alone in Maine. No way I could drive. My car 45 miles away anyhow.

But you’re never alone in Maine. My God, that state. The people. The Patrol, fast, efficient, empathetic as I screamed. EMTs waiting at the bottom. Hogan, at Black Mountain, gathering my poles and skis and helmet and boot bag and trashed pants and stuffing them in my van and driving it to a fellow Beaver’s home, across the street from Rumford Hospital. Everyone at the mountain offering to help in any way they could.

I’d asked enough of them for one day. I emailed Dana Bullen, president of Sunday River, half an hour from Black, for advice. Instead of telling me what to do, he did everything. I will not go into the extent of what Sunday River did to get me and my vehicle back to Brooklyn, but I will say that the entire episode is exhibit A for the value of experienced leadership at ski resorts, of valuing these people more than the $5 million lifts that cart your skiers up the mountain. If your first move when you buy a new resort is to cut off its head, you are making a mistake. Bullen is one of the most well-connected and well-respected people in the entire state. He is a problem-solver. Like watching a child savant destroying a Rubik’s Cube, it is impossible to understand what’s going on even as you observe it. One day you are in Maine contemplating the end of your ski season and the next day you are on your couch in New York and even then you’re not quite sure how it happened. But it did, and I will always be grateful to Bullen and his team for that.

My wife flew up from New York the day of the surgery. She was not allowed in the hospital, but we spent Saturday watching movies in a Hampton Inn and eating enormous bags of food from the Fishbones across the street. And the next day a long journey home.

What I lost and what I gained

As I lay on the snow waiting for Ski Patrol, my season began clicking away in my head. I had trips planned. King Pine, Waterville Valley, Black Mountain (New Hampshire), Palisades Tahoe, Northstar, Heavenly, Kirkwood, Diamond Peak, Big Sky, Bridger Bowl. Many others. Not this year. I knew that before I even understood what had happened.

I’ve spent the last week on my couch. Sitting up for any length of time is painful. The leg must be elevated. I am very fortunate that I can still work. I take Zoom calls in my hoodie, pained glass of my street-level windows behind me. That’s not unusual – my last day in the office was March 12, 2020. But this is not my normal Zoom background. People ask about it. I tell them.

My ski season is over. I’m OK with that. Twenty-seven days, 34 ski areas, 460 runs, 332,000 vertical feet. Not bad for a guy who lives in Brooklyn. I miss it of course. Miss skiing. But I am used to ski season ending. It happens every year. It will come back. It always does.

In the meantime, I have no shortage of things to do. I am not a person who gets bored. I watch very little TV. I have a rich life, two great kids, a wonderful wife. What I do when I have time to do anything is write. I can write all day – I don’t get blocks. Usually the issue is time. But right now I literally cannot do anything but sit here. I can’t even carry a glass of water – I’ll be on crutches for at least three months. My family is being amazing. So you can expect a ramping up of content from The Storm, especially as we get into season-pass release season over these next few weeks.

The surgeon expects a full recovery. I too am optimistic. I wish each of you an excellent and healthy finish to your ski season, to a last run down to a lawnchair tailgate and a cold can of beer from your bro’s cooler and burgers flame-grilled and incinerated from that ravenous joyful hunger that skiing stokes. Hopefully lots of pow days between now and then. In November, I’ll be there to join you.

This week in skiing

I typically append this section to the end of my regular news update, but I’ve had to cut it short or omit it for the past several weeks. So here’s a summary of six of my last seven ski days (the seventh, my last day, is covered above).

Jan. 27 – Holiday Valley and Cockaigne

If geology, not politics, defined our borders, then Holiday Valley would be the eastern anchor of the Midwest, and it would be one of the region’s great ski areas, a pleasant sprawl of 500-ish-foot knolls traced with 11 quad chairlifts. Textbook reality, however, places the ski area on the western edge of the Northeast, a gateway to the far larger mountains popping off the greater Appalachians. Recent snows had filled in the trees and nearly everything between every trail was skiable. Off Yodeler, off Tannenbaum, off Eagle lay expansive glades, marked and thinned. Happy Glade was the best of these, spectacularly rooted in a grove of towering pines.

But the best snow of the day was in the unmarked trees between Shadows and Firecracker off the Chute lift, an untouched foot pillowed between well-spaced trees, the pitch just right for fast explosive turns.

Seated due west down a series of snowy farm roads I found Cockaigne, lost for a decade and now reborn, its pair of 1965 Hall doubles restored in brilliant red. Like Royal Mountain 300 miles to the east, this place doubles as a waystation and activity center for snowmobilers, and all evening their lights drifted through the darkness below like carried lanterns. Cockaigne had won MLK weekend with a 36-inch dump and it was all still there, piled along the edges. There are no skiable glades but I bombed the trails spider-webbed through the unlit forests sprawling either side of the main cut run. Like Sawmill the week before I found nothing but kids and parents skiing with kids and dads skiing in hunting gear because why wouldn’t you? It’s warm. And at this point in my life this may be my favorite kind of ski area.

Jan. 28 – Peek N’ Peak, Mount Pleasant, Tussey

Peek N’ Peak meanders endlessly along a ridge on the far western edge of New York, eight lifts strung exactly parallel up the modest vertical. There is nothing remotely challenging here, but the mountain is interesting and inviting, picturesque with its nouveau Medieval-themed buildings. There are no marked glades but I found good lines skier’s right off King Richard’s, off Sherwood Meadow, and beside Willie Wynkin. The best though was a steep and short wooded plunge wedged between Cross Bow and Long Bow, where I found a foot of untracked dumping out onto Catapult. I also stumbled upon the abandoned runs far skier’s right, ungroomed all-natural-snow trails that were a joy to ski.

Forty-five minutes south is Mount Pleasant of Edinboro, a family-owned knoll with a dairy-barn baselodge and a still-working 1976 Tucker Sno-Cat:

It’s an unassuming place, but, perched southeast of Lake Eerie, one of the snowiest in Pennsylvania. The woods were deep, cut by a tangle of trails favorable to inventive lines. Straightlined through this was an old T-bar line, narrow and thrilling, the towers looming decoratively out of the snow. I skied with GM Andrew Halmi and he told me about lost trails in the woods and the days the place was renamed “Mountain View” and the mountain’s near-bankruptcy and how a pair of local teachers saved the ski area. Eight years ago they replaced an ancient T-bar with a used triple from Granite Peak, Wisconsin. It’s a nice lift for a small ski area, sturdy and modern. While riding up Halmi pointed backward over the chair to successive ridges housing the ghosts of busted ski areas. This place persists and that is an amazing fact.

Three hours east and along toward home I pulled into a packed Tussey, lights rising abruptly into the sky. In the ticket office I presented my Ski Cooper season pass for the promised reciprocal ticket and the guy looked at me like I was trying to pay with a Blockbuster Video card. Eventually he gave me the lift ticket and I rode the old split-pole Borvig quad to the summit (I contacted Ski Cooper, who assured me this was an anomaly and that they had sorted everything out with Tussey’s ticket office). Spectacular views of State College below, the frontside runs legitimately steep and consistent. The main byways had been skied off but the snow on Grizzly was chalky, forgiving, bumpy and empty. I lapped this and then turned east, entering New York over the George Washington Bridge as the weekend blizzard descended.

Jan. 30 – Mount Peter

There exists a contingent of absolutist All-Day-Every-Day Bros who insist that you are not allowed to count a ski day unless you camp out for first chair, ski all day without pause, and fight a 7-year-old for last chair at 3:59 p.m. While I do not have statistics to verify this, I am 1,000 percent certain that none of these bros is in possession of a miniature human. Because those of us who are charged with navigating such cargo through the world understand that the act of piling the small human with layers equal to coats of paint in a 150-year-old dining room, transporting them an hour and 15 minutes to the hill, and escorting them for exactly five runs on the Magic Carpet before driving back home counts as a ski day. And not a relaxed, throwaway day, either. I would rate such an exercise as more mentally and physically challenging than playing a game of Beat the Tram at Jackson Hole or skinning up Mount Kilimanjaro with a refrigerator strapped to your back. So that was my Sunday, though I did sneak in one run (alone) off the Ol’ Pete double before bouncing (my wife watched the kid).

Feb. 1 – Wachusett, Nashoba Valley, Ski Ward

I skied all morning with Jeff Crowley, Wachusett’s part-owner and president, but also, it seems, its mayor. He seemed to know or want to know everybody. He asked if they liked Wachusett, thanked them for coming out, offered directions. He was jovial, approachable, bemused, it seems, that anyone would act in any other manner when their job involved skiing. We toured the whole mountain, and amidst our wanderings Crowley told me this little bit:

We stopped for donuts, met the rest of the family and crew, stood around, took the lift up, filmed a commercial. I showed up to ski, and then suddenly I’m brought, much to my surprise into a commercial. This is what happens when you ski with Jeff Crowley. You become part of the machine – the machine that is widely considered to be one of the best in America at converting lift tickets into dollar bills. On the surface it makes sense: good grooming, high-speed lifts, proximity to population, organized lift lines, fire pits and heated benches everywhere. Drill down and it makes more sense. The place is not a machine. It’s a cyborg, a fluid and evermoving construct distilled to assembly-line perfection, but powered by a human heart.

Nashoba Valley sits half an hour away, a piney bump rising 240 vertical feet like a built thing off of the subdivisions surrounding it. In the sunshine I cruised fast laps off the summit, where four chairlifts meet from four different directions. Massachusetts had gotten absolutely caked over the previous weekend, feet of snow. No refreeze yet so coverage and conditions remained outstanding. Nashoba is small, but well-placed trees fence the piste into a trail network, winding sometimes, my favorite the fast and tight Lobo, a superhero accelerator that pops you out on a fast runout back to the Chief chair. It was nearly 4:00 and the after-school crowd had materialized, racers and park rats and onsie-stuffed littles starfishing their way down the amazing array of ropetows and carpets Nashoba has arranged at the base.

Ski Ward, 25 miles southwest, makes Nashoba Valley look like Aspen. A single triple-chair rising 220 vertical feet. A T-bar beside that. Some beginner surface lifts lower down. Off the top three narrow trails that are steep for approximately six feet before leveling off for the run-out back to the base. It was no mystery why I was the only person over the age of 14 skiing that evening.

Normally my posture at such community- and kid-oriented bumps is to trip all over myself to say every possible nice thing about its atmosphere and mission and miraculous existence in the maw of the EpKonasonics. But this place was awful. Like truly unpleasant. My first indication that I had entered a place of ingrained dysfunction was when I lifted the safety bar on the triple chair somewhere between the final tower and the exit ramp and the liftie came bursting out of his shack like he’d just caught me trying to steal his chickens. “The sign is there,” he screamed, pointing frantically at the “raise bar here” sign jutting up below the top station just shy of unload. At first I didn’t realize he was talking to me and so I ignored him and this offended him to the point where he – and this actually happened – stopped the chairlift and told me to come back up the ramp so he could show me the sign. I declined the opportunity and skied off and away and for the rest of the evening I waited until I was exactly above his precious sign before raising the safety bar.

All night, though, I saw this bullshit. Large, aggressive, angry men screaming – screaming – at children for this or that safety-bar violation. The top liftie laid off me once he realized I was a grown man, but it was too late. Ski Ward has a profoundly broken customer-service culture, built on bullying little kids on the pretext of lift safety. Someone needs to fix this. Now.

Look, I am not anti-lift bar. I put it down every time, unless I am out West and riding with some version of Studly Bro who is simply too fucking cool for such nonsense. But that was literally my 403rd chairlift ride of the season and my 2,418th since I began tracking ski stats on my Slopes app in 2018. Never have I been lectured over the timing of my safety-bar raise. So I was surprised. But if Ski Ward really wants to run their chairlifts with the rulebook specificity of a Major League Baseball game, all they have to do is say, “Excuse me, Sir, can you please wait to get to the sign before raising your bar next time?” That would have worked just as well, and would have saved them this flame job. For a place that caters to children, they need to do much, much better.

Feb. 6 – Mount Peter

At Mount Peter we left 5-year-old Logan with an instructor and skied the glimmering icy world all around us. The storm that had dumped up to two feet of snow up the Vermont Spine and other points north had plastered southern ski areas with half an inch of ice:

We took a half dozen runs and that was enough. Logan is able to ski without falling now and so my goal each week is to exit before he begins hating it.

Feb. 10 – Cranmore and Shawnee Peak

It’s that rare thing in the east, a ski area rising from town, like a mini-Aspen or Park City airlifted over the plains. But that’s Cranmore – it’s right there, 1,200 vertical feet lurching above the neighborhood like it’s just someone’s extra-big backyard. The East needs more of this, but at least it has some of it. Ka-boom. And they’d gotten hit with an extra six to eight, too, just a few days before. Unfortunately the refreeze beat me to the woods, so I spent the morning lapping fast groomers off all sides of the summit. A low-traffic day, nearly everyone on the hill a racer, squeezed onto a single run. The groomer marks were only half tracked-off by the time I left at noon, every trail skied, an easy task with that high-speed Skimobile banger shuffling me up the incline over and over.

Soft turns at Shawnee Peak. Rain sometimes. I skied with GM Ralph Lewis, who had worked for Boyne at Loon and left to take the top job here and now finds himself at Boyne once again. On the triple chair ride to the summit I turned and saw Moose Pond below and gasped. It’s striking.

We skied every trail except the closed ones leading down to Sunnyside. It’s an excellent hill. Approachable. Comfortable. The trails follow the mountain. I scouted room for more glades, imagined the possible terrain expansion skier’s left of the summit. The place needs newer lifts, a bigger lodge, more parking. But the bones are good. Boyne got themselves a win with Shawnee Peak, and they know it.

Nice write-up! A shame it had to happen, especially with all those other trips you were planning, but thank goodness you'll be back next year.

LOL, not quite as bad, but the same thing happened to me at Ski Ward when I visited for the first time a year ago! First ride and I put the bar up at the last tower. Four seconds later I hear a loud raspy voice to my left 'use that safety bar!' I turned to see that I had come in sight of the ski patrol shack and the guy sitting in a chair in front was not happy with me. After that I made sure to wait until after the sign. I didn't see it happen to many or any other people, but it was a Monday so maybe it was mostly locals who knew the drill by then. It wasn't enough to ruin the ski day, but if they had humiliated me like they did to you it definitely would have.

So sorry to hear about your leg!! Classic skier injury— maybe you can consider it a sort of badge of accomplishment or belonging?? Ha! I loved your line about “the entire episode is exhibit A for the value of experienced leadership at ski resorts, of valuing these people more than the $5 million lifts that cart your skiers up the mountain.” As someone who works in the industry but is still relatively new, I can attest first-hand to how accurate this is. The people are incredible and work so hard (for pretty low pay) to create access and opportunities for people to experience this amazing sport, and to enjoy it (and feel safe)! We have lots of work to do to get even more people out there, for sure, and I hope we can broaden our reach to engage even more folks in this wonderful opportunity to enjoy the outdoors in the winter. It’s the best!!