Five Charts Explaining America’s Aging Lift Fleet

Operators ponder how to replace aging machines as new lift prices skyrocket and the supply of easy-to-relocate fixed-grip lifts dries up

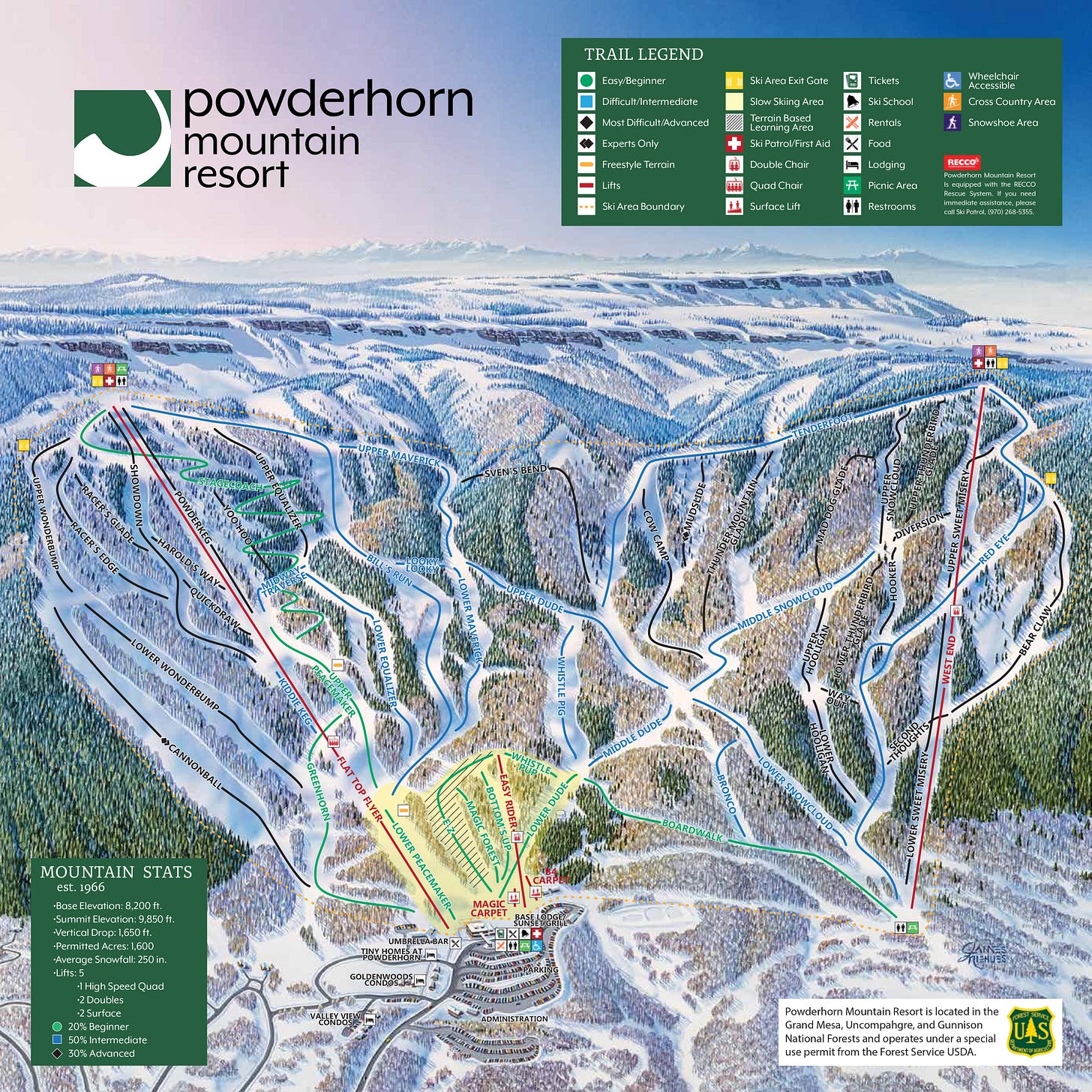

Powderhorn, Colorado’s West End double chair is a strange and incredible machine. A 1972 Heron-Poma double chair rising 1,655 vertical feet, it is, at 7,000 linear feet, the second-longest fixed-grip chairlift still spinning in America.

The ride is low and slow, 15 minutes and 50 years long, a time machine with no restraint bars, tensioned at its base by a visible counterweight, at once an industrial relic and a working monument to machine durability. In a high-tech Colorado laced with 118 high-speed chairlifts, West End delivers riders to a simpler, rapidly disappearing version of skiing.

The hardy and the hardcore relish this minimalist experience. Or say they do. Skier traffic patterns, resort officials say, reflect a different reality. Powderhorn’s 1,600 acres are neatly split into two peaks, each served by a chairlift of roughly equal length and height. West End’s counterpart is Flat Top Flyer, a 1,612-vertical-foot high-speed quad that runs bottom-to-top in six minutes.

“Most skiers take a couple laps on West End and head back over to the Flyer,” Powderhorn General Manager Ryan Schramm told me.

That dynamic may change dramatically next year. Powderhorn, working with lift giant Leitner-Poma, plans to demolish West End and replace it with a high-speed quad relocated from Snowmass, Colorado, which removed its 1995 Elk Camp machine this past summer to make way for a new six-pack on the same line. Powderhorn will name the new-used machine “Wild West Express.” As with most relocated detachables, the lift will re-use steel components like carriers and towers, but will replace just about anything mechanical or electronic. The approach should save Powderhorn $2 to $3 million, resort officials tell me, and will, to the average skier, look and feel like a new chairlift.

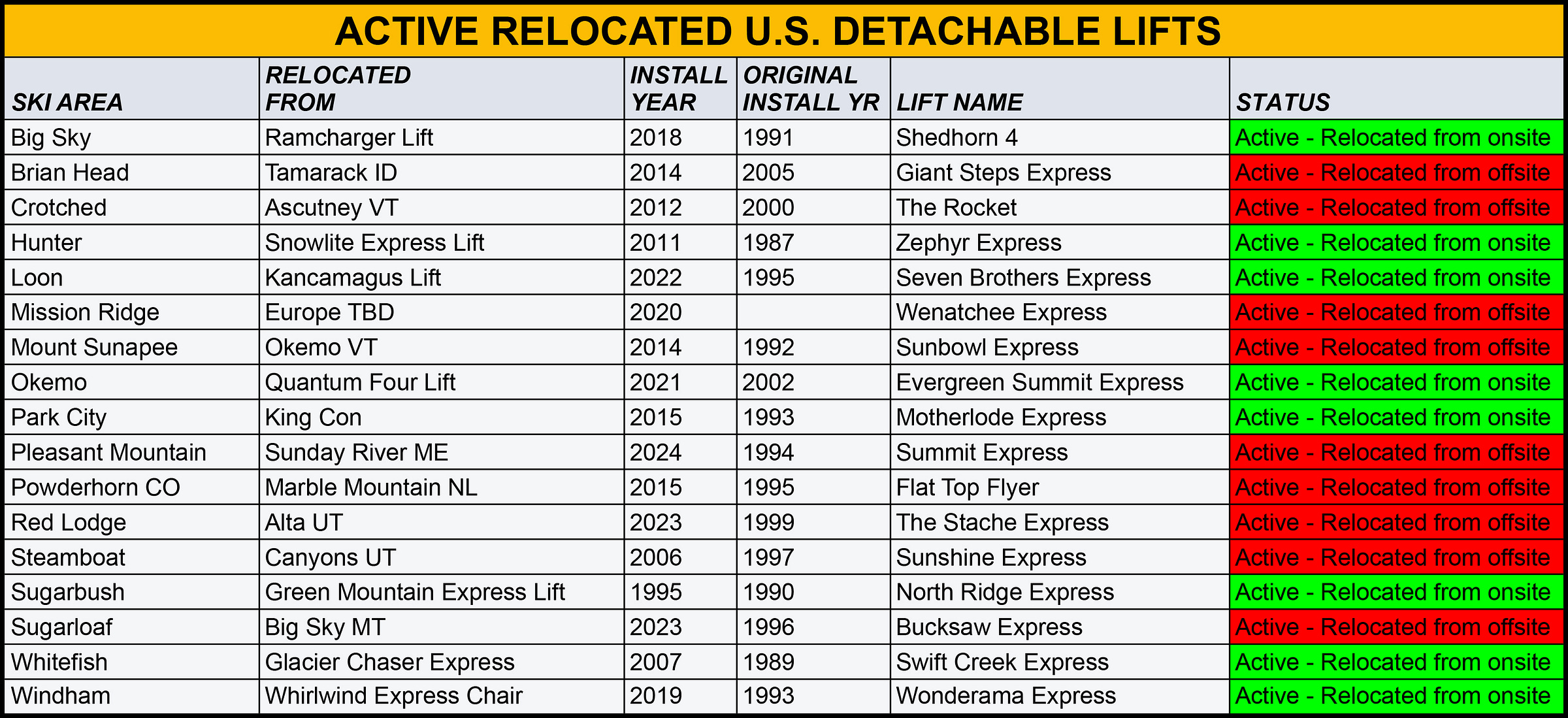

The Wild West lift didn’t strike me, at first, as a novel project. Moving chairlifts from one ski area to another is common - around 14 percent (264) of America’s 1,952 operating chairlifts began life elsewhere. But high-speed lifts represent just a small percentage of these relocations: only nine of America’s 501 active detachable lifts have been moved to their present resorts from a different ski area (Wild West Express would be the tenth). Another eight detaches have been repurposed at their original ski areas. These low numbers are strange for one reason: the first detachable chairlift debuted at Breckenridge in 1981, and high-speed quads and six-packs long ago became the preferred workhorse for large ski areas. Why, given how common these lifts have become, have so few of them found a second life, even as larger operators such as Aspen, Vail Resorts, and Alterra steadily retired first-generation machines for new ones?

Detachable chairlifts, it turns out, have not proven as durable as their fixed-grip ancestors. The grips that detach and reattach to the haulrope at load and unload stations are expensive and wear out quickly. The machines themselves are large, complicated, and challenging to move. Re-installing any lift, but especially a detachable lift, is more complex than building a new one, multiple resort officials and engineers familiar with the process say, but it is also less expensive. For both of those reasons, the major lift manufacturers, multiple operators say, strongly discourage such relocations.

That hesitation complicates a delicate historical moment for American skiing. Hundreds of chairlifts built in the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, many by companies that no longer exist, are reaching the end of their useable lives. The proliferation of hard-to-move detachable lifts, whose fixed-grip ancestors often found new homes at smaller mountains, has left fewer viable relocation candidates. For decades, scrappy independent outfits such as Pats Peak, New Hampshire and Great Divide, Montana have expanded and modernized by aggressively seeking out and reinstalling decommissioned chairlifts from ski areas across the continent. But the viability of this model is fading, operators tell me, as a shrinking inventory of re-usable lifts corresponds with skyrocketing chairlift prices over the past decade (exact cost figures are largely undisclosed, and each lift is unique, but anecdotal evidence suggests that prices have approximately doubled since the years immediately prior to Covid).

This harsh market dynamic is already impacting smaller ski areas. Whaleback and Tenney, New Hampshire and Loup Loup, Washington all had to shutter the bulk of their terrain when their summit chairlifts failed last winter. Hesperus, Colorado has sat idle since 2023, when its only chairlift failed. Riblet, which manufactured this double chair, folded in 2003. While Riblet lifts are famously durable - 221 still spin across the United States - parts are growing scarce, qualified mechanics are steadily retiring, and machines don’t last forever. Hesperus’ double arrived used in 1988 from Mount Bachelor, where it likely started spinning in the early 1960s.

Technology and infrastructure have long acted as a sorting mechanism for skiing’s long-term survivors. The wipeout of hundreds of ski areas from the 1970s through ‘90s largely spared those operators who invested early and often in snowmaking. But one crucial attribute of Hesperus and Powderhorn suggests that modernizing America’s sprawling and aging lift fleet is already proving more challenging than adding snowmaking: both are owned by larger parent companies. Park City-based Pacific Group Resorts (PGRI) has run Powderhorn since 2018, and operates five additional ski areas. Durango-based Mountain Capital Partners (MCP), which operates more than a dozen ski areas in the U.S. and Chile, purchased Hesperus in 2016. In theory, both companies should have the resources to outfit their mountains with new lifts, even at current prices: MCP is in the process of purchasing four Chilean ski areas, and PGRI bought out the company’s longtime Powderhorn co-owners earlier this year.

But officials from both companies say that each of their ski areas must be a sustainable business on its own. Neither generates enough revenue to (likely) ever pay off a new chairlift at current prices while still tending to other capital needs, they say.

Ever since Powderhorn announced the Wild West project last month, I’ve been talking to folks across the industry, trying to better understand the state of America’s lift fleet, and to determine whether there’s a blueprint to modernize these machines without bankrupting smaller operators. Is Wild West an anomaly, or a template? What happens when the supply of used fixed-grip lifts finally dries up? Why are new lifts suddenly so expensive and people qualified to repair them so scarce? How much do operators actually save by moving a used lift? How much of a used lift is actually used? What is the formula deployed so effectively by Boyne Resorts, which has relocated four detachables within its system since 2018 and has plans for a fifth? What does it take, logistics- and engineering-wise, to remove a chairlift, transport it across the country, and reinstall it on a mountain that it wasn’t designed for? Are we forever stuck with (essentially) two American lift manufacturers? If there actually is both an aging-machine and affordability crisis, then how have U.S. operators managed to install nearly as many lifts in the first half of this decade (245) as they did in all of the 2010s (287)? Why do so many large operators scrap their old machines rather than resell them to smaller ski areas? And why do other big operators – like Deer Valley, which has relocated more chairlifts to other ski areas than any resort in America – so intentionally do the opposite?

I emerged from these conversations with a blend of concern and optimism. Yes, we’re still riding 136 chairlifts built in the 1960s, and at some point, they’ll have to make way for something else. But ski area operators have always been inventive, resourceful, and resilient, and small mountains are modernizing through inventive means.

These conversations, along with research compiled from Lift Blog and other sources, will inform a series of stories on the state of America’s lift fleet over the coming months. For today, let’s start with a holistic picture of just how old that lift fleet is.