Boyne Resorts Launches Unlimited-Access, Portfolio-Wide Pass for 2025-26 Winter

Pass includes unlimited access to Big Sky, Brighton, Summit at Snoqualmie, Cypress, Boyne Mountain, Highlands, Sunday River, Sugarloaf, Pleasant Mountain, & Loon

Here’s a project for you, aspiring MBAs: how did Boyne make it through? Not every transnational ski company failed, but many of them – perhaps most of them – did. S-K-I and American Skiing Company and Intrawest, at one time dominant, owners of grand properties of the Whistler and Steamboat and Killington sort, collapsed or faded. Boyne, Michigan-based, launched from a 500-vertical-foot glacial ridge that no one other than Everett Kircher thought could be a ski area, did not seem a match for any of these swaggering collectives, with their stock exchange listings and big-mountain HQs and brash marketing. But Boyne started in 1948, grew slowly, and outlasted just about everyone. Only Aspen Skiing Company, which dates to 1947, owns a longer legacy among multimountain U.S. operators.

Today, Boyne manages the third-most U.S. ski areas of any operator, behind Vail’s 36 and Alterra’s 17. And yet, “Boyne doesn’t get much attention or respect,” the late Chris Diamond wrote in Ski Inc. 2020 (a must-read for any fan of this newsletter). “Despite its scale and geographic diversity, Boyne continues to be pigeon-holed by skiers (and even the industry) as a Midwest regional player.”

Diamond lays out an extended case for Boyne’s resiliency: an institutional obsession with snowmaking and advanced chairlifts, geographic diversity to offset down winters, expansion into year-round operations, and building diverse terrain and on-site bed bases. But Boyne’s failed competitors built around these same principles. Boyne’s most compelling secret weapon may be the Gatlinburg Sky Park, a Tennessee sightseeing chairlift/printing press parked in the dead-ass center of a gaudy and improbable tourist town that materializes out of Smokey Mountain National Park like an acid trip.

But I will toss out one more theory that Diamond neglects to mention – one that I will admit is entirely anecdotal and possibly mis-remembered: growing up in Michigan, Boyne, with its two big ski areas, was synonymous with skiing, the aspirational peak of regional winter. And Big Sky, because Boyne owned it and because Boyne passholders could ski there for free, was synonymous, in Michigan, with western skiing. Everyone who had skied out West, it seemed, had skied at Big Sky, even though Colorado was closer, more famous, and easier to get to. Colorado’s resorts were also much larger – at least until Big Sky ran the tram up Lone Peak in 1995. But by creating a direct pipeline from a populous (9 to 10 million people) and cold state with small ski areas to a glorious aspirational ski resort capped by the most dramatic summit in U.S. skiing, Boyne was a perhaps accidental pioneer of the hub-and-spoke pass model that now defines the American ski industry.

And yet, Boyne has never sold a companywide pass. At least not anything branded as such. Most of the company’s top-tier unlimited passes include three days at each of Boyne’s other ski areas, and Boyne joined the Ikon Pass (and M.A.X. Pass before it), from the outset. “We are a company of resorts, rather than a resort company,” Boyne officials often tell me.

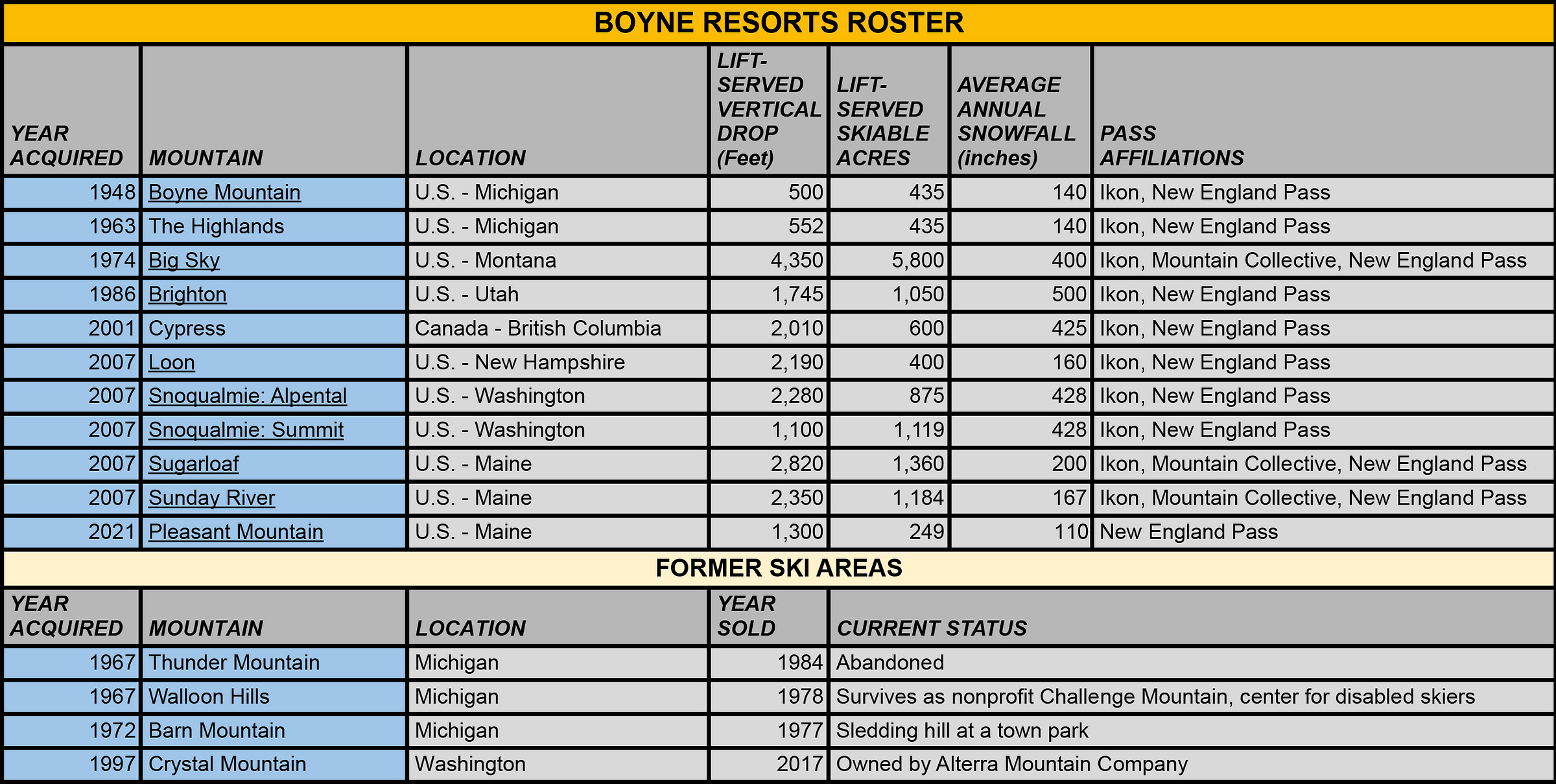

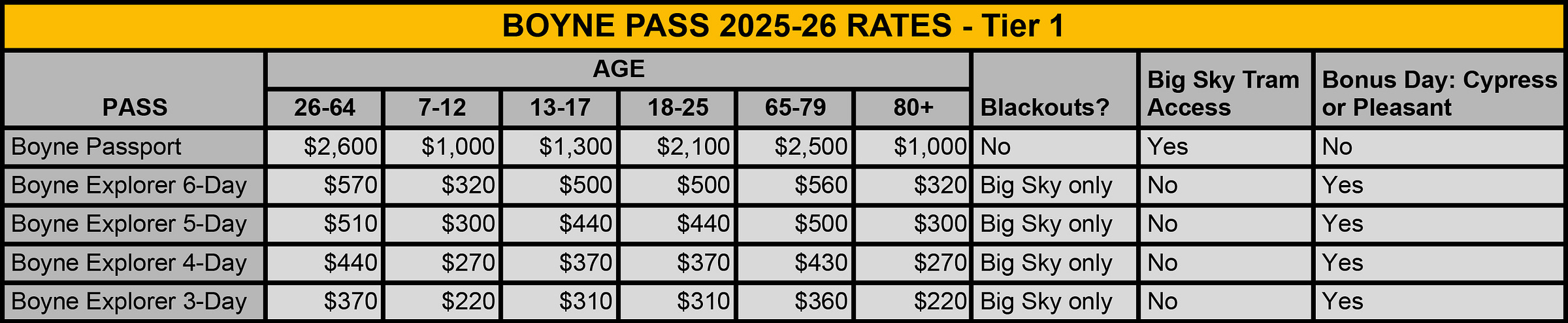

That posture changes today, as Boyne Resorts rolls out two versions of a portfolio-wide pass good at all 11 of its ski areas: an unlimited-access-to-everything version and a three- to six-day (total) product that nixes Big Sky tram access and blacks the Montana mountain out on holidays, but includes one bonus day to be deployed at Pleasant or Cypress:

It’s worth noting that the Passport includes early lift access at Big Sky, Sunday River, Sugarloaf, Boyne Mountain, and Highlands.

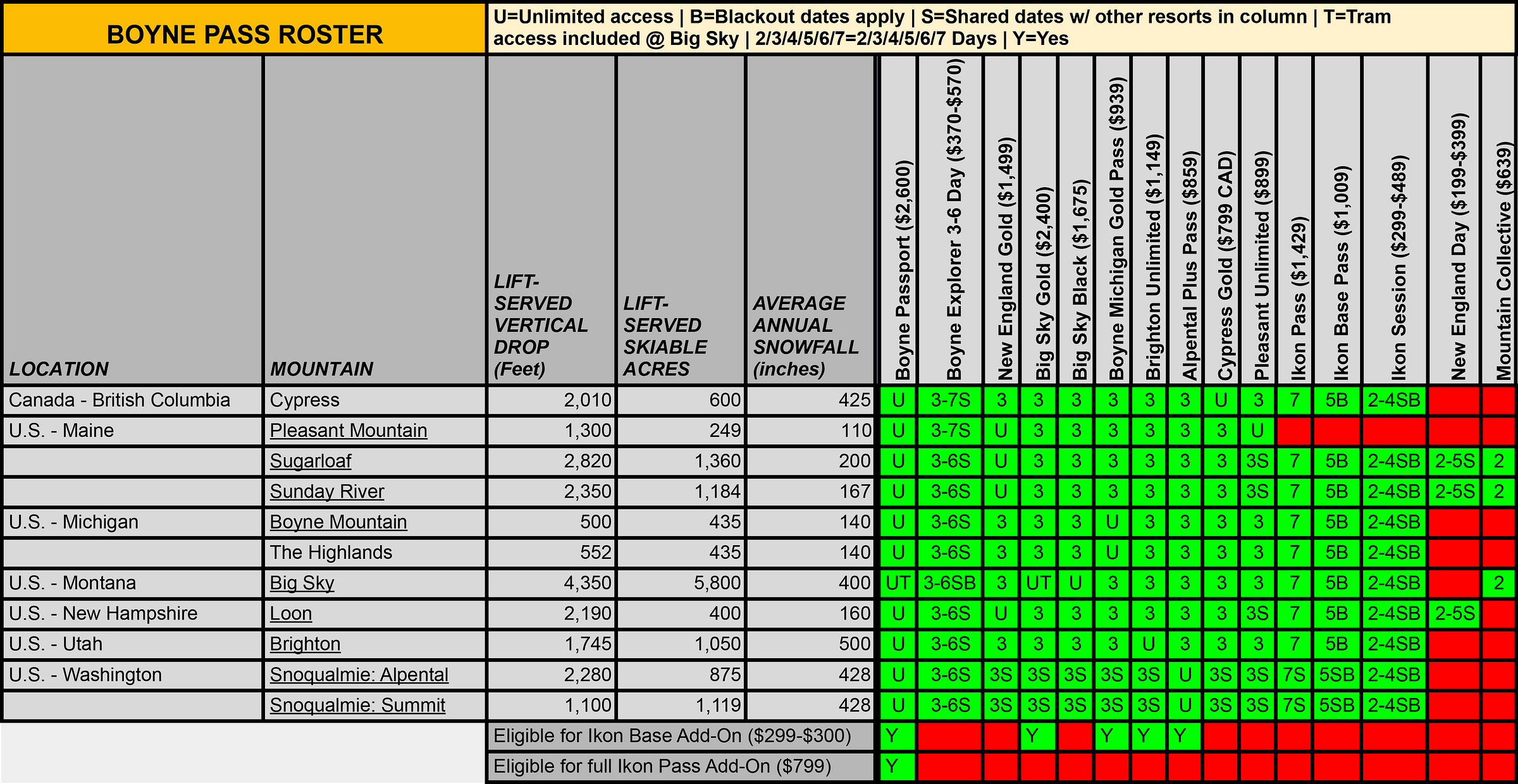

Here’s how the two tiers stack up against other products that provide access to multiple Boyne ski areas, including the company’s various top-tier passes, the Ikon Pass, and the Mountain Collective:

At top rates more than double that of the Epic Pass, the Boyne Passport does not appear to be positioned as a mass-market product. Nor is it a signal that Boyne is fracturing from Ikon. The company remains “committed and proud to be a partner of the Ikon Pass long term,” Boyne Resorts Chief Marketing Officer Nick Lambert assured me. And passholders can combine the products, adding an Ikon Base on for $299 or – a first for any Boyne pass product – a full Ikon Pass for $799.

The catalyst for the Boyne Passport appears to be two-fold, according to Lambert: to create a convenience product for a small but avid group of skiers who already migrate between Big Sky and Boyne’s regional hubs throughout the winter, and a companywide synching of RFID technology that streamlines resort-to-resort movement.

The Explorer Pass, with its lower pricepoints and more limited commitment, has more potential as a mainstream ski pass that can compete directly with Epic Day and Ikon Session.

Here’s a deeper look at Boyne’s new pass products, and what they mean for the company’s skiers, its ski areas, and the multimountain ski pass market at large: