5 Lessons From 1990s Ski Magazines That Taught Me How to Shred

Because broke people need to learn too

I met skiing like a lawnchair meets a tornado, flung and cartwheeled and disoriented and smashed to pieces. I was 14 with the coordination and dexterity of a lamppost. The mountain was merciless in its certainty of what to do with me. It hurt.

I tried again and was met like an invader at the Temple of Doom, each run a stone-rope-and-pulley puzzle I could not solve – a puzzle that invariably ended with me smashed beneath a rock.

When two years later I tried a third time I had grown into my body and could without turning or otherwise controlling myself descend the modest hill on most runs intact. The following Christmas I asked for skis and got them and the fabulous snowy north unrolled with purpose and mission before me.

Now I just had to learn how to ski.

This was a bigger problem than it sounds like. No one in my family skied. None of my friends knew how to ski either – at least not well enough to show me how to do it. Lessons were not happening. If you think a 17-year-old who makes $4.50 an hour bagging groceries is going to spend the equivalent of a week’s pay on what is essentially school on snow when school is not in session, then you have either never met a 17-year-old or have never been one. As it was, I could barely afford the lift tickets and gas to get me to the hill.

What I could afford was ski magazines. And ski magazines in the nineties were glorious things, hundreds of pages long and stacked with movie reviews and resort news and adrenaline-laced 14-page feature stories.

And there was ski instruction. Pages and pages of it in nearly every issue.

This seems arcane now. Why not just watch a video? But this was the mid-nineties. There was no YouTube. Hell, there was barely an internet, and only the computer-savviest among us had the remotest idea how to access it.

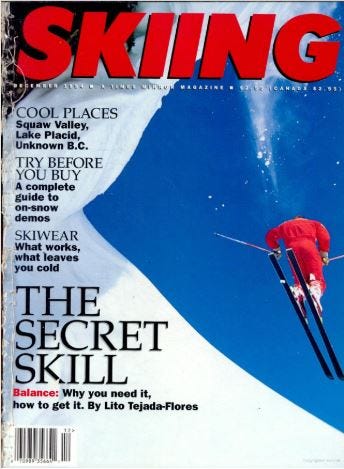

My first ski magazine was the December 1994 issue of Skiing. It cost $2.50 and it looked like this:

The volume of ski instruction in just this one issue is staggering. A nearly-5,000 word piece by venerable ski writer Lito Tejada-Flores anchored a 19-page (!) spread on the art and importance of balance, which was in turn prefaced by a separate front-of-the-mag editorial outlining the whole package. An additional eight pages of ski instruction tiered from solid-green beginner to expert complemented this. And all this in an issue that also included a 13-page high-energy feature on roaming interior BC and 10-page write-ups of Squaw Valley and Whiteface.

Each month I bought Skiing, and most months I also bought Ski and Snow Country. I also bought Powder but even then Powder could not be bothered with ski instruction. The instruction wasn’t the first thing I read but I always read it and I usually read it many times.

This was a process. Ski instruction articles are often dense and deliberate and usually anchored to numbered photographs or drawings demonstrating movements and technique. Think of it as drill instruction in extreme slow motion. It wasn’t all useful but what was useful became essential.

I doubt anyone knows how to write about ski instruction with this kind of clarity and detail anymore, just like no one knows how to build a covered wagon anymore – it is a lost art because it is now an unnecessary one.

But this is how I learned how to ski. And because this is how I learned and because I re-read each of the pieces that resonated with me so many times, this written instruction formed the indelible framework around which I still think about skiing.

So here, in no order of importance, are five particularly memorable excerpts from my 1990s ski education. All of these happen to come from Skiing, which also happens to no longer exist. Consider this a tribute to that magazine’s one-time greatness, and the influence it had on at least one skier:

1) Face the Goddamned Fall Line

Be a Ranger, Face the Danger – Jerry Thoreson, Skiing, January 1996

The more I ski, the more I realize that the simplest, most basic skills are the most important. One of these is simply to face the direction you intend to go – specifically, where you plan to finish your next turn. That means looking downhill, keeping your body facing the fall line, facing the danger.

This is the number one mistake I see otherwise accomplished skiers make – the kind that swoop gracefully and like some kind of antique wind-up toy anchored to a track down groomed boulevards, but flail in the bumps or trees. Countless articles mention some variation of this advice, but the point is that no matter what is happening to your skis, your upper body needs to be facing downhill at all times. If you don’t do this, you’re gonna have a bad time.

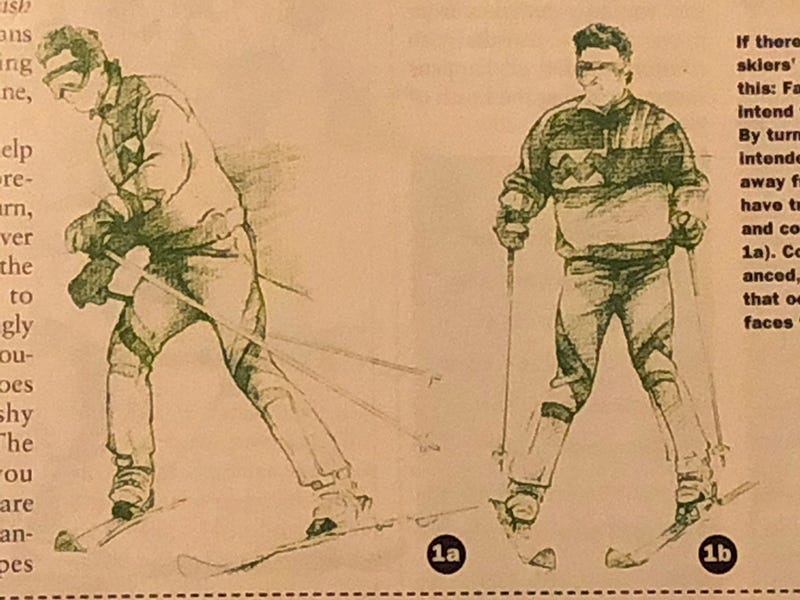

Figure 1a shows a skier facing away from where he intends to finish his next turn. His weight is on his inside (right) ski, and his outside (left) leg is straight and stiff – making it difficult for him to turn his skis and maintain the control he needs. This skier is not having fun.

Compare that with Figure 1b. Here the skier is looking where he wants to finish his next turn. He is facing the danger. He looks comfortable, his stance is upright, and his balance is on the center of his outside ski, allowing him to maintain control. He is having fun.

Put away your smartphones and your GoPro machines, Kids. All you need to have fun on the slopes is proper body positioning.

Thoreson leaves us with these tips:

- Remember to not only look toward the finish of your next turn, but to face your body that way, too.

- Pick something below you to use as a target. Face that target as you ski, and stop just above it.

2) Know How to Use Your Poles

Different Pole Actions for Different Turns– Scott Mathers, Skiing, February 1995

One of the most shocking things that I often hear even experienced skiers say is that they consider poles useless. And from close observations carried out via chairlift over the decades, I would say that roughly 80 to 90 percent of skiers haven’t the slightest idea why they’re carrying around twin three- to four-foot-long sticks. If they use them at all, it’s to push themselves along on a traverse.

But learning to use my poles was one of the most useful and essential elements of becoming a complete skier. Mathers:

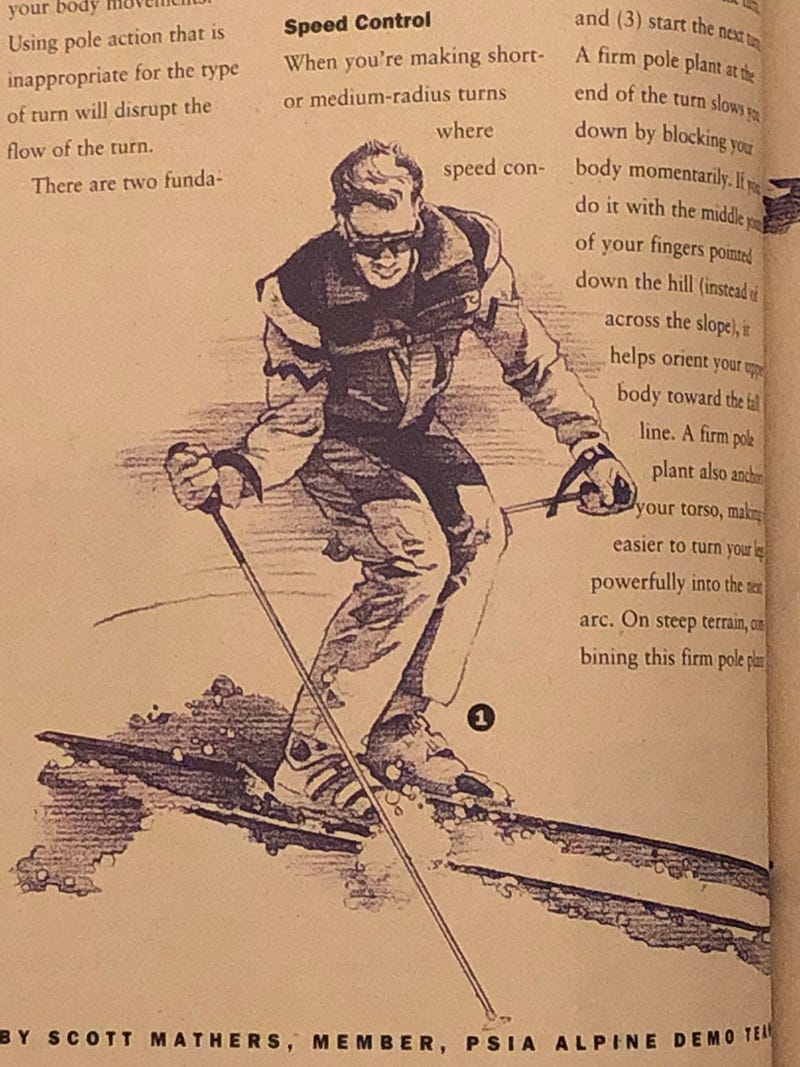

In expert skiing, the timing and intensity of your pole action – both the pole swing and the pole plant – should complement the rhythm and direction of your body movements. Using pole action that is inappropriate for the type of turn will disrupt the flow of the turn.

There are two fundamentally different types of pole action: (1) using the pole for braking and speed control and (2) using the pole to enhance gliding and maintain speed.

Speed Control

When you’re making short- or medium-radius turns where speed control is important (such as on steep terrain and in bumps), plant your pole firmly as you finish the turn. The three parts of the action are (1) swing, (2) plant as you end the turn, and (3) start the next turn. A firm pole plant at the end of the turn slows you down by blocking your body momentarily. If you do it with the middle joints of your fingers pointed down the hill (instead of across the slope), it helps orient your upper body toward the fall line. A firm pole plant also anchors your torso, making it easier to turn your legs powerfully into the next arc. On steep terrain, combining this firm pole plant with a powerful edge set gives you security and a feeling of confidence.

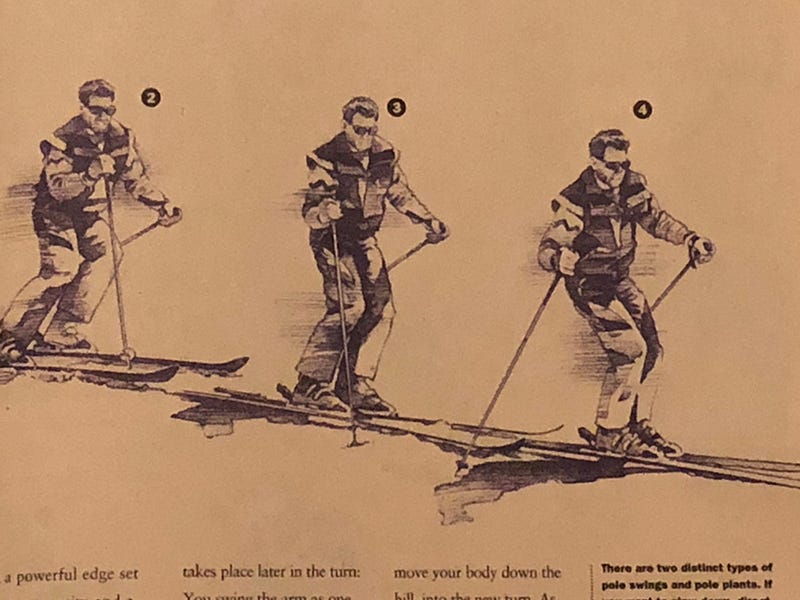

Speed Maintenance

In long-radius turns on flatter terrain, where you wish to glide smoothly from turn to turn and maintain your speed, the pole action is smoother and gentler, and takes place later in the turn: You swing the arm as one turn is ending and touch the pole tip lightly in the transition between turns. The three parts of the action are (1) swing the pole, (2) move your body toward the next turn, and (3) touch the snow with your pole tip. Use the smooth pole swing to help move your body down the hill, into the new turn. As you change edges, lightly touch your pole tip to the snow and keep your hand moving in the direction of the new turn. This kind of pole action helps link your turns, aid your balance, and provide sensory feedback regarding the pitch of the slope.

In other words: unless you’re a 3-year-old S-turning across the carpet greens in a ski school pack or a rad-to-the-max park kid who’s too cool for a jacket let alone poles cause they might interfere with his Spotify Brah, learn how to use your poles, for your own good.

3) Always Be Turning

The Balancing Act – Lito Tejada-Flores, Skiing, December 1994

Sometimes skiing becomes so exciting, so continually challenging, that you feel you’re skiing in something like crisis mode. You have trouble stringing two or three turns together, much less a whole run. Yet top skiers slice right down through those gnarly bumps, through that cut-up crud and lousy snow, through those nearly impossible transitions. And they appear to be rock steady, perfectly in balance the whole time.

What’s their secret? I’m really going to let the cat out of the bag here. Good skiers, great skiers, don’t ever feel as poised and well balanced as they look. The skiers you admire in these tough situations are out of balance often, almost continually – that’s what rough-terrain, rough-snow skiing is all about. But they are also continually rebalancing themselves, getting back on top of their feet and skis before things get out of hand.

The basic mechanism for continual rebalancing is to keep linking your turns, constantly [emphasis mine]. Whenever you start to lose it in one turn, plant your pole and start a new turn, without thinking, without hesitation, above all without asking yourself whether you are ready, and in balance, to start that turn. You can always trick yourself into decisively starting the next turn by simply reaching downhill for it with your new pole. Reaching downhill with your pole tends to keep your body moving downhill, too, making that commitment we just talked about an automatic happening, not a conscious decision.

In other words, Always Be Turning. This simple mantra has saved my ass in every kind of condition, on every kind of slope, on every single day I have ever skied. Whenever I catch an edge or get knocked back in the bumps or have to dogleg around a surprise log in the trees, no matter how wildly I’m flailing, I just reach and start the next turn. It’s never not worked.

4) “The only bumps you need to see are those lined up right below you”

Raw Aggression– Kristen Ulmer, Skiing, February 1995

Skiing bumps is hard. Learning to ski them can seem impossible. This two-page primer by freeskier and all-around badass Kristen Ulmer is the best article on the subject I’ve ever read, and I must have read it 100 times.

Along with a lot of screaming ‘90s gnar aggression and attitude, Ulmer embeds a few bump-skiing fundamentals that I still think about whenever I’m about to drop into a mogul field as broad as Manhattan. Among them:

Loosen your knees

...ski onto a single mogul and let your legs bend and absorb the bump. As soon as your legs absorb the bump, immediately start a turn and press your hips forward (be careful not to lean back with your upper body as you do so). At the same time, press your ski tips down to maintain contact with the downhill side of the bump.

“Face the fall line!” (yes, this again)

Most novice and intermediate skiers turn their skis and upper body too far away from the fall line, toward the side of the slope. This is traversing bumps, not skiing them. Try this: On a gentle slope, grip your ski poles as if they were swords and point the tips at a stationary object you see at the bottom of the run. As you ski, keep pointing your pole tips and your chest toward that object. Make your turns with your lower body; use your upper body as a pointing device.

“Shin pressure against the boot tongue at all times is mandatory”

You should feel your knees constantly driving forward and the shovels of your skis working equally as hard as the tails. By consciously putting pressure against your boot tongues before you push off to start a mogul run, and by maintaining that pressure throughout the run, you’ll find that staying forward will become an unconscious habit.

“In the moguls, without perfectly positioned hands and hard-working legs, you’ll get thrown for a loop”

Practice on groomed slopes, making short turns in which only your lower body moves side to side. Your head moves straight as a string down the fall line. Your hands are in front. The only motion allowed is the flicking of your wrists to plant the poles. Anything more dramatic than that will kill you in the bumps.

“Look at least three bumps ahead”

If you see the next mogul coming, you’re looking at your feet… It’s easy to be overwhelmed by an entire mogul field. But the only bumps you need to see are those lined up right below you. So concentrate on those and block out the rest.

It took me 50 days over two full seasons before I could string together a complete bump run, and I credit this article 100 percent with why I was able to ever do it at all. And it was worth it. Once you know how to rip a bump line, it’s something you never, ever get tired of.

Ulmer still runs camps and I still can’t afford them. But if I ever see her or speak with her, I will thank her for making me a bumper for life.

5) Only look at the trees you want to run into

Seize The Trees– Bill Kerig, Skiing, March/April 1995

If there are glades open and the snow is good, I won’t ski anywhere else. The trees have the fewest people, the most interesting lines, the most intimate connection with the mountain in its raw state (if that raw state included a clan of helpful beavers that chewed out the underbrush each summer). As Ulmer became my bump guru, Kerig, in this article published the following month, became my teacher in the trees. Aside from the obvious tips to wear goggles and undo your pole straps, Kerig offers these helpful bits of instruction:

Steer through the trees

There are two ways to turn a ski – carving and steering. Carving means putting the ski on edge and weighting it. … In tight trees, it’s best to steer more than carve. … In trees, you’ll need to change direction quickly, and unless you’re a master of carving, you’ll probably not be quick enough. Steer with your knees and feet, while keeping your upper body upright and facing straight down the hill (similar to a mogul skiing position). You may find yourself wanting to counterrotate your upper body (turn it in the opposite direction that your skis are turning) but try to stay away from this, as it often leaves you with all your weight on your uphill edge and can cause cartwheeling.

Don’t look at the trees, Dummy

Gaps, of course, are the key. You want to move into them as they open for you. Look for the spaces, not at the trees. … Also, as in good mogul skiing, you must look down the hill, past the next open space to the one after that. You don’t need to look at what you’re skiing. A combination of your peripheral vision and your body’s ability to react will take care of what’s underfoot. Keep your eyes down the hill and you’ll move through far smoother.

Hands up!

Keep your hands held high between pole plants – a very good idea for two reasons: Exaggerating the upward motion of a pole plant helps to unweight the skis and allows for a bit of float in the end of the turn (an old powder ploy), and keeping your hands up will also help protect your face from unfriendly branches or angry squirrels.

Maybe somewhere, someone is still etching beautifully sculpted writing minutely describing the art of learning to ski. It’s been a long time since I was proactively seeking advice, though, and my assumption is that most of this learn-to-ski business has drifted over to YouTube and similar video outlets.

I happen to still be in possession of my original copies of the issues quoted above. For those who want to see the originals in all their ad-riddled glory, it looks as though Google Books has archived most or all of Skiing’s back issues, though Googling “Skiing magazine” to track down specific issues is about as helpful as trying to locate the Titanic by saying that it sunk “in the water.” But for those willing to track it down, this stuff is still out there, waiting for all of skiing’s aspiring covered-wagon makers.

The Storm Skiing Podcast is on iTunes, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, TuneIn, and Pocket Casts. The Storm Skiing Journal publishes podcasts and other editorial content throughout the ski season. To receive new posts as soon as they are published, sign up for The Storm Skiing Journal Newsletter at skiing.substack.com. Follow The Storm Skiing Journal on Facebook and Twitter.

Check out previous podcasts: Killington & Pico GM Mike Solimano | Plattekill owners Danielle and Laszlo Vajtay | New England Lost Ski Areas Project Founder Jeremy Davis | Magic Mountain President Geoff Hatheway | Lift Blog Founder Peter Landsman | Boyne Resorts CEO Stephen Kircher | Burke Mountain GM Kevin Mack | Liftopia CEO Evan Reece | Berkshire East & Catamount Owner & GM Jon Schaefer| Vermont Ski + Ride and Vermont Sports Co-Publisher & Editor Lisa Lynn|